Giuseppe Bazzani stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the vibrant tapestry of eighteenth-century Italian art. Born in Mantua in 1690 and dying in the same city in 1769, his life and career were deeply intertwined with this historic Lombardian center. Operating during the transition from the grandeur of the High Baroque to the lighter, more intimate Rococo, Bazzani forged a distinctive style characterized by dynamic compositions, emotive figures, and a remarkable sensitivity to light and color. His work, primarily religious and mythological scenes for churches, monasteries, and private patrons, reveals an artist who absorbed diverse influences yet developed a uniquely personal artistic voice.

Early Life and Formative Influences in Mantua

Giuseppe Bazzani's artistic journey began in Mantua, a city with a rich artistic legacy, having been a major center of the Renaissance under the Gonzaga dukes, who patronized artists like Andrea Mantegna and Giulio Romano. Though the political and economic power of Mantua had waned by the 18th century, it remained a place where artistic traditions were valued. Bazzani's initial training was under the Parmesan painter Giovanni Canti (1653–1716). Canti, active in Mantua, would have introduced the young Bazzani to the traditions of Emilian painting, known for its grace and soft sfumato, stemming from masters like Correggio and Parmigianino.

Beyond his formal tutelage, Bazzani was a keen student of the great masters whose works he could have encountered directly or through prints. The profound impact of the Renaissance titan Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431–1506), who had spent much of his career in Mantua, is discernible in Bazzani's attention to anatomical precision and perspectival construction, particularly in his earlier works. The opulent color palettes and grand narrative compositions of Paolo Veronese (1528–1588), a luminary of the Venetian school, also left an indelible mark on Bazzani, inspiring a richness of hue and a theatrical flair. Furthermore, the dynamic energy, dramatic lighting, and sensuous figures of the Flemish Baroque master Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) resonated deeply with Bazzani, influencing his sense of movement and compositional vigor. These diverse influences provided a fertile ground from which Bazzani's own style would blossom.

The Development of a Personal Style: From Baroque to Rococo

As Bazzani matured, his artistic language evolved, absorbing contemporary trends while retaining a personal stamp. He moved beyond the more robust forms of his early influences towards a style that embraced the elegance and vivacity of the burgeoning Rococo. His brushwork became looser and more spirited, his figures often imbued with a nervous energy and a heightened emotionalism. This shift is evident in the flickering light and agitated surfaces that characterize many of his mature paintings.

Art historians have noted Bazzani's assimilation of various regional Italian schools. The dramatic intensity and sometimes somber palette of Ligurian painters, such as Alessandro Magnasco (1667–1749), known for his rapid, sketchy brushwork and scenes of monks, soldiers, and everyday life imbued with a sense of unease, can be felt in certain aspects of Bazzani's work. Magnasco's "pittura di tocco" (painting of touch) and his often unconventional, elongated figures find echoes in Bazzani's more expressive moments.

The influence of the Venetian school, then at its zenith with figures like Giovanni Battista Tiepolo (1696–1770), Giovanni Battista Pittoni (1687–1767), and the Guardi brothers, Francesco (1712–1793) and Gianantonio (1699–1760), is also palpable. Bazzani shared with these Venetian contemporaries a love for luminous color, dynamic compositions, and a certain theatricality. The lightness of touch and delicate sensibility often associated with Pittoni, or the atmospheric qualities of Francesco Guardi, can be seen as kindred spirits to Bazzani's evolving Rococo tendencies. Sebastiano Ricci (1659–1734), an earlier Venetian who played a crucial role in disseminating a lighter, more decorative style, also forms part of this influential artistic milieu.

Some scholars, like Nicola Ivanoff, have even pointed to "expressionist tendencies" in Bazzani's art, an anachronistic term but one that captures the intense emotional charge and the sometimes unconventional rendering of form in his paintings. This suggests an artist less concerned with academic polish and more focused on conveying the psychological or spiritual essence of his subjects. His style was described as becoming more "exotic" over time, perhaps indicating a departure from purely Italianate models and an openness to broader European currents, including influences from the Austrian school, given Mantua's political connections to the Habsburg Empire. Artists like Paul Troger (1698–1762) or Franz Anton Maulbertsch (1724–1796) were developing a highly expressive and dynamic form of late Baroque in Central Europe.

Major Themes and Representative Works

Bazzani's oeuvre is dominated by religious subjects, including numerous altarpieces and devotional paintings for churches and monastic orders in Mantua and its surrounding region. He also executed mythological scenes and some portraits, showcasing his versatility. His works are characterized by their dramatic compositions, often employing diagonals and swirling movement to engage the viewer.

