Kenneth Hayes Miller stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century American art. A painter, etcher, and influential teacher, Miller dedicated his career to capturing the essence of modern urban life, particularly in New York City, through a lens that uniquely blended classical techniques with contemporary subject matter. His work, deeply rooted in the traditions of the Old Masters, offered a distinct counterpoint to the rising tide of European modernism, and his decades of teaching at the Art Students League of New York shaped a generation of American artists. This exploration delves into his life, artistic evolution, key works, and the profound impact he had on his students and the broader American art scene.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born on March 11, 1876, in Oneida, New York, Kenneth Hayes Miller's artistic journey began in a community known more for its utopian social experiments than its contributions to the fine arts. His father, George Miller, was a cabinetmaker whose interest in the Oneida Community, a perfectionist religious communal society, led the family there. However, Miller's artistic inclinations soon led him to the bustling metropolis of New York City, the burgeoning center of American art.

He embarked on his formal artistic training at the Art Students League of New York, a pivotal institution that would later become his long-term teaching base. There, he studied under prominent figures such as Henry Siddons Mowbray, known for his mural work and adherence to academic principles, and the influential painter and muralist Kenyon Cox, a staunch advocate for classical traditions. Miller also attended the New York School of Art (formerly the Chase School), where he learned from William Merritt Chase, a leading American Impressionist and an inspiring teacher renowned for his bravura brushwork and emphasis on direct observation.

A formative experience in Miller's early development was a trip to Europe in 1899-1900. This journey exposed him firsthand to the masterpieces of the European tradition, particularly the Italian Renaissance and Baroque painters. He was deeply impressed by the compositional strength, the solidity of form, and the rich, luminous color achieved by artists like Titian and Peter Paul Rubens. This exposure would prove crucial, instilling in him a lifelong respect for traditional craftsmanship and techniques, such as underpainting and glazing, which he would later adapt to his own unique vision.

Upon his return to the United States, Miller began to synthesize these influences. Initially, his work bore the imprint of American Romanticism, particularly the mystical and poetic paintings of Albert Pinkham Ryder. Ryder's deeply personal, often enigmatic, and thickly painted canvases, with their emphasis on mood and inner vision, captivated Miller. Early paintings by Miller from this period often feature dreamlike landscapes and figures imbued with a sense of quiet contemplation, reflecting Ryder's introspective approach. This early phase demonstrated Miller's capacity for poetic expression, a quality that, though transformed, would subtly underpin even his most realistic later works.

The Transition to Urban Realism and Renaissance Techniques

The early decades of the 20th century were a period of immense change in the art world, with movements like Fauvism, Cubism, and Futurism challenging established artistic conventions. While many American artists eagerly embraced these European avant-garde styles, Miller charted a different course. Around the 1920s, a significant shift occurred in his artistic focus and technique. He began to turn his attention away from romantic and allegorical themes towards the tangible reality of contemporary urban life, specifically the burgeoning consumer culture of New York City.

Crucially, Miller did not abandon his reverence for the Old Masters; instead, he sought to apply their enduring principles and meticulous techniques to modern subjects. He became a devoted practitioner of underpainting – creating a monochromatic foundational layer for a painting – followed by the application of multiple thin layers of transparent glazes. This laborious process, favored by Renaissance and Baroque artists, allowed for the creation of deep, resonant colors and a luminous surface quality. Miller believed that these traditional methods could imbue contemporary scenes with a sense of permanence and gravitas.

His subject matter became increasingly focused on the shoppers, store windows, and street life of New York, particularly the area around Union Square and Fourteenth Street. He was fascinated by the "New Woman" of the era – often middle-class women navigating the department stores and public spaces of the city. These figures, typically depicted as robust and somewhat monumental, became a hallmark of his mature style. Miller's approach was observational rather than overtly critical or satirical; he aimed to capture the character and social dynamics of these everyday scenes with a degree of classical detachment. Artists like Honoré Daumier, with his incisive yet empathetic portrayals of Parisian life, might be seen as a spiritual predecessor in this regard.

The Fourteenth Street School and Its Vision

In 1923, Kenneth Hayes Miller moved his studio to 30 East Fourteenth Street, a location that placed him directly in the heart of a bustling commercial district. This area, with its department stores, theaters, and diverse populace, provided him with an endless source of inspiration. It also became the symbolic center of what would later be termed the "Fourteenth Street School," a loose affiliation of artists who shared Miller's interest in depicting the urban scene with a realist sensibility.

