Giotto di Bondone stands as a colossus in the history of Western art. Often hailed as the "Father of European Painting," he emerged from the late medieval world to forge a new artistic language, one grounded in observation, human emotion, and a revolutionary sense of realism. Active primarily in Florence, Assisi, Padua, and Rome during the late 13th and early 14th centuries, Giotto broke decisively with the prevailing Byzantine artistic traditions, paving the way for the explosion of creativity that characterized the Italian Renaissance. His life, his works, and his enduring influence mark a pivotal turning point in art history, shifting the focus from stylized representation to the depiction of tangible human experience.

A Life Bridging Eras: From Vespignano to Florence

Pinpointing the exact birth year of Giotto di Bondone remains a subject of scholarly discussion, but it is generally accepted to be around 1267. He was born in Vespignano, a village near Florence, into what appears to have been a family of modest means, likely farmers. His full name, Giotto di Bondone, signifies "Giotto, son of Bondone." The lack of extensive documentation about his earliest years has allowed legends to flourish, the most famous being recounted by the 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari.

According to Vasari, the preeminent Florentine painter Cimabue discovered the young Giotto tending his father's sheep. The boy, using a sharp stone, was sketching one of the sheep onto a flat rock with such remarkable naturalism and life that Cimabue was immediately struck by his innate talent. Recognizing this raw potential, Cimabue supposedly persuaded Bondone to allow Giotto to become his apprentice. While the literal truth of this charming anecdote is uncertain, it serves as a powerful metaphor for Giotto's inherent genius and his deep connection to the observation of the natural world, a hallmark that would define his artistic revolution.

Whether discovered amongst sheep or through more conventional means, it is widely accepted that Giotto received his initial training in the workshop of Cimabue in Florence. Cimabue himself was a leading figure, already pushing the boundaries of the dominant Italo-Byzantine style, seeking greater naturalism and emotional expression than his predecessors. However, Giotto would soon eclipse his master, embarking on a path that fundamentally altered the course of painting. He absorbed the technical skills of fresco and panel painting but infused them with an unprecedented vision.

Breaking the Byzantine Mold

To understand the magnitude of Giotto's achievement, one must consider the artistic landscape he inherited. The prevailing style in Italy during the 13th century was the Italo-Byzantine tradition. This style, derived from the art of the Eastern Roman Empire, emphasized spiritual representation over physical reality. Figures were often elongated, ethereal, and depicted against flat, gold backgrounds symbolizing the divine realm. Compositions were hieratic and symmetrical, emotions were conveyed through stylized gestures, and there was little sense of three-dimensional space or bodily weight. Artists like Coppo di Marcovaldo and Guido da Siena exemplify this earlier tradition.

Cimabue, Giotto's reputed master, had already begun to move away from this rigid formalism. His works, such as the large Crucifix for Santa Croce or the Maestà (Madonna Enthroned) now in the Uffizi, show a greater interest in human pathos and physical presence than earlier Byzantine works. Yet, they still retain many Byzantine conventions. It was Giotto who made the decisive break.

Giotto rejected the flat, symbolic space of Byzantine art. He sought to create a believable, three-dimensional world on a two-dimensional surface. His figures possess a tangible weight and volume, grounded firmly on the earth. He achieved this through careful modeling of form using light and shadow (chiaroscuro), creating a sense of roundness and physical presence that was revolutionary for its time. His figures are not ethereal symbols but appear as solid, flesh-and-blood individuals occupying a real space.

Furthermore, Giotto infused his figures with a profound range of human emotions. While Byzantine art often relied on conventional expressions of sorrow or piety, Giotto depicted joy, grief, tenderness, anger, and contemplation with unprecedented psychological depth. He observed human interaction and translated it into his paintings, making sacred stories accessible and emotionally resonant for the viewer. His narratives unfold with clarity and dramatic power, focusing on the human core of the depicted events.

The Assisi Question: Early Steps Towards Mastery

One of the most significant, yet debated, bodies of work associated with Giotto's early career is the fresco cycle depicting the Legend of Saint Francis in the Upper Church of San Francesco in Assisi. This cycle, comprising twenty-eight scenes, narrates the life of the popular saint with remarkable clarity and humanism. The frescoes depart significantly from Byzantine norms, showcasing figures with volume, expressive gestures, and settings that attempt to create spatial depth.

