George de Forest Brush (1855–1941) stands as a significant, if sometimes enigmatic, figure in the landscape of American art. His career traversed the meticulous academicism learned in Paris, the romanticized depictions of Native American life, and the tender, Renaissance-inspired portrayals of motherhood and family. Brush was an artist who sought to reconcile the classical traditions of European art with distinctly American subjects and sensibilities, creating a body of work that reflects both the aspirations and anxieties of his era. His journey from the studios of Paris to the plains of the American West, and finally to the quietude of his New England home, mirrors a broader American search for cultural identity at the turn of the 20th century.

Early Life and Formative Artistic Education

Born on September 28, 1855, in Shelbyville, Tennessee, to Alfred Clark Brush and Nancy Douglas (or Whelpley) Brush, George de Forest Brush's artistic inclinations emerged early. His family, which had New England roots, moved to Danbury, Connecticut, during his childhood. This upbringing in a more established part of the country likely provided a contrast to the frontier themes he would later explore. His formal artistic training commenced in New York City at the prestigious National Academy of Design. Founded in 1825 by artists like Samuel F.B. Morse, Asher B. Durand, and Thomas Cole, the Academy was a cornerstone of American art education, emphasizing drawing from casts and life models, a traditional approach that laid a strong foundation for aspiring painters.

During his time at the National Academy, Brush would have been exposed to the prevailing artistic currents in America. The Hudson River School, with its majestic landscapes by artists like Frederic Edwin Church and Albert Bierstadt, was still influential, though its dominance was waning. A newer generation, many of whom, like Brush, would seek training abroad, was beginning to look towards European academicism and the burgeoning Impressionist movement for inspiration.

The Parisian Crucible: Jean-Léon Gérôme and the École des Beaux-Arts

Recognizing the limitations of American art instruction at the time, Brush, like many ambitious young American artists of his generation, set his sights on Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world. Around 1874, he enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts, the premier art institution in France. There, he entered the atelier of Jean-Léon Gérôme, one of the most renowned academic painters of the 19th century. Gérôme, a master of historical, mythological, and Orientalist scenes, was known for his meticulous draftsmanship, polished finish, and emphasis on anatomical accuracy. His studio attracted a host of international students, including other Americans such as Thomas Eakins, Frederick Arthur Bridgman, and Abbott Handerson Thayer, the last of whom would become a lifelong friend and artistic compatriot of Brush.

Under Gérôme's tutelage, which lasted for approximately six years, Brush absorbed the rigorous discipline of French academic training. This involved countless hours spent drawing from plaster casts of classical sculptures and from live models, mastering anatomy, perspective, and composition. Gérôme's influence is evident in Brush's early work, particularly in its precise rendering of form and its often historical or exotic subject matter. The emphasis on strong narrative and carefully constructed compositions, hallmarks of Gérôme's style, would also inform Brush's approach throughout his career, even as his subjects evolved. The competitive environment of the École and the broader Parisian art scene, with its Salons and lively debates, undoubtedly sharpened Brush's skills and broadened his artistic horizons.

Encounters with the American West: Depicting Native American Life

Upon his return to the United States around 1880, Brush embarked on a series of journeys to the American West, a decision that would profoundly shape the first major phase of his career. He traveled to territories including Wyoming and Montana, living among various Native American tribes, notably the Arapaho, Shoshone, and Crow (referred to in some older sources, possibly with phonetic variations or misinterpretations, as "Shamino" or "Krenken," though Arapaho, Shoshone, and Crow are the more commonly cited groups he interacted with). This period, from the early 1880s, saw him produce a series of paintings depicting Native American life with a sensitivity and dignity that, while still filtered through a 19th-century European-American lens, often sought to move beyond mere exoticism.