Miller was undoubtedly the intellectual and artistic anchor of this group. While not a formal "school" with a manifesto, the artists associated with it, many of whom were his students, shared a commitment to figurative art and the depiction of everyday New York life. They largely eschewed the abstract tendencies of European modernism and the more overtly political or sentimental approaches of some other American Scene painters. Instead, they focused on the human element within the urban environment, often with a focus on working-class or middle-class individuals.

His paintings from this period, such as "Shopper" (1928) and "The Fitting Room" (c. 1931-1940), exemplify his mature style. The figures are often full-bodied, almost sculptural, their forms carefully modeled to convey a sense of weight and volume. Compositions are deliberately structured, often employing a shallow pictorial space reminiscent of classical friezes or Renaissance groupings. There's a certain gravity to these scenes; even in the midst of commercial activity, his figures possess a kind of stoic dignity. Miller was not interested in fleeting impressions but in capturing what he perceived as the enduring, almost timeless, aspects of human interaction within the modern city.

Other prominent artists associated with the Fourteenth Street School include Reginald Marsh, Isabel Bishop, and the Soyer brothers, Raphael and Moses. Marsh, perhaps the most famous of Miller's students, depicted the more boisterous and crowded aspects of city life – burlesque shows, Coney Island, and the Bowery – with a dynamic energy. Isabel Bishop, another devoted student, focused on more intimate portrayals of working women and office girls, often captured in moments of quiet repose or interaction, her style characterized by a delicate, almost ethereal quality. The Soyer brothers also contributed significantly to the depiction of urban life, often with a more pronounced social consciousness. Though their individual styles varied, they all benefited from Miller's emphasis on solid draftsmanship and compositional structure.

An Influential Teacher: Shaping a Generation at the Art Students League

Kenneth Hayes Miller's impact as an artist is inextricably linked to his long and distinguished career as an educator. He began teaching at the New York School of Art in 1900, but it was his tenure at the Art Students League of New York, starting in 1911 and continuing with some interruptions until 1951, that cemented his reputation as one of the most influential art teachers of his generation. For four decades, he guided and mentored countless students, many of whom went on to achieve significant recognition.

His teaching philosophy was grounded in his deep respect for tradition and craftsmanship. He emphasized the importance of rigorous drawing, a thorough understanding of anatomy, and the systematic, layered painting techniques of the Old Masters. Miller encouraged his students to study the great art of the past, not to merely imitate it, but to understand its underlying principles of design, form, and color. He believed that a strong technical foundation was essential for any artist, regardless of their ultimate stylistic direction.

Among his notable students, beyond Marsh and Bishop, were George Bellows, who studied with Miller early in his career before becoming a leading figure associated with the Ashcan School; Edward Laning, known for his murals and urban scenes; Paul Cadmus, whose meticulously rendered and often controversial works explored social themes and human sexuality; Yasuo Kuniyoshi, who developed a distinctive style blending Eastern aesthetics with Western modernism; and Peggy Bacon, a talented printmaker and caricaturist. Even artists who later diverged significantly from Miller's specific aesthetic, like the abstract expressionist Barnett Newman who briefly studied with him, acknowledged the rigor of his instruction.

Miller's classroom was known for its intellectual atmosphere. He was a thoughtful and articulate teacher, capable of dissecting the formal qualities of a painting with great clarity. He encouraged his students to think critically about art and its role in society. While he himself was wary of what he considered the excesses of modernism, he fostered an environment where students could explore their own paths, provided they were grounded in solid artistic principles. His dedication to teaching was profound, and his influence extended far beyond mere technical instruction; he instilled in his students a sense of the seriousness and dignity of the artistic endeavor.

Master of the Etching Needle

Alongside his painting, Kenneth Hayes Miller was a dedicated and accomplished printmaker, particularly in the medium of etching. He began making etchings around 1919 and continued to explore the medium throughout his career, producing a significant body of work that often paralleled the themes and compositions of his paintings. For Miller, printmaking was not a secondary activity but an integral part of his artistic practice, allowing him to explore variations on his favorite subjects and to disseminate his imagery to a wider audience.