One of his most celebrated works is The Dream of Saint Romuald. This subject, famously depicted by Andrea Sacchi, shows the founder of the Camaldolese order dreaming of his monks ascending to Heaven. Bazzani’s interpretation would likely emphasize the visionary quality of the scene, using flickering light and dynamic figures to convey the spiritual intensity of the dream. While the user's text mentions The Dream of St. Romanus, St. Romuald is a more common subject for such visionary depictions in Italian art, and Bazzani is indeed credited with paintings of St. Romuald.

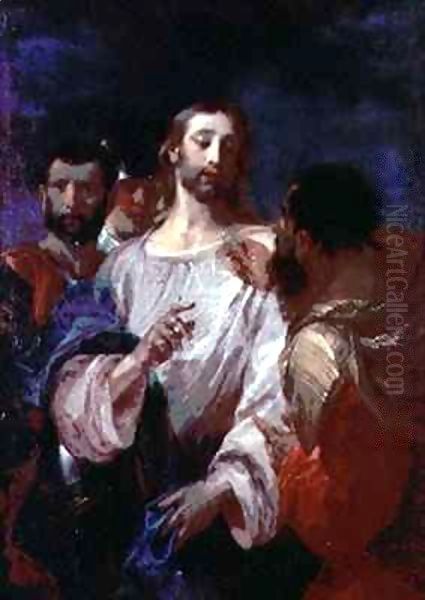

The Incredulity of St. Thomas is another significant religious work. This theme, depicting Christ inviting Thomas to touch his wounds, offered Bazzani an opportunity to explore profound human emotion and divine revelation. His rendition would likely focus on the dramatic interplay between the figures, the contrasting expressions of doubt and gentle reassurance, all articulated through his characteristic energetic brushwork and mastery of chiaroscuro.

The Tribute Money, a version of which is housed in the MacKenzie Art Gallery in Regina, Canada, tackles a well-known Gospel scene. Christ's instruction to "render unto Caesar what is Caesar's, and unto God what is God's" is a moment rich in theological and political implication. Bazzani's treatment would likely capture the gravity of the moment, the varied reactions of the apostles, and the central, authoritative figure of Christ, all animated by his fluid style.

The painting The Departure of the Prodigal Son, located in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art (formerly William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art) in Kansas City, USA, demonstrates Bazzani's skill in narrative painting. The emotional farewell, the anticipation of the journey, and the underlying themes of rebellion and eventual redemption are all elements Bazzani would have explored with sensitivity. His use of light and shadow would enhance the pathos of the scene, highlighting the expressions and gestures of the characters.

Another notable work, The Ecstasy of Saint Margaret of Cortona, found in the Palazzo d'Arco in Mantua, exemplifies Bazzani's ability to depict intense spiritual experiences. Saint Margaret's mystical communion with the divine would be rendered with a fervor characteristic of Baroque religious art, yet softened by Rococo elegance. The swirling draperies, agitated figures, and ethereal light would combine to create a powerful image of spiritual transport.

Throughout these works, Bazzani's distinctive handling of paint is evident. He often employed rapid, broken brushstrokes, creating a vibrant surface texture that catches the light. His color palettes could range from rich, sonorous tones to lighter, more pastel shades, depending on the subject and desired mood. His figures, while anatomically sound, often possess an elongated grace and an expressive dynamism that are hallmarks of his style.

Bazzani in the Mantuan Art World: The Academy and Collaborations

Giuseppe Bazzani was not an isolated figure but an active participant in the artistic life of Mantua. His talent and dedication earned him considerable respect, culminating in his appointment as director of the Accademia di Belle Arti (Academy of Fine Arts) in Mantua in 1767, a position he held until his death. This role signifies his standing as a leading artist in the city and his commitment to the education of younger painters. The Academy would have been a center for artistic discourse and the dissemination of prevailing styles, and Bazzani's leadership would have shaped its direction in his later years.

The provided information mentions a collaboration with Francesco Maria Rinaldi on frescoes in Mantuan churches and monasteries. Such collaborations were common, especially for large-scale decorative projects. Rinaldi, likely a local contemporary, would have worked alongside Bazzani, perhaps dividing labor based on specific skills or areas of the composition. These fresco projects, often adorning ceilings and walls, would have allowed Bazzani to work on an expansive scale, further showcasing his compositional abilities and his command of perspective and foreshortening.