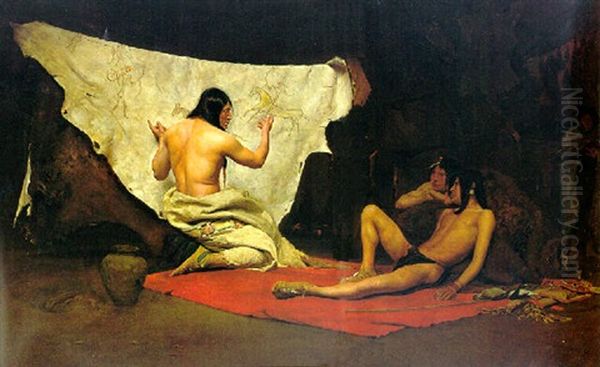

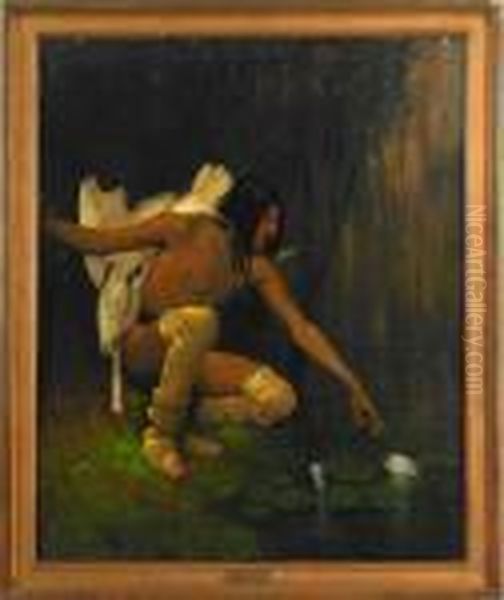

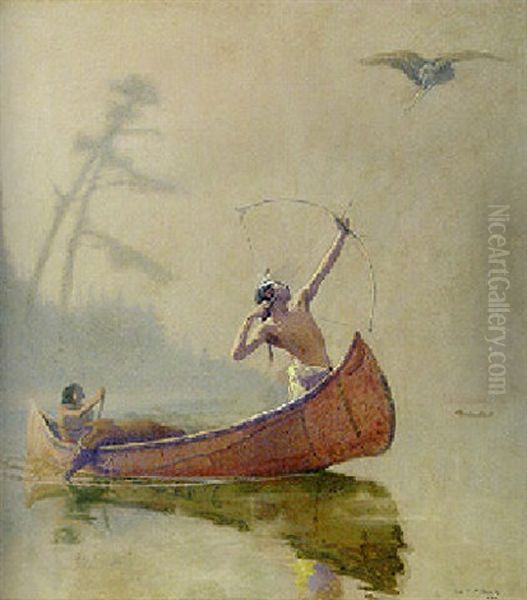

His works from this period, such as The Sculptor and the King (1888, Portland Art Museum), The Picture-Writer's Story (1884), and The Sioux Warrior (also known as The Scalp Hunter in some contexts, though titles can vary or refer to different works), are characterized by their careful observation and technical skill. The Indian and the Lily (1887, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art) is a particularly notable example, portraying a solitary figure in a canoe, embodying a sense of harmony with nature. These paintings were not typically scenes of violent conflict, a common trope in Western art of the time as seen in some works by Frederic Remington or Charles Schreyvogel. Instead, Brush often focused on moments of quiet contemplation, domesticity, or spiritual connection, reflecting his admiration for what he perceived as the noble and stoic character of Native American cultures.

However, it's important to contextualize these depictions. Brush was painting during an era of intense westward expansion, forced assimilation, and the tragic decline of independent Native American nations. His portrayals, while often sympathetic, can also be seen as part of the "vanishing race" narrative, a romanticized view of Native Americans as a people inevitably fading away in the face of modernity. His approach differed from the more ethnographic documentation of artists like George Catlin or Karl Bodmer from earlier in the century, or the action-packed scenes of his contemporary Frederic Remington. Brush's Native Americans were often idealized figures, imbued with a classical grace that reflected his academic training.

