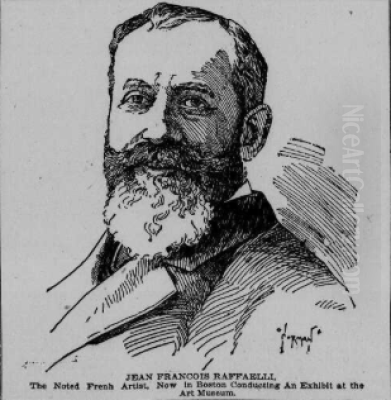

Jean-François Raffaëlli stands as a distinctive figure in the landscape of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century French art. Born in Paris on April 20, 1850, and passing away in the same city on February 11, 1924, Raffaëlli navigated the complex artistic currents of his time, leaving behind a rich legacy as a painter, printmaker, sculptor, and writer. His work is particularly noted for its sensitive and insightful portrayal of Parisian life, especially the often-overlooked realities of its suburbs and the lives of its working-class inhabitants. While associated with Impressionism, he carved a unique path, blending realist concerns with modern techniques.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Raffaëlli's origins were rooted in the Parisian bourgeoisie. His family, of Italian descent, initially provided him with a comfortable childhood. However, the trajectory of his early life shifted dramatically when his father's textile business failed. This financial downturn forced the young Raffaëlli into the workforce at the tender age of fourteen. By sixteen, he found himself employed in a commercial firm, likely working as an accountant, a path far removed from his burgeoning artistic inclinations.

Despite these practical obligations, Raffaëlli harbored a deep passion for art. The pull towards creative expression eventually proved stronger than the demands of commerce. He made the decisive choice to abandon his business career and dedicate himself fully to the pursuit of art. This commitment marked the beginning of a long and multifaceted artistic journey, one deeply informed by his early experiences and observations of the social fabric of Paris.

Forging an Artistic Path

Raffaëlli's formal artistic training was relatively brief but significant. He spent a short period studying at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, under the tutelage of Jean-Léon Gérôme. Gérôme, a prominent figure associated with the Academic tradition, known for his historical and Orientalist paintings, represented a more established approach to art. While Raffaëlli absorbed technical skills, his artistic vision soon diverged from the academic mainstream.

His public debut as an artist occurred in 1870 when he exhibited his first landscape painting at the official Paris Salon. This annual exhibition was the primary venue for artists seeking recognition and patronage. Initially, Raffaëlli explored conventional subjects, including historical scenes and costume pieces. However, his focus soon shifted dramatically towards the contemporary world around him, particularly the landscapes and inhabitants of the Parisian periphery.

The Rise of a Social Realist

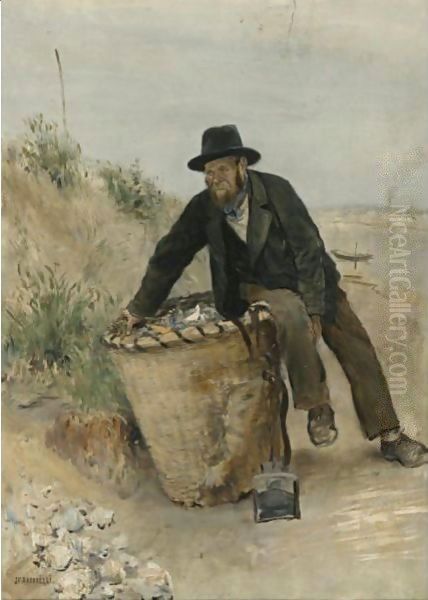

The defining characteristic of Raffaëlli's mature work emerged as he turned his gaze towards the outskirts of Paris – the banlieue. He became fascinated by the lives of those on the margins of the rapidly modernizing city: the factory workers, the peasants clinging to dwindling rural ways, the ragpickers (chiffonniers), and other members of the urban poor. This focus aligned him with the broader Realist movement, which sought to depict contemporary life truthfully, often focusing on the working classes, as seen in the earlier work of Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet.

