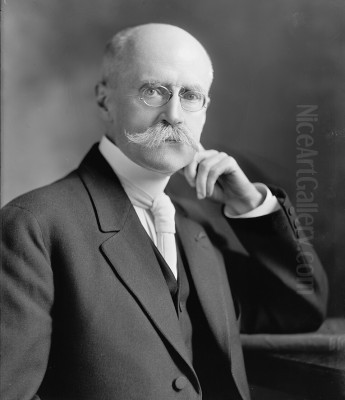

Edwin Howland Blashfield stands as a monumental figure in the history of American art, particularly renowned for his extensive contributions to mural painting during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work, characterized by its classical elegance, allegorical depth, and technical mastery, adorned the walls and domes of some of the nation's most significant public buildings, embodying the aspirations of an era often referred to as the American Renaissance. As an artist, writer, and influential voice in arts organizations, Blashfield left an indelible mark on the cultural landscape of the United States.

Early Life and Artistic Inclinations

Born on December 5, 1848, in Brooklyn, New York, Edwin Howland Blashfield was the son of William Henry Blashfield and Eliza Dodd Blashfield. His early education steered him towards a more practical profession. He attended the prestigious Boston Latin School and subsequently enrolled at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to study engineering. However, the allure of art proved stronger than the rigors of engineering. After two years at MIT, Blashfield made the pivotal decision to dedicate his life to painting.

This decision led him, in 1867, to Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the time. This transatlantic move was a common path for aspiring American artists seeking rigorous academic training and exposure to both historical masterpieces and contemporary artistic currents. Paris offered an environment rich in artistic discourse, competitive salons, and esteemed ateliers that were considered essential for a comprehensive artistic education.

Parisian Training and Formative Influences

In Paris, Blashfield sought out the tutelage of Léon Bonnat, a highly respected academic painter known for his portraiture and historical scenes, and a teacher to many international students, including notable American artists like Thomas Eakins and John Singer Sargent. Under Bonnat, Blashfield would have received a thorough grounding in academic principles: precise draughtsmanship, the study of anatomy, mastery of composition, and the traditional techniques of oil painting. He also reportedly received advice from Jean-Léon Gérôme, another titan of French academic art, known for his meticulously detailed historical and Orientalist paintings.

During his time in Europe, which extended over a decade with intermittent returns to the United States, Blashfield absorbed the prevailing artistic trends. He was undoubtedly influenced by the grand decorative schemes of artists like Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, whose serene, allegorical murals with their simplified forms and muted palettes were highly influential on both sides of the Atlantic. The work of Paul Baudry, particularly his opulent decorations for the Paris Opéra, also provided a model for large-scale allegorical painting. Blashfield diligently honed his skills, and his work began to gain recognition, with exhibitions at the Paris Salon and the Royal Academy in London.

His early easel paintings often depicted historical and mythological subjects, genre scenes, and elegant figures, showcasing a refined technique and a penchant for detailed rendering of costumes and settings. These works laid the foundation for the thematic concerns and compositional strategies that would later define his mural work.

The Shift to Mural Painting and the Chicago World's Fair

While Blashfield initially established himself as an easel painter, his career took a decisive turn towards mural decoration, a field that was experiencing a significant revival in the United States. This shift coincided with the burgeoning "City Beautiful" movement, which advocated for aesthetically pleasing urban environments and the integration of art into public architecture as a means of civic uplift and national expression.

A pivotal moment for Blashfield, and for American mural painting in general, was the World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893. This grand fair, with its "White City" of neoclassical buildings, provided an unprecedented opportunity for American artists to create large-scale decorative works. Blashfield was commissioned to paint murals for the dome of the Manufactures and Liberal Arts Building, one of the largest structures at the exposition. His contribution, notably "The Art of Metal Working," was widely acclaimed.

Working alongside other prominent artists such as Kenyon Cox, Carroll Beckwith, Walter Shirlaw, Stanley Reinhart, J. Alden Weir, and Edward Simmons, under the architectural direction of figures like Daniel Burnham and Charles McKim, Blashfield helped to create a unified artistic vision that captivated the public and demonstrated the potential of mural painting in America. The success of the Chicago Fair significantly boosted the demand for murals in public and private buildings across the country, and Blashfield was perfectly positioned to become a leading figure in this movement.

