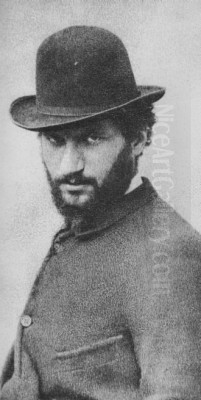

Emilio Longoni (1859-1932) stands as a pivotal figure in late 19th and early 20th-century Italian art. An ardent proponent of Divisionism, Longoni's oeuvre is characterized by its luminous portrayal of Alpine landscapes, poignant social commentary, and a profound engagement with the optical theories of color. His journey from humble beginnings to becoming a respected master reflects not only his artistic dedication but also the socio-cultural currents that swept through Italy during a period of significant transformation. This exploration delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of a painter whose work continues to resonate with its technical brilliance and heartfelt humanism.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Lombardy

Emilio Longoni was born on July 9, 1859, in Barlassina, a small town in Lombardy, then part of the Austrian Empire, which would soon become part of the newly unified Kingdom of Italy. His family background was modest; his father, Matteo Longoni, was a farrier and a Garibaldian volunteer, instilling a sense of patriotic fervor, while his mother, Luigia Meroni, worked as a seamstress. This upbringing in a working-class environment likely sowed the seeds for Longoni's later empathy towards the plight of the common people, a theme that would become central to his artistic expression.

From a young age, Longoni exhibited a natural inclination towards drawing and painting. Recognizing his talent and passion, his family supported his artistic pursuits. After completing his elementary education in Barlassina, the young Emilio made the pivotal move to Milan. This city, a burgeoning industrial and cultural hub, offered far greater opportunities for artistic training and exposure than his provincial hometown. Milan was not just a place of study; it was a crucible of new ideas, artistic movements, and social debates that would profoundly shape Longoni's worldview and artistic trajectory. His early years in Milan were likely marked by the challenges of adapting to a large city and the rigors of beginning a formal artistic education, but his determination was unwavering.

The Brera Academy and the Influence of Scapigliatura

Upon arriving in Milan, Emilio Longoni enrolled at the prestigious Brera Academy of Fine Arts (Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera) in 1877, where he studied painting until 1881. The Brera was a cornerstone of artistic education in Italy, with a rich history and a faculty that included prominent artists. During his time there, Longoni would have received a traditional academic training, focusing on drawing from life, anatomy, perspective, and the study of Old Masters. His professors likely included figures such as Giuseppe Bertini, known for his historical paintings and stained glass.

However, Milan in the late 19th century was also a hotbed for the Scapigliatura movement. The term, translating roughly to "disheveled" or "bohemian," described a group of artists, writers, poets, and musicians who rebelled against bourgeois conventions and academic traditionalism. They sought to blur the lines between art and life, often exploring themes of realism, social critique, and intense emotional states. Key figures of the Scapigliatura in painting included Tranquillo Cremona and Daniele Ranzoni, whose work was characterized by sfumato-like brushwork and a melancholic sensibility.

At Brera, Longoni came into contact with many individuals associated with or influenced by the Scapigliatura. This environment fostered a spirit of intellectual curiosity and artistic experimentation. It was here that he formed crucial friendships and artistic alliances. Among his fellow students and close associates were Giovanni Segantini and Gaetano Previati, both of whom would also become leading figures in Italian Divisionism. The shared experiences and discussions during these formative years at Brera laid the groundwork for their future collaborations and their collective push towards a new, modern Italian art. Carlo Bugatti, the eclectic designer and a lifelong friend, also exerted a significant influence on Longoni's artistic and intellectual development during this period, encouraging his diverse interests.

The Emergence of Italian Divisionism

The late 1880s and 1890s witnessed the rise of Divisionism in Italy, a movement that paralleled French Neo-Impressionism (often called Pointillism, associated with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac) but developed its own distinct characteristics and ideological underpinnings. Divisionism was based on scientific theories of optics, particularly the idea that colors, when applied in small, separate strokes or dots (though Italian Divisionists often used filament-like strokes), would blend in the viewer's eye to create more vibrant and luminous effects than if mixed on the palette.

Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, an art critic, dealer, and painter himself, was instrumental in promoting Divisionism in Italy. He championed artists like Longoni, Segantini, Previati, Angelo Morbelli, and Giovanni Sottocornola, providing them with theoretical grounding and exhibition opportunities. Grubicy's gallery became a focal point for this new avant-garde. Unlike the often more detached scientific approach of some French Neo-Impressionists, Italian Divisionism frequently carried strong symbolic, social, or spiritual connotations. The technique was not merely an end in itself but a means to convey deeper meanings, whether in depicting the radiant light of the Alps or the struggles of the working class.

