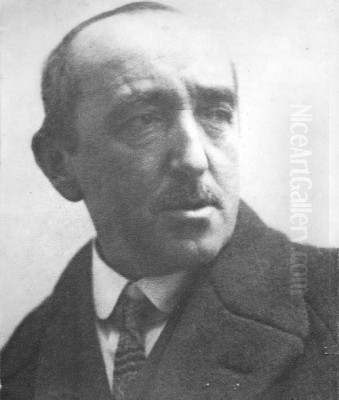

Plinio Nomellini stands as a significant figure in Italian art history, navigating the vibrant and often turbulent currents of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Born in Livorno in 1866 and passing away in Florence in 1943, his life and career spanned a period of profound artistic and social transformation in Italy. Nomellini was not merely a painter; he was an active participant in the cultural dialogues of his time, transitioning from the lingering influences of Realism to become a leading exponent of Italian Divisionism and Symbolism. His work is characterized by a distinctive use of colour and light, a deep engagement with both landscape and social themes, and a complex relationship with the political ideologies that shaped his era. This exploration delves into the multifaceted career of Plinio Nomellini, examining his artistic development, key influences, representative works, interactions with contemporaries, and his enduring, albeit sometimes contested, legacy.

Early Life and Florentine Formation

Plinio Nomellini's artistic journey began in Livorno, a bustling port city on the Tyrrhenian coast, known for its cosmopolitan atmosphere and its connection to the Macchiaioli movement. Born into a family involved in customs administration, his early environment likely exposed him to diverse influences. However, his formal artistic training commenced in 1885 when he enrolled at the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts in Florence. This move placed him at the heart of Tuscan artistic traditions and, crucially, under the tutelage of Giovanni Fattori, one of the most prominent figures of the Macchiaioli school.

The Macchiaioli, often considered precursors to French Impressionism, emphasized painting outdoors (en plein air) and capturing the effects of light and shadow through distinct "patches" or "stains" (macchie) of colour. Fattori's influence was profound, instilling in Nomellini a strong foundation in drawing, a sensitivity to light, and an interest in depicting scenes of everyday life and the Tuscan landscape. During his time at the Academy, Nomellini also formed important connections with other key figures associated with the Macchiaioli and late Italian Realism, including the influential critic and painter Telemaco Signorini and the master of intimate domestic scenes, Silvestro Lega. These interactions immersed him in the prevailing artistic debates and techniques of the time.

Nomellini quickly demonstrated his talent, exhibiting his work as early as 1886 at the Florentine Promotrice. His early paintings reflected the Macchiaioli concern for realism and the honest depiction of Tuscan life and landscapes. Works from this period often show a robust handling of paint and a keen observation of natural light, laying the groundwork for his later explorations into colour theory. The Florentine environment, rich with artistic heritage yet receptive to new ideas, provided the fertile ground upon which Nomellini's distinct artistic personality began to take shape.

The Move to Genoa and the Embrace of Divisionism

A pivotal moment in Nomellini's career occurred after his participation in the Paris World Exposition of 1889. Inspired perhaps by the international artistic currents he encountered there, and seeking new environments, he relocated to Genoa in 1890. This move marked a significant stylistic shift. While maintaining his connection to landscape and social observation, Nomellini began to move away from the broader patches of the Macchiaioli towards the more systematic application of colour characteristic of Divisionism.

Divisionism, the Italian response to French Neo-Impressionism (or Pointillism, associated with Georges Seurat and Paul Signac), was based on scientific theories of optics and colour perception. Instead of mixing colours on the palette, Divisionist painters applied small dots or filaments of pure colour directly onto the canvas, intending for them to blend optically in the viewer's eye. This technique aimed to achieve greater luminosity and vibrancy than traditional methods allowed. Nomellini became one of the leading figures of this movement in Italy.