Masterworks of Mural Decoration: The Library of Congress

Perhaps Blashfield's most celebrated mural commission is "The Evolution of Civilization" (also known as "Human Understanding") located in the dome of the Main Reading Room of the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., completed in 1896. This monumental work, encircling the oculus of the dome, is a complex allegory representing the contributions of twelve historical civilizations or epochs to the development of Western civilization.

The figures, rendered with classical grace and dignity, are arranged in a frieze-like composition. Each nation or epoch—Egypt (Written Records), Judea (Religion), Greece (Philosophy), Rome (Administration), Islam (Physics), The Middle Ages (Modern Languages), Italy (The Fine Arts), Germany (The Art of Printing), Spain (Discovery), England (Literature), France (Emancipation), and America (Science)—is personified by a majestic figure, often accompanied by symbolic attributes. America, for instance, is depicted as an engineer with a dynamo, reflecting the nation's scientific and industrial prowess at the turn of the century.

The Library of Congress project involved a constellation of prominent American artists, including Gari Melchers, Elihu Vedder, John White Alexander, and sculptors like Augustus Saint-Gaudens, all contributing to a cohesive decorative program. Blashfield's dome stands as the crowning achievement of this artistic endeavor, a testament to his ability to synthesize complex allegorical themes into a visually harmonious and intellectually engaging composition.

State Capitols and Other Public Commissions

Following the triumph at the Library of Congress, Blashfield received numerous commissions for murals in state capitols, courthouses, banks, universities, and private residences. His reputation as the "Dean of American Mural Painters" was firmly established.

He created significant works for several state capitols, each tailored to reflect the history, values, and aspirations of the respective state. Notable among these are his murals for the Minnesota State Capitol in St. Paul (designed by architect Cass Gilbert), where he painted "The Discoverers and Civilizers Led to the Source of the Mississippi" and "Minnesota, Granary of the World." For the Iowa State Capitol in Des Moines, he executed the magnificent "Westward," a sprawling mural depicting a pioneer caravan moving towards the setting sun, symbolizing the westward expansion of the nation.

Other important state capitol commissions included works for the Wisconsin State Capitol in Madison, the South Dakota State Capitol in Pierre, and the dome of the Kansas State Capitol in Topeka. He also decorated the Appellate Division Courthouse of New York State, where he contributed to a collaborative project involving ten artists, and the Hudson County Courthouse in Jersey City. His murals often featured allegorical figures representing concepts such as Law, Justice, Power, Wisdom, and Progress, rendered in his signature classical style.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Influences

Blashfield's artistic style was deeply rooted in the academic tradition, emphasizing strong draughtsmanship, balanced compositions, and idealized human forms. His figures are typically statuesque and graceful, often draped in flowing classical robes. His color palettes, while rich, were generally harmonious and controlled, suitable for large-scale architectural decoration. He was a master of foreshortening and perspective, essential skills for painting on curved surfaces like domes and vaults.

His primary influences included the masters of the Italian Renaissance, particularly Raphael and Michelangelo, whose grand compositions and idealized figures provided a timeless model for monumental art. The influence of French academic painters like Bonnat and Gérôme remained evident in his technical precision, while the decorative sensibility of Puvis de Chavannes informed his approach to creating murals that harmonized with their architectural settings.

Thematically, Blashfield's work reflected the prevailing cultural optimism and national pride of the Progressive Era. His murals often celebrated American history, democratic ideals, the rule of law, the pursuit of knowledge, and technological advancement. They were intended to be didactic, to instruct and inspire the public, embodying the belief that art could play a vital role in shaping civic virtue and national identity. Allegory was his primary mode of expression, allowing him to convey abstract concepts through personification and symbolism.

Collaborations and the Artistic Milieu

Blashfield was an active participant in the vibrant artistic community of his time. The American Renaissance saw close collaboration between painters, sculptors, and architects. He worked alongside many of the leading artists of the day. Beyond those already mentioned in connection with the Chicago Fair and the Library of Congress, his contemporaries and sometimes collaborators included the sculptor Daniel Chester French, with whom he often worked on war memorials, and the painter and stained-glass artist John La Farge, another pioneer of American mural painting.