The attribution of the entire St. Francis cycle solely to Giotto has been a long-standing subject of scholarly debate. Some historians argue that the style is consistent with Giotto's known later works and represents his formative genius. Others suggest the involvement of multiple artists, perhaps including Roman masters like Pietro Cavallini, or that Giotto supervised a workshop executing the designs. Regardless of the precise extent of Giotto's direct hand, the Assisi frescoes are undeniably "Giottesque" in spirit and represent a crucial step towards the naturalism and narrative power that would fully blossom in his later work. They demonstrate a new way of telling stories visually, emphasizing the humanity of the saint and the reality of his experiences.

Padua's Arena Chapel: A Monument of Human Drama

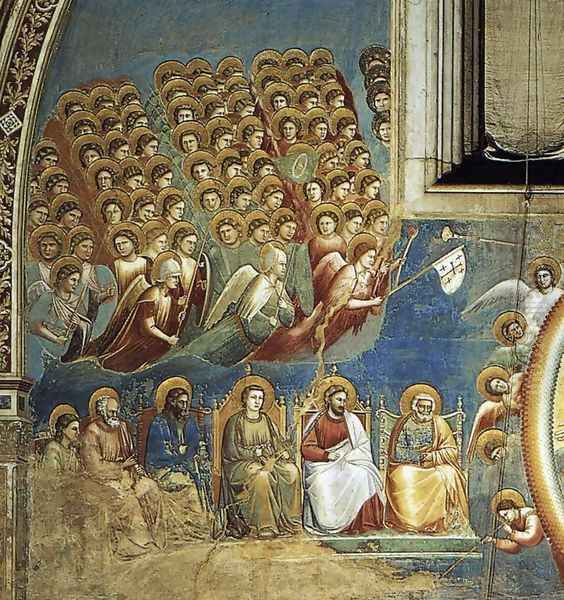

If Assisi represents Giotto's early promise, the Scrovegni Chapel (also known as the Arena Chapel) in Padua is the undisputed testament to his mature genius. Commissioned around 1303-1305 by the wealthy banker Enrico Scrovegni, perhaps partly in atonement for his father's sin of usury (mentioned by Dante in his Inferno), the chapel's interior is entirely covered in frescoes by Giotto and his workshop. This cycle is one of the supreme masterpieces of Western art and Giotto's best-preserved large-scale work.

The narrative program unfolds in three registers, depicting scenes from the lives of the Virgin Mary and her parents, Joachim and Anne, followed by the life and Passion of Christ. Below these narrative scenes, Giotto painted personifications of the Virtues and Vices in grisaille (monochrome), appearing like sculptural reliefs. The barrel-vaulted ceiling is painted a brilliant blue, studded with golden stars and medallions featuring Christ, Mary, and prophets, evoking the heavens.

Within this comprehensive scheme, Giotto's revolutionary style reaches its zenith. Each scene is composed with remarkable clarity and dramatic focus. The figures are monumental, possessing sculptural weight and occupying a convincingly rendered space, often defined by simple but effective architectural or landscape elements. The use of color is both rich and purposeful, contributing to the mood and structure of the compositions.

Scenes like the Lamentation over the Dead Christ are devastating in their emotional impact. The raw grief of the Virgin Mary cradling her son, the despairing gestures of the surrounding figures, and even the anguished angels flailing in the sky convey a depth of human sorrow previously unseen in art. The composition directs the viewer's eye inexorably to the central figures, heightening the drama.

In the Kiss of Judas, the dramatic tension is palpable. The swirling chaos of soldiers and disciples surrounds the central, still moment of betrayal, where the profiles of Christ and Judas meet. Giotto masterfully contrasts Christ's calm resignation with Judas's malevolent determination, encapsulated in the heavy folds of Judas's yellow cloak enveloping Christ.

Other scenes, like the Nativity or the Adoration of the Magi, display a tender humanity. The Flight into Egypt shows figures moving through a rocky landscape with a sense of purpose and weight. Throughout the cycle, Giotto's ability to convey complex narratives and profound emotions through gesture, expression, and composition is unparalleled. The Scrovegni Chapel established a new benchmark for narrative painting, influencing generations of artists. It is also noteworthy that Giotto's friend, the great poet Dante Alighieri, was in Padua during the period Giotto worked there, and some scholars suggest Dante's Divine Comedy may have influenced the depiction of the Last Judgment on the chapel's entrance wall.

Florentine Commissions: Santa Croce and Beyond

Following his triumph in Padua, Giotto returned to Florence as a celebrated master. He undertook significant commissions, including frescoes in the Basilica di Santa Croce, the principal Franciscan church in Florence. He decorated two adjacent chapels for prominent banking families: the Peruzzi Chapel (scenes from the lives of John the Baptist and John the Evangelist) and the Bardi Chapel (scenes from the life of Saint Francis).