Emilio Longoni fully embraced the Divisionist technique, finding it an ideal vehicle for his artistic aims. He meticulously applied strokes of pure color, allowing them to interact optically and create an intense vibrancy. His approach was often characterized by elongated, thread-like brushstrokes that followed the forms of his subjects, contributing to both the texture and the luminosity of his canvases. This technique allowed him to capture the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere with remarkable sensitivity, particularly in his landscape paintings.

Themes in Longoni's Art: Social Conscience and Alpine Majesty

Emilio Longoni's artistic output can be broadly categorized into two major thematic concerns: social realism imbued with a critical perspective, and the depiction of nature, especially the sublime landscapes of the Alps. These themes were often intertwined with his Divisionist technique, which enhanced the emotional and visual impact of his subjects.

Social Commentary and Realism

Deeply affected by the social inequalities and labor struggles of his time, Longoni produced a series of powerful works that addressed these issues. Italy was undergoing rapid industrialization, leading to significant social upheaval, urban poverty, and the rise of socialist and anarchist movements. Longoni, with his working-class roots and association with progressive intellectual circles, felt compelled to depict the realities faced by ordinary people.

His most famous work in this vein is undoubtedly L'oratore dello sciopero (The Orator of the Strike), painted in 1890-1891. This painting portrays a charismatic speaker addressing a crowd of striking workers. The composition is dynamic, with the orator positioned centrally, his gestures animated, and the crowd listening intently. Longoni's Divisionist technique, with its fragmented brushstrokes and vibrant color contrasts, heightens the sense of tension and energy. The work was considered politically charged and became an icon of social realist art in Italy. It was even reproduced in socialist publications, underscoring its political resonance.

Another significant work, Riflessioni di un affamato (Reflections of a Hungry Man, 1894), tackles the theme of poverty and social disparity with stark honesty. The painting depicts a destitute man gazing through a restaurant window at a scene of bourgeois opulence. The contrast between the man's gaunt face and the lavish display of food and comfort inside is a powerful indictment of social injustice. Longoni's use of light and color emphasizes the coldness of the street and the warmth of the restaurant, further highlighting the chasm between the two worlds. His work Le bambine chiuse fuori da scuola (Girls Locked Out of School, c. 1890s) also touches upon social themes, possibly alluding to issues of access to education or the vulnerability of children. This painting was notable for being one of his first attempts at a large-scale canvas, showcasing his ambition.

These works placed Longoni firmly within a tradition of socially conscious art, aligning him with other European artists like Jean-François Millet or Honoré Daumier in France, who also depicted the lives of peasants and workers, though Longoni's technique was distinctly modern.

The Majesty of the Alps and Landscape Painting

Parallel to his social concerns, Emilio Longoni developed a profound passion for landscape painting, particularly the majestic scenery of the Alps. He spent considerable time in mountainous regions, such as the Valtellina, drawing inspiration from the dramatic peaks, glaciers, and atmospheric effects. His close friend and fellow Divisionist, Giovanni Segantini, was also renowned for his Alpine landscapes, and the two artists likely shared a mutual influence in their approach to this subject matter.

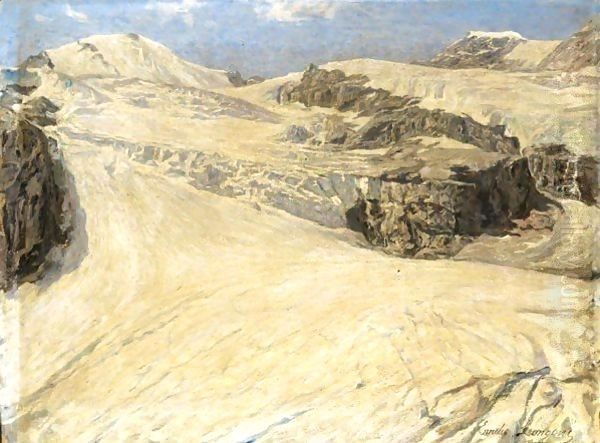

In his landscapes, Longoni's Divisionist technique found its most lyrical expression. He masterfully used fragmented strokes of color – often greens, blues, pinks, and yellows – to capture the shimmering light, the crisp air, and the monumental scale of the mountains. Works like Ghiacciaio (Glacier, c. 1902-1903) and La voce del ruscello (The Sound of the Stream, 1902-1903) exemplify his ability to convey not just the visual appearance of nature but also its sensory and emotional impact. The play of light on snow and ice, the subtle gradations of color in the sky, and the textures of rock and vegetation are rendered with extraordinary sensitivity.