Raffaëlli approached these subjects with a distinctive blend of objective observation and psychological insight. He sought not just to document their existence but to convey their character, their struggles, and their humanity. His style during this period was often characterized by strong drawing, a somber palette reflecting the gritty reality of his subjects' lives, and an anti-romantic sensibility. He aimed to capture the "character" of the modern individual shaped by their environment. Success came with works like The Family of Jean-le-Boîteux, exhibited at the Salon in 1877, which garnered positive attention after some earlier rejections.

Engagement with Impressionism

Raffaëlli's career intersected significantly with the Impressionist movement, primarily through his complex relationship with Edgar Degas. Degas, known for his own depictions of modern Parisian life, recognized a kindred spirit in Raffaëlli's focus on contemporary subjects, albeit from a different social perspective. Degas championed Raffaëlli and invited him to participate in the Impressionist exhibitions.

Raffaëlli exhibited a substantial number of works – sources mention thirty-five or thirty-seven pieces, including paintings, drawings, and prints – at the Fifth (1880) and Sixth (1881) Impressionist exhibitions. This move, however, proved controversial within the group. Degas hoped to broaden the scope and appeal of the exhibitions by including artists with more explicitly Realist tendencies. However, core Impressionists like Claude Monet and perhaps Gustave Caillebotte (though Raffaëlli was also noted as being part of Caillebotte's circle in the late 1870s) felt that Raffaëlli's style and sheer number of works diluted the group's identity, leading to significant internal friction.

Despite the controversy, Raffaëlli's participation brought his work to wider attention and highlighted the evolving definition of "modern" art. Furthermore, his exposure to Impressionism undoubtedly influenced his own technique. From the mid-1880s onwards, his brushwork often became looser, his palette lightened somewhat, and his interest in capturing the effects of light and atmosphere grew, echoing the concerns of artists like Monet and Alfred Sisley, even as his fundamental focus remained on social observation.

A Unique Stylistic Synthesis: Characterism

While Raffaëlli absorbed elements of Impressionist technique, he never fully identified with the movement's core tenets. He famously referred to himself as a Realist or, more specifically, a "characterist." He believed that art should go beyond capturing fleeting visual sensations – the primary goal of many Impressionists – to delve into the defining character of individuals, social types, and places. He felt some Impressionist works lacked the social weight and psychological depth he sought to convey.

His work, therefore, represents a unique synthesis. He employed modern techniques – broken brushwork, attention to light – learned partly from his Impressionist colleagues, but applied them to subjects rooted in the Realist tradition. He depicted the harsh realities of the banlieue but often with a subtle humanity and sometimes even humor. This blend distinguishes him from both the academic painters and the mainstream Impressionists, placing him closer perhaps to contemporaries like Jean-Louis Forain, who also combined sharp social observation with a modern graphic style.

Master of Multiple Media

Raffaëlli's artistic talents extended well beyond painting. He was a highly accomplished and innovative printmaker, mastering techniques such as etching and drypoint. His prints often revisited the themes found in his paintings – Parisian street scenes, suburban landscapes, and portraits of working-class individuals. Works like Snow Scene and The Blacksmith exemplify his skill in capturing texture, atmosphere, and character through line.

He was a pioneer in the revival of color etching in France. Recognizing the potential of color prints as an original art form, he co-founded the Société de la gravure originale en couleurs (Society of Original Color Printmaking). His collaborators in this venture included prominent artists also exploring color printmaking, such as the American Mary Cassatt and the Impressionist Camille Pissarro. This initiative played a significant role in elevating the status of color prints.

Furthermore, Raffaëlli invented his own artistic medium: solid oil paint sticks known as bâtons Raffaëlli. These sticks offered a unique combination of the richness of oil paint with the directness of drawing tools like pastels or crayons, allowing for vigorous and textured application. He was also a capable sculptor and a prolific writer, authoring numerous articles and books on art theory and social commentary, and even delivering lectures, though some contemporaries reportedly viewed his literary pursuits as a distraction from his visual art.