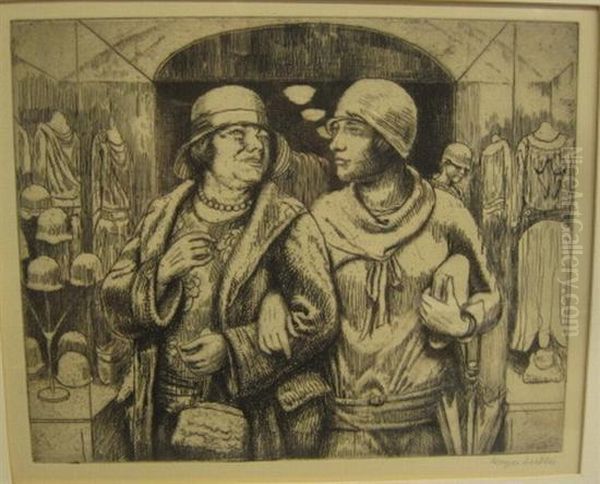

His etchings frequently depict the same scenes of shoppers, women in department stores, and street encounters that characterized his paintings. Works like "Leaving the Shop" (1929) and "Bargain Hunters" (1930) translate the solidity and compositional structure of his painted figures into the linear medium of etching. He demonstrated a fine control of the etching needle, creating rich tonal variations through carefully hatched and cross-hatched lines. There is a palpable sense of volume and plasticity in his etched figures, a testament to his strong draftsmanship.

Miller's approach to etching, like his painting, was rooted in traditional techniques. He admired the work of Old Master printmakers such as Rembrandt, whose mastery of light and shadow and profound humanism clearly resonated with him. Miller's prints often possess a similar sense of gravitas and psychological depth, even when depicting seemingly mundane subjects. He explored the interplay of light and dark to model form and create atmosphere, lending his urban scenes a timeless quality. The accessibility of prints also aligned with his democratic leanings and his interest in art that could engage with a broader public. His etchings were exhibited regularly and collected by museums and private individuals, contributing significantly to his reputation during his lifetime.

Artistic Philosophy, Social Commentary, and Relationship with Modernism

Kenneth Hayes Miller's artistic philosophy was complex and, in some ways, contrarian for his time. He held a deep conviction that art should be rooted in human experience and possess a social dimension. A self-proclaimed socialist, he believed that art had a role to play in reflecting and commenting on contemporary society. However, his approach to social commentary was nuanced. Unlike some of his contemporaries who engaged in more overt political protest or social realism, Miller's observations were generally more subtle, embedded in his depictions of everyday life.

His focus on the "shopper" type, for instance, can be interpreted as an exploration of the burgeoning consumer culture of the early 20th century. The women in his paintings and prints are often portrayed as active participants in this new commercial world, yet there is often an underlying sense of introspection or even melancholy in their expressions. Miller seemed to be observing the rituals of modern urban life with a keen, almost anthropological eye, capturing both its dynamism and its potential for alienation. When a student, possibly Reginald Marsh, remarked that the people Miller painted on Fourteenth Street were "ugly," Miller famously retorted, "They are ugly; they are human." This anecdote encapsulates his commitment to an unvarnished, yet empathetic, portrayal of humanity.

Miller's relationship with modernism was one of critical engagement rather than outright rejection, though he was often perceived as an opponent of its more radical forms. He was certainly wary of what he saw as the superficiality or nihilism of certain avant-garde trends, particularly those that seemed to dispense with skill and tradition. He believed that "good art" was, in its essence, "radical" but that this radicalism should stem from a profound engagement with life and a mastery of craft, rather than a mere desire to shock or overturn conventions. His insistence on classical techniques could be seen as a conservative stance, yet by applying these techniques to thoroughly modern subjects, he was creating a unique synthesis that was, in its own way, a modern statement.

He admired artists like Thomas Eakins and Winslow Homer, American realists of a previous generation who combined keen observation with strong formal construction. He also looked to European masters like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Jacques-Louis David for their clarity of form and compositional rigor. Miller's aim was to create an art that was both contemporary in its subject matter and timeless in its formal qualities, an art that could speak to the enduring aspects of the human condition even as it recorded the specifics of its time.