His painting Isola di San Giulio (Island of San Giulio, 1894-1903) demonstrates his skill in capturing the tranquil beauty of lake scenes, with a focus on light and reflection. Another notable landscape, Primavera in alta montagna (Spring in the High Mountains), showcases his ability to infuse these scenes with a sense of renewal and the sublime power of nature. These works often possess a spiritual or pantheistic quality, reflecting a deep connection with the natural world, a sentiment shared by many artists of the Romantic and Symbolist traditions. His landscapes can be compared to those of other European painters who sought the sublime in nature, such as Caspar David Friedrich, though Longoni's approach was filtered through the lens of Divisionist optics.

Key Masterpieces: A Closer Look

Several of Emilio Longoni's paintings stand out as defining achievements of his career, encapsulating his technical mastery and thematic concerns.

L'oratore dello sciopero (The Orator of the Strike, 1890-1891): This iconic work is a cornerstone of Italian social realism and Divisionism. The painting depicts a passionate speaker addressing a crowd of striking workers, likely in an urban setting. Longoni's use of Divisionist technique, with its vibrant, fragmented brushstrokes, creates a dynamic and energetic surface that mirrors the intensity of the moment. The figures are rendered with a sense of immediacy and conviction. The orator, with his raised arm and focused gaze, commands the attention of the crowd, whose faces reflect a mixture of hope, determination, and hardship. The painting's political undertones were clear, aligning with the growing labor movements and socialist ideals of the time. It was a bold statement, demonstrating Longoni's commitment to using art as a tool for social commentary. The work's impact was significant, solidifying Longoni's reputation as a leading voice among socially engaged artists.

Riflessioni di un affamato (Reflections of a Hungry Man, 1894): This painting is a poignant exploration of social inequality. It presents a stark contrast between a destitute, hungry man on the street and the warm, inviting interior of a restaurant filled with well-to-do patrons. The man's face, etched with suffering, is pressed against the cold glass, his gaze fixed on the abundance within. Longoni masterfully uses light and color to emphasize this divide: the exterior is depicted in cool, somber tones, while the restaurant interior glows with warm, inviting light. The Divisionist application of paint adds a shimmering, almost hallucinatory quality to the scene, perhaps reflecting the man's hunger-induced state. This work is a powerful critique of a society that allows such disparities to exist, and it showcases Longoni's deep empathy for the marginalized.

Ghiacciaio (Glacier, c. 1902-1903): Representing his dedication to Alpine landscapes, Ghiacciaio is a testament to Longoni's ability to capture the sublime and ethereal beauty of high mountain scenery. Using his refined Divisionist technique, he renders the immense scale and crystalline structure of the glacier with a dazzling array of blues, whites, and subtle pinks and violets. The light seems to fracture and refract across the icy surfaces, creating an effect of shimmering brilliance. The brushstrokes are often elongated and follow the contours of the ice and rock, enhancing the sense of texture and form. This painting, like many of his Alpine scenes, transcends mere topographical representation; it evokes a sense of awe, solitude, and the timeless power of nature. It reflects a deep, almost spiritual connection to the mountain environment, a theme also explored by his contemporary Giovanni Segantini.

These masterpieces, among others, highlight Longoni's versatility as an artist, capable of tackling both the pressing social issues of his day and the timeless beauty of the natural world with equal skill and passion. His innovative use of Divisionist technique served to amplify the emotional and visual impact of his chosen subjects.

Relationships, Collaborations, and the Divisionist Circle

Emilio Longoni was not an isolated figure; he was an active participant in the vibrant artistic community of Milan and a key member of the Divisionist group. His relationships with fellow artists were crucial for his development and for the advancement of the movement.

His friendship with Giovanni Segantini was particularly significant. They studied together at the Brera Academy and shared a commitment to Divisionism and a love for Alpine landscapes. Their artistic paths often ran parallel, and they undoubtedly influenced each other. Sources suggest that Longoni even provided financial assistance to Segantini during times of hardship, indicating a deep personal bond. Segantini's own international success helped to bring attention to Italian modern art, indirectly benefiting his colleagues.

Gaetano Previati was another close associate from their Brera days. Previati, known for his more Symbolist and often religious or mythological themes, also adopted Divisionist techniques, though his style evolved in a distinct direction. The trio of Longoni, Segantini, and Previati formed a core group that spearheaded the Divisionist movement.

Vittore Grubicy de Dragon played a multifaceted role as a mentor, promoter, and theorist for the Divisionists. His support was vital in providing Longoni and others with exhibition opportunities and in articulating the principles of Divisionism to a wider audience. Grubicy's gallery was a crucial venue, and his writings helped to contextualize their work within the broader European art scene. He encouraged Longoni's development towards naturalism and the depiction of light.