A Shift in Focus: The Renaissance Ideal and Familial Themes

By the late 1880s and early 1890s, a noticeable shift occurred in Brush's subject matter. While he never entirely abandoned Native American themes, he increasingly turned his attention to portraits, particularly of his own wife, Mary "Mittie" Taylor Whelpley (who was also his cousin), and their growing family. This transition was partly driven by practical considerations; paintings of Native Americans, while critically noted, did not always find a ready market. Portraits, especially those that resonated with prevailing aesthetic ideals, were more commercially viable.

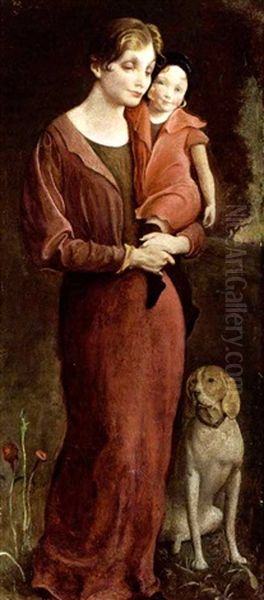

More significantly, this shift reflected a deeper artistic evolution. Brush became increasingly fascinated with the art of the Italian Renaissance, particularly the works of masters like Andrea del Sarto, Raphael, and Donatello. He sought to emulate their harmonious compositions, serene expressions, and the timeless, universal quality of their figures. His "Mother and Child" compositions, which became a signature theme, are direct homages to Renaissance Madonna and Child paintings. Works such as Mother and Child (c. 1892, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) or Mother Reading to Children (1905, Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts) showcase his wife and children in poses and settings that evoke a sense of classical dignity and tender domesticity.

These paintings were not merely sentimental family portraits. Brush imbued them with a sense of idealism and a quasi-religious aura, elevating the theme of motherhood to a universal symbol of love, protection, and cultural continuity. This resonated with the cultural climate of the "American Renaissance," a period when American artists and architects looked to classical and Renaissance models to create a sophisticated national art form. Artists like Abbott Handerson Thayer, with his idealized winged figures, and Augustus Saint-Gaudens, with his classically inspired sculptures, shared this pursuit of beauty and timelessness. Brush's figures, often depicted in circular or tondo formats reminiscent of Renaissance masters, possess a sculptural quality and a quiet emotional depth.

Artistic Style and Technique

George de Forest Brush's artistic style was rooted in the academic tradition, emphasizing strong draftsmanship and a thorough understanding of human anatomy. His training under Gérôme instilled in him a respect for meticulous detail and a polished finish, which is evident in his early Native American paintings. He worked primarily in oils, often on canvas, but also experimented with different supports and formats, including the tondo.

As his style evolved under the influence of the Italian Renaissance, his palette often became richer, and his handling of paint, while still controlled, could exhibit a greater softness and luminosity, particularly in the rendering of flesh tones and drapery. He paid careful attention to composition, often employing pyramidal structures or balanced arrangements that contributed to the sense of harmony and stability in his mother and child groups. His figures possess a tangible presence, a result of his skillful modeling of form through light and shadow. While not an Impressionist in the vein of Mary Cassatt or Childe Hassam, who explored the fleeting effects of light and color, Brush's work demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of light's ability to define form and create mood.

The Dublin Art Colony and Later Life

In the late 1890s, Brush and his family began spending summers in Dublin, New Hampshire, eventually establishing a permanent home there in 1901. Dublin had become a thriving art colony, attracting a community of artists, writers, and intellectuals. Among them was Abbott Handerson Thayer, Brush's old friend from Paris. Thayer was a prominent figure in the colony and a passionate naturalist, known for his theories on protective coloration in animals (camouflage), which he later applied to military contexts during World War I. Brush, too, became involved in camouflage research during the war, developing designs for ships and aircraft. This practical application of artistic principles to a pressing national need was a fascinating, if less known, aspect of his career.

The New Hampshire landscape and the intellectual atmosphere of the Dublin colony provided a supportive environment for Brush's work. He continued to paint his family, and his children often served as models, growing up within an environment steeped in art and creativity. His daughter, Nancy Douglas Bowditch, later wrote a biography of her father, providing valuable insights into his life and work.