In Genoa, Nomellini connected with other artists exploring similar paths and engaged with the city's vibrant, sometimes radical, intellectual and political life. His technique evolved rapidly during the 1890s. He adopted the filament-like brushstrokes characteristic of Italian Divisionism, using juxtaposed strands of pure colour to build forms and, most importantly, to capture the shimmering effects of Mediterranean light. His palette became brighter, his handling of paint more dynamic, creating surfaces that pulsed with energy and luminosity. This technical shift allowed him to explore themes of labour, social reality, and the power of nature with a new intensity.

His interactions during this period were crucial. He established contact with Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, another central figure of Italian Divisionism, known for his monumental social realist works like The Fourth Estate. Their dialogue, documented through correspondence, reveals a shared interest in the technical and expressive possibilities of the Divisionist method. Nomellini also connected with the influential art critic and dealer Vittorio Grubicy de Dragon and his brother Alberto Grubicy, who were instrumental in promoting Divisionism in Italy. These connections placed Nomellini at the forefront of the Italian avant-garde.

Anarchism, Imprisonment, and Artistic Evolution

Nomellini's time in Genoa was not solely defined by artistic experimentation; it was also marked by intense political engagement. He became deeply involved in the city's burgeoning anarchist movement, associating with radical thinkers and activists. This period saw increasing social unrest and government crackdowns on dissent across Italy. Nomellini's political activities led to his arrest in 1894 on charges related to anarchism. He spent several months imprisoned in the Sant'Andrea jail before ultimately being tried and acquitted.

This experience of imprisonment profoundly impacted Nomellini, both personally and artistically. While it solidified his commitment to social justice, it also seems to have catalyzed a further evolution in his art, pushing him towards more symbolic and allegorical modes of expression. Direct social critique, as seen in works like Piazza del Carico (Loading Square), which depicted the harsh realities of dockworkers' lives using Divisionist techniques, began to merge with a more lyrical and evocative approach.

The confinement likely provided time for introspection, potentially leading him to explore themes beyond immediate social observation. The turn towards Symbolism, already nascent in the intellectual currents of the late nineteenth century, offered a means to convey deeper emotional states, universal ideas, and spiritual concerns. His Divisionist technique, with its emphasis on light and dematerialized form, proved remarkably adaptable to these new expressive goals, allowing him to create works that were both visually dazzling and emotionally resonant. The experience underscored the inseparable link between his life, his political convictions, and his artistic output.

Symbolism and National Recognition

Following his release and the turn of the century, Nomellini fully embraced Symbolism, becoming one of its most original interpreters within the Italian context. While continuing to employ his refined Divisionist technique, his subject matter increasingly shifted towards evocative landscapes, mythological themes, and allegorical representations of nature and human emotion. He sought to capture not just the appearance of the world, but its underlying spirit and poetry.

His work from this period often features luminous, dreamlike atmospheres. Sinfonia della Luna (Moonlight Symphony), exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1899 and subsequently purchased for the Ca' Pesaro Gallery of Modern Art, is a prime example. This painting uses the Divisionist technique to render the ethereal effects of moonlight on the sea, creating a powerful sense of mystery and natural harmony. It demonstrates a move away from objective representation towards a more subjective and musical interpretation of nature, influenced perhaps by German Symbolism and the broader European movement.

Nomellini became a regular participant in major exhibitions, most notably the Venice Biennale. His presence was particularly felt in the 1907 Biennale's "Sala del Sogno" (Room of Dream), a space dedicated to Symbolist and imaginative art, where his works were shown alongside those of other key figures exploring visionary themes. This period also saw the deepening of his friendship with the renowned opera composer Giacomo Puccini. Nomellini spent time near Puccini's home in Torre del Lago, and the evocative, light-filled landscapes of the Versilia coast became a recurring motif in his paintings, often imbued with a lyrical, almost musical quality. He even established a studio on the island of Elba, further dedicating himself to capturing the unique light and atmosphere of the Mediterranean landscape through a Symbolist lens. Works like Polifonia sought to visually represent the harmony and energy of nature, using dynamic, vibrant brushwork.

