Francisco de Zurbarán stands as one of the towering figures of the Spanish Golden Age, a period of extraordinary artistic and cultural flourishing in the 17th century. A contemporary of giants like Diego Velázquez and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Zurbarán carved a unique niche for himself, becoming renowned primarily as a painter of monks, nuns, and martyrs, rendered with a profound sense of spiritual intensity and stark realism. His masterful use of light and shadow, often earning him the moniker "the Spanish Caravaggio," combined with his meticulous attention to detail and texture, created images of quiet devotion, ascetic piety, and haunting beauty that continue to resonate centuries later.

Born in the small town of Fuente de Cantos in the Extremadura region of Spain, baptized on November 7, 1598, Zurbarán's origins were relatively modest. His father, Luis de Zurbarán, was a haberdasher or possibly a shoemaker, and his mother was Isabel Márquez. While traditional accounts emphasize this humble background, recent research suggests a more complex picture. His paternal grandfather, also Luis de Zurbarán, appears to have been a prosperous merchant in Fuente de Cantos, owning property and even slaves, indicating a family background with more substance than previously assumed. This nuanced understanding adds another layer to the artist's journey from provincial life to artistic prominence.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Zurbarán's artistic inclinations must have been apparent early on. In 1614, his father sent him to Seville, the vibrant artistic and commercial hub of Andalusia, to begin his formal training. He entered the workshop of Pedro Díaz de Villanueva, a painter of religious images whose own work is now largely obscure. The apprenticeship lasted approximately three years, until 1617. While Villanueva provided foundational training, Zurbarán's development seems to have been significantly shaped by his independent study of other artists.

Even in his early years, Zurbarán likely absorbed the prevailing artistic currents in Seville. The influence of early Spanish realism, particularly the stark, almost sculptural still lifes of Juan Sánchez Cotán, can be discerned in Zurbarán's later precision and focus on the tangible reality of objects. More significantly, the dramatic naturalism and powerful chiaroscuro (the use of strong contrasts between light and dark) pioneered by the Italian master Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio were making a profound impact across Europe, and Seville was no exception. Zurbarán embraced this tenebrist style, adapting it to his own temperament and subject matter.

Upon completing his apprenticeship in 1617, Zurbarán did not remain in Seville to seek entry into the painters' guild, perhaps avoiding its strict regulations. Instead, he moved to Llerena, a town back in his native Extremadura, where he married María Páez Jiménez. Here, he began his independent career, establishing a workshop and starting to receive commissions, some originating from Seville itself. During this period in Llerena, which lasted over a decade, he honed his skills and began to build a reputation, collaborating at times with local painters like Manuel Rodríguez and José Manuel. He also likely employed assistants to help manage the workload, a common practice for successful artists.

The Seville Period: Rise to Prominence

The year 1626 marked a significant turning point. Zurbarán received a major commission from the Dominican monastery of San Pablo el Real in Seville to paint a series of 21 works, including scenes from the life of Saint Dominic and portraits of prominent Dominicans. This prestigious project, completed over the following years, firmly established his reputation within Seville's demanding artistic scene. The success of the San Pablo commission led to a cascade of further orders from the city's wealthy and influential religious institutions.

In 1628, he was commissioned by the Mercedarian Order in Seville to produce 22 paintings for their cloister, depicting the life of Saint Peter Nolasco, the order's founder. These works, including the harrowing Saint Serapion (1628), showcase Zurbarán's mature style: powerful compositions, dramatic lighting that isolates figures against dark backgrounds, intense psychological realism, and an almost tactile rendering of textures, particularly the heavy white habits of the monks. The Saint Serapion, depicting the martyred Mercedarian friar hanging limply, is a masterpiece of restrained pathos and stark visual impact.