Other important Divisionist painters with whom Longoni would have interacted and exhibited include Angelo Morbelli, known for his poignant depictions of the elderly and his atmospheric landscapes, and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, whose monumental work Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate) became another iconic image of social protest, employing a meticulous Divisionist technique. Plinio Nomellini was another contemporary who explored Divisionist principles, often with a focus on vibrant coastal scenes.

While these artists collaborated and shared common goals, there was also an element of healthy competition and a desire to establish a distinctly Italian modern art. The Divisionists consciously sought to differentiate their work from French Post-Impressionism, emphasizing the scientific rigor and often the social or spiritual content of their art. They participated in major exhibitions, both in Italy (like the Milan Triennales) and internationally, showcasing the vitality of the Italian avant-garde. Longoni's works were frequently exhibited alongside those of his Divisionist peers, contributing to the collective identity of the movement.

Later Years, Legacy, and Market Recognition

Emilio Longoni continued to paint and evolve throughout his career. While his most radical social critiques and pioneering Divisionist works belong to the late 19th and early 20th centuries, he remained a dedicated artist until his death in Milan on November 29, 1932. His later work continued to explore landscape themes, often with a more serene and contemplative mood, though the precision of his Divisionist technique remained a hallmark.

Longoni's legacy is that of a key innovator in Italian art. He successfully synthesized scientific color theory with profound emotional content, creating works that were both visually stunning and intellectually engaging. His contributions to Divisionism helped to place Italian art at the forefront of European modernism at the turn of the century. His socially conscious paintings remain powerful documents of their time, reflecting a deep humanism and a commitment to social justice. His Alpine landscapes are celebrated for their technical brilliance and their ability to evoke the sublime beauty of nature.

Today, Emilio Longoni's works are held in important public and private collections. Museums such as the Galleria d'Arte Moderna in Milan, the Pinacoteca di Brera, and other regional Italian museums feature his paintings. The Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Tortona, for instance, holds his work Melanconia invernale. Many significant pieces, including L'oratore dello sciopero and Natura morta con frutta candita e caramelle, are in private hands, occasionally appearing in major exhibitions.

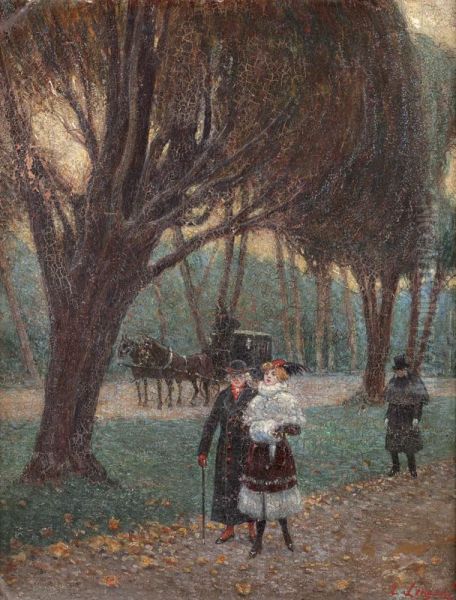

In the art market, Longoni's works command significant respect. While perhaps not achieving the stratospheric prices of some of his French contemporaries like Claude Monet or Vincent van Gogh, his paintings are highly valued, particularly his prime Divisionist pieces. For example, Primavera in alta montagna reportedly fetched a price around €154,450 at auction, indicating a strong market for his major landscapes. Smaller works or studies, such as Promenade au bois de Boulogne (Boulogne Woods), have been estimated in the range of €5,000 to €8,000. The market value of his work, like that of many artists, has fluctuated over time, influenced by art market trends, curatorial attention, and scholarly research that continues to affirm his importance. Exhibitions dedicated to Divisionism or late 19th-century Italian art regularly feature Longoni, further cementing his place in art history.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Emilio Longoni was more than just a skilled technician of the Divisionist method; he was an artist of profound sensitivity and social conscience. His ability to capture the dazzling light of the Alps with the same fervor he depicted the struggles of the urban working class speaks to the breadth of his vision. He navigated the complex artistic and social currents of his time, from the lingering influences of Romanticism and the rebellious spirit of Scapigliatura to the scientific optimism of Divisionism and the rising tide of social awareness.

Alongside contemporaries like Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, Angelo Morbelli, and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, Longoni forged a uniquely Italian path within modern European art. His legacy endures in his luminous canvases, which continue to inspire admiration for their technical mastery and to provoke reflection on the enduring themes of social justice and humanity's relationship with the natural world. As an art historian, one recognizes Emilio Longoni not just as a representative of a movement, but as an individual artist whose unique voice contributed significantly to the rich tapestry of Italian and international art.