The artistic environment of Mantua, while perhaps not as globally influential as Venice or Rome at this time, still fostered local talent. Bazzani's presence would have been significant for other Mantuan artists. His style, blending Lombard traditions with broader Italian and European currents, would have offered a compelling model. He was a contemporary of other Italian painters who, while perhaps working in different regional centers, contributed to the overall artistic climate of the 18th century. These include figures like the Neapolitan masters Francesco Solimena (1657–1747) and Francesco de Mura (1696–1782), whose late Baroque and Rococo works were highly influential in Southern Italy. In Rome, Pompeo Batoni (1708–1787) was a leading figure, transitioning towards Neoclassicism, while Corrado Giaquinto (1703–1766) produced spectacular Rococo decorations. In Northern Italy, besides the Venetians, artists like Fra Galgario (Vittore Ghislandi, 1655–1743) in Bergamo created strikingly realistic portraits, and Giambettino Cignaroli (1706–1770) in Verona upheld a more classical tradition. Antonio Balestra (1666-1740), also from Verona, was an important late Baroque painter whose influence extended to younger artists.

Later Career, Legacy, and Critical Reception

Bazzani's later career was marked by his prestigious role at the Mantuan Academy and continued productivity. His style in these later years likely consolidated the Rococo tendencies, emphasizing elegance, movement, and a lighter touch, though without sacrificing the emotional depth that often characterized his work. The "exotic" quality noted by some critics might refer to a heightened sense of fantasy or a more decorative approach in his later paintings.

Despite his local prominence and a body of work that is both substantial and artistically compelling, Giuseppe Bazzani has not always received the widespread international recognition of some of his more famous contemporaries, like Tiepolo or Canaletto. This is partly due to his career being largely centered in Mantua, away from the major artistic hubs of Venice, Rome, or Naples, which attracted more international patrons and travelers. However, his work has been increasingly appreciated by scholars and connoisseurs of Italian Baroque and Rococo art.

Modern art historical research, including the work of scholars like Nicola Ivanoff mentioned in the provided texts, has helped to re-evaluate Bazzani's contribution. Ivanoff's identification of "expressionist tendencies" highlights a particular facet of Bazzani's art that distinguishes him – a willingness to prioritize emotional impact, sometimes through less conventional means. This suggests an artist who, while working within established traditions, was not afraid to push boundaries in pursuit of expressive power.

His paintings are now found in various museums and collections beyond Mantua, indicating a growing appreciation for his unique talents. Besides the aforementioned works in Kansas City and Regina, and the holdings in Mantua's Palazzo d'Arco, institutions like the Uffizi Gallery in Florence are also noted as holding his works, though specific pieces are not detailed in the provided text. The presence of his art in international collections allows for a broader audience to engage with his distinctive vision.

Bazzani's legacy lies in his successful fusion of diverse artistic influences into a coherent and personal style. He navigated the transition from the gravitas of the late Baroque to the spirited elegance of the Rococo with skill and originality. His paintings, with their dynamic compositions, emotive figures, and masterful use of light and color, represent a significant contribution to North Italian painting in the 18th century. He stands as a testament to the enduring artistic vitality of regional centers like Mantua, even as artistic power dynamics shifted across Europe.

Conclusion: An Enduring Mantuan Voice

Giuseppe Bazzani was an artist of considerable talent and individuality. Rooted in the rich artistic soil of Mantua, he looked to the giants of the past like Mantegna, Veronese, and Rubens, while simultaneously engaging with the contemporary currents of the Rococo, absorbing influences from Venice, Liguria, and perhaps even beyond. His work is characterized by a vibrant energy, a deep emotional resonance, and a distinctive handling of paint that makes his canvases come alive with flickering light and movement.

As a painter of religious and mythological subjects, and as the esteemed director of the Mantuan Academy of Fine Arts, Bazzani played a crucial role in the artistic life of his city. While perhaps not achieving the global fame of some of his peers, his oeuvre remains a compelling testament to the artistic richness of 18th-century Italy. His paintings, with their blend of Baroque drama and Rococo grace, continue to captivate viewers and offer a unique window into the artistic sensibilities of his time. Giuseppe Bazzani deserves recognition as a master whose distinctive voice contributed significantly to the diverse chorus of Italian art. His ability to synthesize tradition and innovation, and to imbue his works with genuine feeling, secures his place as an important figure in the history of European painting.