Contemporaries and the Broader Artistic Milieu

Kenneth Hayes Miller operated within a rich and diverse American art scene. While he was a central figure in the Fourteenth Street School, his work and influence can be understood in relation to other artistic currents of the time. The Ashcan School, with artists like Robert Henri, John Sloan, George Luks, and Everett Shinn, had earlier paved the way for the depiction of urban realism, though their approach was often more painterly and anecdotal than Miller's more classically structured compositions. George Bellows, who briefly studied with Miller, carried some of the Ashcan spirit forward but also absorbed Miller's emphasis on solid form.

Other American realists of the period, such as Edward Hopper, also explored themes of urban life and modern alienation, though Hopper's vision was generally more focused on solitude and the psychological landscape of individuals within the city, often with a starker, more simplified style. Guy Pène du Bois, another contemporary, depicted the urban social scene with a satirical edge and stylized, mannequin-like figures, offering a different perspective on the modern condition.

The rise of American Regionalism, championed by artists like Thomas Hart Benton, Grant Wood, and John Steuart Curry, represented another facet of the reaction against European modernism, focusing on rural American life and values. While Miller's focus was resolutely urban, he shared with the Regionalists a commitment to representational art and American subjects.

Miller's dedication to traditional techniques also set him apart from artists who were more directly influenced by European modernism, such as those in the circle of Alfred Stieglitz, including Georgia O'Keeffe, Marsden Hartley, and John Marin. While O'Keeffe, for example, had also studied at the Art Students League (though not with Miller, primarily with William Merritt Chase), her artistic path led her towards a more abstract and personally symbolic form of modernism. Miller's insistence on the figure and on Renaissance-inspired methods provided a distinct alternative to these more avant-garde approaches.

Later Years, Death, and Enduring Legacy

Kenneth Hayes Miller continued to paint and teach into his later years, remaining a respected, if somewhat conservative, figure in the American art world. He exhibited regularly, and his works were acquired by major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, and the Phillips Collection. However, as the 20th century progressed, Abstract Expressionism emerged as the dominant force in American art, and representational painting, particularly of Miller's traditionalist bent, fell somewhat out of critical favor.

He passed away on January 1, 1952, in New York City. In the years immediately following his death, his reputation, like that of many realists of his generation, experienced a period of relative neglect as the art world's attention shifted decisively towards abstraction. However, the 1970s and 1980s saw a renewed interest in American realism and figurative art, leading to a re-evaluation of Miller's contributions. Scholars and curators began to look again at his work, recognizing its technical skill, its insightful portrayal of urban life, and its importance within the context of early 20th-century American art.

His legacy is twofold. Firstly, there is his own body of work – paintings and etchings that offer a unique window into the social and cultural landscape of New York City during a period of significant transformation. His depictions of shoppers and street scenes, rendered with a classical solidity, remain compelling documents of their time. Works like "The Hat Window" (1930), "By the Window" (1928), and the etching "Leaving the Bank" (c. 1929) are considered representative of his mature vision, capturing the everyday dramas and typologies of urban existence.

Secondly, and perhaps equally importantly, is his profound influence as a teacher. Through his decades at the Art Students League, he shaped the artistic development of a significant cohort of American artists. His emphasis on craftsmanship, his deep knowledge of art history, and his ability to inspire critical thinking left an indelible mark on his students, even those who ultimately pursued very different artistic paths. He helped to sustain a tradition of figurative painting in America during a period when it was increasingly challenged by abstraction.

Conclusion: A Reassessment of Miller's Place

Kenneth Hayes Miller was an artist of conviction and consistency. In an era of rapid artistic change and experimentation, he remained steadfast in his belief in the enduring power of traditional techniques and the importance of depicting the human experience. His unique fusion of Renaissance methods with contemporary urban subject matter created a body of work that is both a product of its time and possessed of a timeless quality.

While he may not have achieved the same level of widespread fame as some of his more avant-garde contemporaries or even some of his own students like Reginald Marsh or George Bellows, Miller's contribution to American art is undeniable. As a painter, he captured the character of New York City and its inhabitants with insight and empathy. As a printmaker, he extended his vision to a wider audience. And as a teacher, he nurtured the talents of a generation, instilling in them a respect for craft and a serious approach to art-making. His role as a central figure of the Fourteenth Street School and his broader impact on American realism secure his place as an important and fascinating artist in the story of American art. The ongoing appreciation for his work affirms his belief in an art that is deeply connected to both the past and the present, an art that finds the universal in the particularities of everyday life.