His success was such that in 1629, the Seville City Council formally invited Zurbarán to relocate permanently to the city, a testament to his growing stature. He settled there, establishing a large and productive workshop. He became the favored painter of numerous monastic orders, including the Franciscans, Dominicans, Carthusians, Jeronymites, and Carmelites. Seville, as the gateway to the Americas, also provided a market for exporting religious art, and Zurbarán's workshop produced numerous works destined for churches and monasteries in the New World, particularly in Lima and Buenos Aires. It's estimated over 200 paintings were shipped across the Atlantic, spreading his influence far beyond Spain.

Master of Monastic Life

Zurbarán's name became almost synonymous with the depiction of monastic life. He possessed an extraordinary ability to convey the silent, contemplative world of the cloister. His portraits of monks and saints are not idealized figures but deeply human individuals engaged in profound spiritual experiences. He captured the gravity, the asceticism, and the intense inner life of his subjects with unparalleled sensitivity.

His rendering of fabrics, especially the white habits worn by orders like the Dominicans, Mercedarians, and Carthusians, is legendary. He treated these simple garments with the same meticulous care as a portraitist would a face, capturing the heavy folds, the subtle play of light across the surfaces, and the different textures of wool or linen. These expanses of white are never flat or monotonous; they possess a sculptural quality and contribute significantly to the painting's overall composition and mood, often symbolizing purity and spiritual dedication.

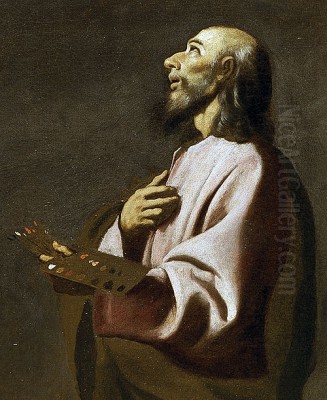

Works like Saint Francis in Meditation (numerous versions exist), The Funeral of Saint Bonaventure, and depictions of Carthusian monks in prayer or ecstasy exemplify this aspect of his art. He often placed solitary figures against dark, undefined backgrounds, using a single, strong light source to illuminate them, enhancing their presence and creating a sense of profound isolation and direct communion with the divine. This focus aligns with the spiritual ideals of the Counter-Reformation, which emphasized personal piety and mystical experience. His patrons among the religious orders clearly found his style perfectly suited to expressing their devotional ideals.

Light and Shadow: The Influence of Caravaggio

The comparison between Zurbarán and Caravaggio is apt, though Zurbarán developed his own distinct interpretation of tenebrism. Like Caravaggio, he used dramatic contrasts of light and dark to heighten the emotional impact and focus the viewer's attention. Light in Zurbarán's paintings often seems to have a divine source, illuminating figures and key details while plunging the surroundings into deep shadow. This technique creates a sense of mystery and transcendence, lifting everyday scenes or depictions of saints into a spiritual realm.

However, Zurbarán's tenebrism is generally quieter and less violent than Caravaggio's. While Caravaggio often depicted moments of intense physical action or brutality, Zurbarán's drama is typically more internal and psychological. His figures are often static, caught in moments of prayer, meditation, or quiet suffering. The light serves not just to create drama but also to reveal the textures of materials – the rough wool of a habit, the smooth skin of fruit, the cold gleam of metal – grounding the spiritual subject in a tangible reality. This blend of intense realism and spiritual elevation is a hallmark of his genius. Other Spanish artists, like Jusepe de Ribera (working primarily in Naples but deeply influential in Spain), also explored tenebrism, but Zurbarán's application remained unique in its focus on stillness and contemplation.

A Sojourn in Madrid and Royal Connections

In 1634, Zurbarán traveled to Madrid. The exact reasons and duration are debated (the provided Chinese text mentions 1634-35, suggesting a shorter stay than the "three years" mentioned elsewhere), but it was a significant trip. It brought him into direct contact with the court of Philip IV and its leading painter, Diego Velázquez. Velázquez, also from Seville, reportedly admired Zurbarán's work and may have facilitated his visit or commissions.