Brush was known to be a somewhat reclusive and intensely focused individual. He was deeply committed to his artistic vision and less concerned with the shifting trends of the art world. His dedication to his craft and his chosen themes remained consistent throughout his later years.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Personal Insights

Brush's career was not without its complexities and critiques. The shift from Native American subjects to mother and child portraits prompted some discussion. While financial necessity and market demand likely played a role, as acknowledged by his family, some critics and even his daughter Thea felt he might have done more to advocate for or depict the harsher realities faced by Native Americans. Thea reportedly felt he portrayed them as "deceived friends" rather than fully exploring their plight. This highlights the inherent tension in an artist from a dominant culture depicting a marginalized one, especially during a period of profound injustice.

His depictions of Native Americans, while often admired for their technical skill and romantic appeal, were also seen by some as overly idealized, not fully capturing the raw, often difficult, realities of their lives. This romanticization, however, was common among many artists of the era, including painters like Joseph Henry Sharp or E. Irving Couse of the Taos Society of Artists, who also sought to preserve a vision of Native American culture they saw as disappearing.

Brush's personal life was deeply intertwined with his art. His wife and children were his constant muses. The family's life, particularly their time in Dublin and their travels, which included periods in Florence, Italy, further immersing him in Renaissance art, was central to his artistic output. He was described as a devoted family man, though his intense focus on his work could also make him seem aloof.

Awards, Recognition, and Legacy

George de Forest Brush received significant recognition during his lifetime. He was elected an Associate of the National Academy of Design in 1888 and a full Academician in 1908 (some sources state 1901 for full membership, dates can vary slightly in historical records). He won numerous awards, including a gold medal at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in 1897 and a gold medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900, a testament to his international standing. His work was also exhibited at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

His paintings were acquired by major museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Corcoran Gallery of Art (whose collection is now largely at the National Gallery), and the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. This institutional recognition solidified his place among the leading American painters of his generation.

In art historical terms, Brush is often seen as a key figure in the American academic tradition who successfully integrated classical ideals with American subjects. He is sometimes grouped with the "Boston School" painters, like Edmund C. Tarbell and Frank Weston Benson, for his refined technique and focus on figurative work, though his thematic concerns were distinct. His legacy is twofold: his early Native American paintings remain important documents, however idealized, of a specific moment in American history and art, while his later mother and child compositions are celebrated for their tender beauty and their connection to the enduring traditions of Western art.

Influence and Place in Art History

Brush's influence extended to his students and the broader artistic community. He taught at the Art Students League of New York for a period, sharing his knowledge and rigorous approach. His commitment to craftsmanship and his exploration of universal themes resonated with a desire for an art that was both technically accomplished and spiritually uplifting.

While the rise of modernism in the early 20th century, with movements like Cubism and Fauvism championed by artists such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, would eventually overshadow academic and idealizing traditions, Brush's work has retained its appeal. His paintings offer a window into the cultural aspirations of late 19th and early 20th-century America, a period that sought to establish a distinct national identity while also claiming its place within the broader sweep of Western civilization.

Compared to the stark realism of Thomas Eakins or the Gilded Age bravura of John Singer Sargent, Brush carved out a more introspective and idealized niche. His work stands apart from the burgeoning Ashcan School, led by artists like Robert Henri and John Sloan, who focused on the gritty realities of urban life. Brush, instead, sought refuge and inspiration in the perceived purity of Native American culture and the timeless sanctity of the family.

George de Forest Brush passed away on April 24, 1941, in Hanover, New Hampshire, though he was primarily associated with Dublin. He left behind a body of work that continues to be studied and admired for its technical mastery, its emotional resonance, and its unique blend of American subject matter and classical aesthetics. His art serves as a poignant reminder of a period when American artists grappled with tradition and modernity, seeking to create works of enduring beauty and meaning. His journey reflects a deep engagement with the artistic and cultural currents of his time, making him a vital figure for understanding the complexities of American art at the turn of the century.