He was also connected with figures like the architect Cass Gilbert, for whom he executed murals in several buildings, and painters such as Abbott Handerson Thayer and Maxfield Parrish, who, though distinct in their styles, were part of the broader movement towards a more decorative and classically inspired American art. Blashfield's ability to work effectively within these collaborative environments was crucial to the success of many large-scale public art projects.

Writings and Advocacy for Mural Painting

Edwin Howland Blashfield was not only a prolific painter but also an articulate writer and advocate for his art form. He authored several influential books and articles, including "Mural Painting in America" (1913) and "Italian Cities" (1900, co-authored with his first wife, Evangeline Wilbour Blashfield). In "Mural Painting in America," he passionately argued for the importance of murals in public life, emphasizing their educational value and their capacity to foster a sense of shared cultural heritage.

He believed that mural painting was the most democratic form of art, accessible to all citizens within public spaces. He championed the idea that art should not be confined to museums and private collections but should be an integral part of the civic environment. His writings provided a theoretical framework for the American mural movement and helped to elevate its status within the art world.

Blashfield was also deeply involved in numerous arts organizations. He served as President of the National Academy of Design from 1920 to 1926, and was also President of the Society of American Artists and the National Society of Mural Painters (which he helped found). Through these roles, he exerted considerable influence on arts policy, education, and the commissioning of public art.

Personal Life and the Influence of Grace Hall

In 1881, Blashfield married Evangeline Wilbour, a writer with whom he collaborated on "Italian Cities." After her death, he married Grace Hall in 1928. Grace Hall Blashfield, who was also an artist, became an important partner in his later life and work. Some accounts suggest that her influence led to a subtle shift in his depiction of female figures, perhaps imbuing them with a greater sense of dynamism or a different kind of strength, moving from purely ethereal allegories to figures with more palpable energy. For instance, his work on "Triumph of the Dance" for Yale University's art department reportedly reflected this evolving sensibility.

An amusing anecdote involves Mark Twain visiting Blashfield's studio while the artist was working on "Triumph of the Dance." Upon seeing the figures, Twain is said to have remarked, "I don’t know who they are, but I wish I could be there with them, and in the same costume." This suggests the vivacity and appeal of Blashfield's figures, even to those outside the immediate art world. There is also a minor connection to the literary figure William Makepeace Thackeray through the creation of bookplates, indicating Blashfield's engagement with a broad cultural sphere.

Later Years and Evolving Tastes

Blashfield remained an active and respected figure in the American art world well into the 20th century. He continued to receive commissions and accolades for his work. However, by the 1920s and 1930s, artistic tastes began to shift. The rise of Modernism, with its emphasis on abstraction, personal expression, and a rejection of academic conventions, led to a decline in the popularity of the classical, allegorical style that Blashfield championed.

While his work never fully fell into obscurity, the grand manner of the American Renaissance was increasingly seen as old-fashioned by a new generation of artists and critics. Despite these changing tides, Blashfield remained committed to his artistic principles and continued to produce work of high quality. He received the Gold Medal of Honor from the National Academy of Design in 1911 and numerous other awards throughout his career.

Death and Legacy

Edwin Howland Blashfield passed away on October 12, 1936, in South Dennis, Massachusetts, at the age of 87. He left behind a vast body of work that continues to adorn public buildings across the United States, serving as a visual record of the nation's aspirations at the turn of the 20th century.

His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he was a master of large-scale composition and allegorical representation, creating some of the most iconic murals of the American Renaissance. His work in the Library of Congress, in particular, remains a landmark achievement in American art. As a writer and advocate, he played a crucial role in promoting mural painting and shaping public understanding of its importance. As an organizational leader, he helped to guide the development of American art institutions.

While the style he championed may have been superseded by later artistic movements, Blashfield's historical significance is undeniable. He was a key figure in a period of immense cultural and artistic energy in the United States, a time when artists sought to create a distinctly American visual language that could express the nation's identity and ideals. His murals remain powerful testaments to this ambition, inviting contemporary viewers to engage with the historical narratives and allegorical meanings embedded within them. His contributions ensured that mural painting became a significant and respected component of America's artistic heritage.