While in Madrid, Zurbarán contributed to a major royal project: the decoration of the Hall of Realms (Salón de Reinos) in the newly built Buen Retiro Palace. Alongside Velázquez and other prominent painters like Vicente Carducho and Eugenio Cajés, Zurbarán was commissioned to paint scenes celebrating Spanish military victories. His contribution was The Relief of Cadiz (1634), a large-scale historical painting depicting a recent naval success against the English. He also painted a series of ten works depicting the Labors of Hercules for the same palace complex.

Working on the Buen Retiro project brought Zurbarán into the orbit of royal patronage. Around this time, he was granted the honorary title of "Painter to the King," although he never held an official salaried position at court like Velázquez. Despite this brush with the court, Zurbarán's temperament and artistic focus remained rooted in religious themes and the patronage of the Church. After his Madrid sojourn, he returned to Seville, his primary base of operations.

The Charterhouse of Jerez and Later Commissions

One of Zurbarán's most important late commissions came between 1638 and 1640, for the Carthusian Monastery (Cartuja) of Nuestra Señora de la Defensión in Jerez de la Frontera. This extensive project included several major altarpieces and individual canvases for the church and sacristy. Key works from this commission include the main altarpiece featuring historical scenes related to the founding of the order and the defense of Jerez, depictions of venerable Carthusian monks, and stunning individual paintings like The Annunciation and The Adoration of the Shepherds.

These Jerez paintings demonstrate Zurbarán at the height of his powers, combining monumental scale with his characteristic intensity and realism. The Adoration of the Shepherds, for instance, is a masterful composition filled with realistic details – the textures of the shepherds' simple clothes, the straw on the floor, the gentle rendering of the Christ Child – all bathed in a dramatic, divine light. He also painted portraits of the four Evangelists (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) for the Cartuja, showcasing his ability to imbue traditional subjects with profound character.

Throughout the 1640s, Zurbarán continued to receive significant commissions in Seville and Andalusia, although the city's economic fortunes began to decline following a devastating plague in 1649, which also impacted artistic patronage.

The Art of Still Life

While primarily known for his religious subjects, Francisco de Zurbarán was also a master of the still life genre (bodegón in Spanish). Although only a handful of signed still lifes by him survive, they are considered among the finest examples in Spanish art. His most famous work in this genre is the Still Life with Lemons, Oranges and a Rose (1633). This painting depicts three distinct elements arranged horizontally on a simple wooden ledge against a dark background: a pewter plate with four citrons, a basket of oranges with blossoms, and a pewter plate holding a single rose beside a cup of water.

The composition is deceptively simple yet profoundly resonant. Each object is rendered with extraordinary precision and sensitivity to texture and form. The light models the objects with clarity, giving them an almost hyper-real presence. The arrangement has a meditative, almost spiritual quality, inviting contemplation. Some scholars interpret the objects symbolically (perhaps relating to the Virgin Mary or the Trinity), while others emphasize the work's formal beauty and Zurbarán's sheer skill in capturing the essence of humble objects.

Another notable example is Still Life with Vessels (c. 1650s), depicting a collection of ceramic and metal jugs and cups. Here again, the focus is on the humble beauty of everyday objects, rendered with intense realism and a masterful handling of light on different surfaces. These works connect back to the tradition of Juan Sánchez Cotán and demonstrate Zurbarán's versatility and his ability to find profound meaning even in the inanimate.

Workshop Practice and Export

Like most successful artists of his time, Zurbarán maintained an active workshop with numerous assistants and pupils. This was essential for fulfilling the large number of commissions he received, particularly the series of paintings for monastic cloisters or for export. Assistants would help with preparing canvases, grinding pigments, painting backgrounds or less important areas, and making copies or variations of successful compositions.