Unfortunately, these frescoes suffered considerable damage over the centuries. They were whitewashed in the 18th century and heavily restored after their rediscovery in the 19th century. The Peruzzi Chapel frescoes, executed largely in fresco secco (painting on dry plaster), are particularly compromised. However, even in their damaged state, they reveal Giotto's continued development. The compositions are more complex than those in Padua, with greater attention to architectural detail and spatial arrangement. Figures interact with a sophisticated naturalism, and Giotto continued to explore psychological depth. These works were studied intensely by later Renaissance artists, including Michelangelo, who copied figures from the Peruzzi Chapel.

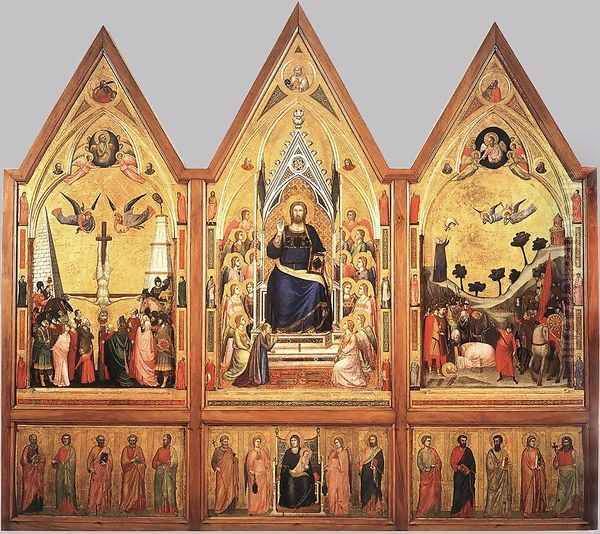

Besides frescoes, Giotto was also a master of panel painting. His most famous panel work is the Ognissanti Madonna (c. 1310), now in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence. This large altarpiece depicts the Virgin Mary enthroned, holding the Christ Child, surrounded by angels and saints. Compared to earlier Madonnas by artists like Cimabue or the Sienese master Duccio di Buoninsegna, Giotto's Virgin is a figure of monumental solidity and maternal warmth. She sits within a convincingly rendered Gothic throne, creating a sense of depth. Her body has weight beneath the drapery, and her gaze engages the viewer directly. This work exemplifies Giotto's ability to imbue traditional religious iconography with a new sense of realism and human presence. Other panel paintings attributed to Giotto or his workshop include the Stefaneschi Triptych for St. Peter's Basilica in Rome and several crucifixes.

Giotto the Architect: The Florence Campanile

Giotto's fame and skill were not limited to painting. In 1334, towards the end of his life, the city of Florence bestowed upon him the prestigious title of Capomaestro (chief architect or master builder) of the Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria del Fiore) and the city's fortifications. His most significant architectural contribution was the design for the cathedral's Campanile (bell tower), now known as "Giotto's Campanile."

Although Giotto died in 1337, only three years after construction began, and the tower was completed by others (including Andrea Pisano and Francesco Talenti) with modifications to his original design, the lower stories reflect his vision. The Campanile is a masterpiece of Florentine Gothic architecture, characterized by its elegant proportions, harmonious geometric divisions, and rich sculptural decoration (the reliefs were executed by Andrea Pisano and later Luca della Robbia and others, possibly based on Giotto's concepts). Giotto's involvement in this major civic project underscores his esteemed position within Florentine society.

Workshop, Followers, and Contemporaries

Like most successful artists of his time, Giotto operated a large and active workshop. Major fresco cycles required numerous assistants to help with plaster preparation, color grinding, and the execution of less critical areas based on the master's designs. While identifying the specific hands of assistants is often difficult, several painters are known to have been closely associated with Giotto or heavily influenced by his style.

Taddeo Gaddi, who Vasari claimed was Giotto's godson and apprentice for 24 years, became a leading Florentine painter in his own right, carrying forward Giotto's narrative clarity and compositional principles, albeit sometimes with a more decorative sensibility (e.g., Baroncelli Chapel frescoes, Santa Croce). Maso di Banco was another highly talented follower, known for his solid figures and strong sense of drama (e.g., Chapel of St. Sylvester, Santa Croce). Other artists like Bernardo Daddi and the anonymous Master of the St. Cecilia Altarpiece also worked within the Giottesque tradition, ensuring that his style dominated Florentine painting for much of the 14th century.