Chronicler of Paris: From Suburbs to Boulevards

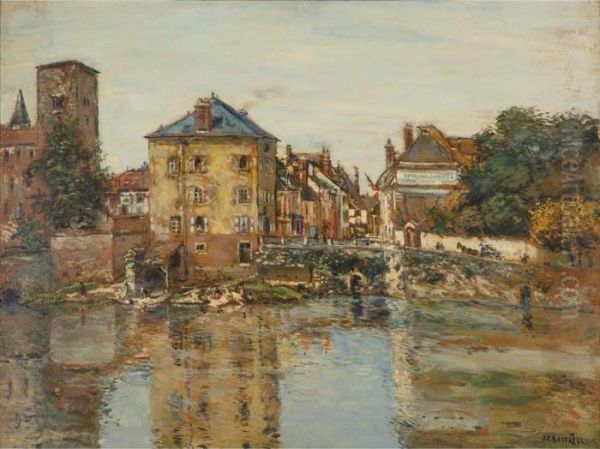

While Raffaëlli initially made his name depicting the often bleak landscapes and marginalized inhabitants of the Parisian suburbs, his focus broadened over time. By the 1890s, he increasingly turned his attention to the heart of Paris itself. He painted the bustling boulevards, the iconic monuments, the cafes, and the vibrant street life of the city center.

His approach, however, retained its characteristic focus on human activity and social nuance. Even when depicting famous landmarks, the emphasis was often on the everyday people interacting with the urban environment. Works like Quai Malakoff capture the atmosphere of the city's embankments, while paintings depicting absinthe drinkers, such as L'Absinthe (a theme also famously tackled by Degas and Édouard Manet), continued his exploration of specific social milieus. His early landscape St. Mark's Basilica, Venice (1870) shows his long-standing interest in place, while works like The Two Old Jews demonstrate his skill in portraiture and character study throughout his career. His Paris is less about the fleeting play of light favored by Monet and more about the social tapestry and lived experience of the modern metropolis.

Recognition, Exhibitions, and Reputation

Throughout his career, Raffaëlli actively sought recognition through various exhibition venues. He remained a consistent participant in the official Paris Salon for decades, from his debut in 1870 until at least 1914. Simultaneously, he frequently showed his work at the more independent Salon des Artistes Indépendants, demonstrating his ability to navigate both established and alternative art worlds. His participation in the Impressionist exhibitions, though brief and contentious, also significantly impacted his visibility.

His work achieved considerable success both in France and internationally, particularly in the United States. He received awards and honors, although specific details are less emphasized than his consistent presence and the growing appreciation for his unique vision. His multifaceted output – paintings, prints, sculptures – ensured a broad reach. He captured a specific aspect of French society during a period of intense transformation, earning him a distinct place in the art historical narrative.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Raffaëlli continued to work, with a particular emphasis on his innovative color printmaking techniques. He remained an active figure in the Parisian art world until his death in 1924. While his reputation may have been somewhat overshadowed during his lifetime by the more radical innovations of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, his critical standing has grown significantly since his passing.

Today, Jean-François Raffaëlli is recognized as a crucial observer and chronicler of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Parisian life. He is valued for his ability to bridge the gap between Realism/Naturalism and Impressionism, creating a style uniquely suited to his subject matter. His focus on the social landscape, particularly the lives of the urban poor and the character of the Parisian suburbs, provides an invaluable visual record of a society undergoing rapid industrialization and modernization. His work resonates with the social concerns explored by earlier artists like Honoré Daumier, but rendered with a distinctly modern sensibility.

His paintings and prints are held in major museum collections around the world, including the Musée d'Orsay and the Louvre in Paris, The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Art Institute of Chicago, among many others. These collections ensure that his sensitive, insightful, and often poignant depictions of Parisian life continue to be studied and appreciated, securing his legacy as a significant artist who captured the complex character of his time.

Conclusion

Jean-François Raffaëlli's career was marked by a steadfast dedication to depicting the world around him with honesty and empathy. As a painter, printmaker, sculptor, and writer, he explored the social fabric of Paris, from its marginalized suburbs to its bustling center. He navigated the currents of Realism and Impressionism, forging a unique "characterist" style that blended modern techniques with profound social observation. His technical innovations, particularly in printmaking and the development of oil sticks, further highlight his creative spirit. More than just an artist associated with a particular movement, Raffaëlli remains an essential visual historian of Parisian modernity, whose work continues to offer compelling insights into the human condition within the evolving urban landscape.