Among his known pupils and collaborators were Bernabé de Ayala and the brothers Juan and Miguel Polanco. Their work often reflects Zurbarán's style, sometimes making attribution difficult for unsigned workshop pieces. The workshop's output was crucial for Zurbarán's financial success and the dissemination of his style. The demand for religious imagery in the Spanish colonies in the Americas was immense, and Zurbarán's workshop catered extensively to this market, shipping crates of paintings depicting saints, Virgins, and apostles to destinations across the Atlantic. This commercial aspect was an integral part of his career.

Evolution of Style and Later Years

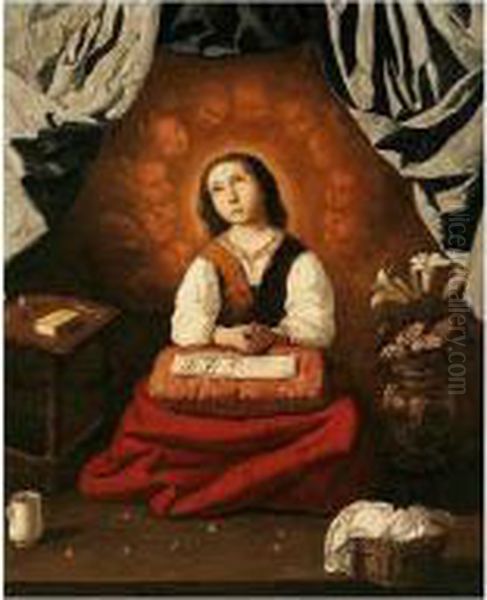

In the later part of his career, particularly from the 1650s onwards, Zurbarán's style underwent a noticeable evolution. While his earlier work was characterized by stark contrasts, sharp outlines, and a somewhat austere realism, his later paintings often feature softer lighting, gentler modeling of forms (sfumato), more delicate color harmonies, and a greater emphasis on tender sentiment.

This shift may have been influenced by several factors. Changing tastes in Seville, partly driven by the rising popularity of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, whose sweeter, more idealized style found great favor, may have encouraged Zurbarán to adapt. Exposure to Italian art, particularly the works of Bolognese painters like Guido Reni and Guercino, known for their softer classicism and emotional warmth, likely also played a role, perhaps through prints or paintings imported into Spain. His own earlier trip to Madrid and contact with the court collection could also have had a delayed impact.

Works from this later period, such as several versions of The Immaculate Conception or Christ Carrying the Cross, often display this gentler, more emotionally accessible approach. While some critics see this later style as less powerful than his starker early work, others appreciate its refined sensibility and delicate beauty.

Facing declining commissions in plague-stricken Seville and perhaps overshadowed by Murillo's immense popularity, Zurbarán moved to Madrid again in 1658, possibly seeking new opportunities or court connections through his friend Velázquez. He spent the last years of his life there, continuing to paint but perhaps in somewhat reduced circumstances compared to his peak years of fame. Francisco de Zurbarán died in Madrid on August 27, 1664.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Zurbarán's career unfolded within the rich artistic landscape of Spain's Siglo de Oro. His interactions, influences, and comparisons with other artists are crucial to understanding his place:

Caravaggio: The foundational influence for Zurbarán's tenebrism, though Zurbarán adapted it to a more Spanish sensibility focused on quiet piety.

Juan Sánchez Cotán: An earlier master whose starkly realistic still lifes likely influenced Zurbarán's approach to objects and texture.

Pedro Díaz de Villanueva: His initial teacher in Seville, providing basic training.

Diego Velázquez: A fellow Sevillian and the dominant figure at the Madrid court. They knew each other, collaborated on the Buen Retiro project, and Velázquez may have aided Zurbarán. Their styles and career paths differed significantly, with Velázquez focused on portraiture and court life, while Zurbarán remained primarily a religious painter.

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo: Another Sevillian contemporary whose softer, sweeter Baroque style eventually eclipsed Zurbarán's popularity in Seville. Murillo's influence may be seen in Zurbarán's later stylistic shift.