Beyond his students, Giotto interacted with the leading cultural figures of his day. His friendship with Dante Alighieri is well-documented, and both artists shared a common interest in vivid narrative and human emotion. Later writers of the 14th century, such as the poet Petrarch and the author Giovanni Boccaccio, also held Giotto in high esteem. Boccaccio, in his Decameron, praised Giotto for having "brought back to light that art which had for many centuries been buried," remarking that his realism was so convincing it could deceive the viewer's eye. These literary accounts helped cement Giotto's reputation for posterity. While Florence was his main center, he also competed stylistically with Sienese masters like Simone Martini and the Lorenzetti brothers (Pietro and Ambrogio), who developed their own distinct, elegant Gothic style.

Anecdotes and Personality

Vasari and other early commentators paint a picture of Giotto not just as a great artist but also as a man of wit and intelligence. The story of the "O of Giotto" is perhaps the most famous anecdote after the sheep-drawing tale. When a messenger from Pope Benedict XI came seeking samples of Giotto's work to assess his suitability for commissions in Rome, Giotto simply took a brush, dipped it in red paint, and, with a turn of his arm, drew a perfect circle freehand on a piece of paper. He handed this to the astonished messenger, implying that this simple demonstration of perfect control and skill was sufficient proof of his mastery.

Boccaccio also relates tales highlighting Giotto's humor and down-to-earth nature, noting that despite his genius, he was physically plain and not above a good joke. These anecdotes, whether entirely factual or embellished, contribute to the image of Giotto as a fully rounded individual, not just an artistic force – a man whose art was rooted in a keen observation of life and human nature. He lived a relatively calm later life, respected and financially successful, dying in Florence on January 8, 1337. He was buried in the Florence Cathedral with great honor.

The Enduring Legacy: Shaping the Renaissance and Beyond

Giotto's impact on the history of art is immeasurable. He fundamentally shifted the direction of painting away from the symbolic, otherworldly focus of the Byzantine era towards a representation grounded in the observable world and human experience. His innovations laid the essential groundwork for the Italian Renaissance.

His emphasis on volume, weight, and three-dimensional space provided a foundation for the development of linear perspective by later artists like Filippo Brunelleschi and Leon Battista Alberti. His focus on human emotion and psychological depth opened the door for increasingly complex and nuanced depictions of character and narrative. His ability to organize complex scenes into clear, dramatic compositions set a standard for narrative painting.

The generation immediately following Giotto was dominated by his style, disseminated through his workshop and followers like Taddeo Gaddi and Maso di Banco. However, his most profound influence was felt at the dawn of the Quattrocento (15th century). Masaccio, often considered the first truly Renaissance painter, directly built upon Giotto's legacy in his frescoes for the Brancacci Chapel in Florence (c. 1425-1427). Masaccio combined Giotto's sense of monumental form and emotional gravity with the newly developed principles of linear perspective and a more scientific understanding of light, creating figures of unprecedented realism.

Throughout the Renaissance, artists continued to look back to Giotto. Fra Angelico blended Giotto's clarity and piety with Renaissance elegance. Piero della Francesca's solemn, monumental figures echo Giotto's gravity. Even the giants of the High Renaissance acknowledged his importance. Leonardo da Vinci's exploration of human psychology and chiaroscuro owes a debt to Giotto's pioneering work. Michelangelo deeply admired Giotto's powerful figures and sense of drama, famously studying and copying his frescoes in Santa Croce. Raphael absorbed lessons from Giotto's compositional clarity and narrative skill. Giorgio Vasari, in his seminal Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects (1550, revised 1568), firmly established Giotto's position as the progenitor of the Renaissance artistic revival.

Giotto's revolution was not merely technical; it was conceptual. By focusing on the tangible reality of the human form, emotion, and interaction, he placed humanity at the center of his art. He made the divine accessible and relatable, reflecting the burgeoning humanist spirit of his time. He taught artists, and viewers, to see the world, and the stories of their faith, with new eyes.

Conclusion: The Dawn Personified

Giotto di Bondone (c. 1267–1337) was more than just a painter and architect; he was a visionary who stood at the cusp of two worlds, the medieval and the Renaissance. With his feet planted firmly in the traditions of his time, he possessed the genius to look beyond them, drawing inspiration directly from nature and human life. His revolutionary approach to form, space, and emotion shattered the conventions of Byzantine art and forged a new path for visual representation in Europe. From the debated frescoes of Assisi to the undisputed mastery of the Scrovegni Chapel and the influential works in Florence, Giotto's art consistently speaks with clarity, power, and profound humanity. His legacy is not merely contained within his surviving works but lives on in the very foundations of Renaissance art and the continuing tradition of realism and humanism in Western painting. He truly was the dawn of a new era in art.