Alonso Cano: A versatile artist from Granada, active as a painter, sculptor, and architect, who also worked in Seville and Madrid. His style blended classical ideals with Baroque dynamism.

Jusepe de Ribera: A Spanish painter who spent most of his career in Naples. Like Zurbarán, he was a master of tenebrism and intense realism, often depicting martyrs and aged saints with unflinching detail.

Francisco Pacheco: Velázquez's father-in-law and teacher, a prominent painter and theorist in Seville. Pacheco's circle represented the intellectual hub of Sevillian art life during Zurbarán's early career.

Juan de Valdés Leal: A later Seville Baroque painter known for his dramatic and often macabre vanitas paintings, representing a different, more overtly theatrical strand of the Baroque compared to Zurbarán's restraint.

Workshop Collaborators: Bernabé de Ayala, Juan and Miguel Polanco, and others who helped produce the large volume of work associated with his name.

Italian Influences (Later): Painters like Guido Reni and Guercino, whose softer style likely impacted Zurbarán's later works.

Understanding Zurbarán requires seeing him within this dynamic network of influence, collaboration, and sometimes rivalry.

Death and Rediscovery

After Zurbarán's death in 1664, his reputation gradually faded during the 18th century as artistic tastes shifted towards the lighter Rococo style and later Neoclassicism. His severe, deeply religious works seemed out of step with the Enlightenment era. Many of his paintings remained hidden away in the monasteries and churches for which they were created, contributing to his relative obscurity.

However, the 19th century brought a renewed appreciation for Zurbarán. The Napoleonic Wars led to the dispersal of many artworks from Spanish religious institutions, bringing his paintings to wider attention, particularly in France. The Romantic movement, with its interest in history, religion, and intense emotion, found resonance in Zurbarán's powerful imagery. Artists and critics began to recognize his unique genius, praising his realism, his psychological depth, and his mastery of light and form. Major exhibitions in the 20th century further solidified his status as one of Spain's greatest masters.

Legacy and Influence

Francisco de Zurbarán's legacy is profound and multifaceted. He remains one of the quintessential painters of the Spanish Golden Age, celebrated for his unique ability to portray the spiritual life with intense realism and quiet dignity. His influence extended geographically to Latin America through the extensive export of his workshop's paintings, shaping religious art in the colonies.

His technical mastery, particularly his handling of light and texture, continues to impress. His depictions of white fabrics are legendary, and his still lifes are considered pinnacles of the genre. While his direct influence on subsequent generations of painters might be less obvious than that of Velázquez or Murillo, his work has inspired artists across different eras.

In the modern era, artists like Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí acknowledged their debt to the Spanish masters, including Zurbarán. His stark compositions, focus on form, and blend of realism and mysticism have resonated with modern sensibilities. Even the world of fashion has drawn inspiration from him; the renowned Spanish couturier Cristóbal Balenciaga admired the sculptural simplicity and dramatic forms in Zurbarán's depictions of monastic robes, echoing them in his own designs.

Today, Francisco de Zurbarán is universally recognized as a master painter. His works are prized possessions of major museums worldwide, including the Prado Museum in Madrid, the Louvre in Paris, the National Gallery in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. He is admired not just for his technical brilliance but for his profound exploration of faith, humanity, and the quiet power of contemplation.

Conclusion

Francisco de Zurbarán navigated the complex world of 17th-century Spain to create an body of work that is both deeply rooted in its time and timeless in its appeal. From his early training in Seville to his major commissions for powerful monastic orders and his brief engagement with the royal court, he forged a distinctive artistic identity. His mastery of chiaroscuro allowed him to infuse scenes of religious devotion and simple still lifes with extraordinary presence and spiritual weight. As the "painter of monks," he captured the austere beauty and intense inner life of the cloister like no other. Though his fame fluctuated after his death, his rediscovery cemented his place as a giant of the Spanish Baroque, an artist whose powerful, contemplative images continue to speak to the enduring human search for meaning and transcendence.