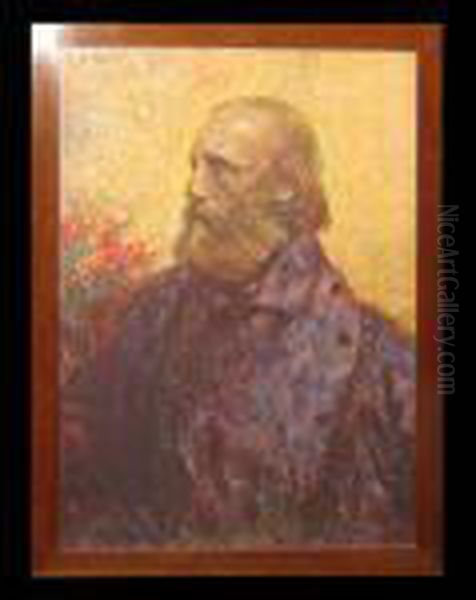

The Height of Fame and the Icon of Garibaldi

The first two decades of the twentieth century marked the zenith of Nomellini's fame and influence. He was widely regarded as one of Italy's leading contemporary painters, celebrated for his technical mastery and his ability to synthesize modern techniques with national themes. His Divisionist style, now fully matured and infused with Symbolist sensibility, was highly sought after.

Perhaps the single work that best encapsulates his national prominence during this era is Garibaldi. While versions exist, the iconic image often associated with him likely dates from around 1906-1907. Depicting the revered hero of the Risorgimento, Giuseppe Garibaldi, often in a heroic, almost mythical light, the painting resonated deeply with Italian national sentiment. Its widespread reproduction and distribution, particularly during the "Maggio Radioso" (Radiant May) of 1915 – a period of fervent nationalist campaigning for Italy's entry into World War I – transformed it into a popular icon. The painting exemplified Nomellini's ability to harness the visual power of Divisionism for subjects of historical and national significance, rendering Garibaldi not just as a historical figure but as a radiant symbol of Italian unity and spirit.

During this period, Nomellini continued to produce significant works, including portraits and landscapes. Sorella (Sister), depicting a young girl, showcases his ability to combine intimate observation with his characteristic luminous technique. He remained connected to artistic circles, particularly in Tuscany and Liguria. His interactions with artists like Raffael Gambogi, the Welsh painter Llewellyn Lloyd (who settled in Tuscany), and the Ligurian Ruberto Merello, reflect a continued engagement with landscape painting and the specific qualities of Mediterranean light and colour. He also maintained connections with figures from his earlier Genoese period, such as Gian Battista Bellardi. His work was frequently exhibited alongside other major Italian artists of the time, including fellow Divisionists and Symbolists like Gaetano Previati, Angelo Morbelli, and the Alpine painter Giovanni Segantini, solidifying his position within the complex tapestry of early 20th-century Italian art.

Later Years, Fascism, and Contested Legacy

The later part of Nomellini's career unfolded against the backdrop of rising Fascism in Italy. Like many artists and intellectuals of his generation, Nomellini's relationship with the Fascist regime was complex and has been subject to considerable historical debate. Having moved from youthful anarchism towards nationalism (evident in works like Garibaldi), he found some common ground with aspects of Fascist ideology, particularly its emphasis on national identity and Roman heritage. He received commissions from the regime and participated in state-sponsored exhibitions during the 1920s and 1930s.

However, it is crucial to note that Nomellini's art never fully conformed to the rigid, neoclassical aesthetics often promoted by the Fascist cultural establishment. His deeply ingrained Divisionist technique and Symbolist inclinations, with their emphasis on light, colour, and subjective experience, remained distinct from the more propagandistic or academically classical styles favoured by some within the regime. His adherence to his personal style, even while navigating the political landscape, suggests a degree of artistic independence.

Nevertheless, his association with Fascism, however complex or perhaps opportunistic, cast a long shadow over his posthumous reputation. After World War II and the fall of Fascism, artists associated with the regime were often viewed critically or marginalized by the new cultural and political order. Nomellini, despite his significant contributions to Italian modernism, suffered a period of relative neglect in academic and critical circles. His earlier anarchist past seemed overshadowed by his later compromises. He continued to paint until his death in Florence in 1943, leaving behind a body of work marked by extraordinary technical skill but also by the intricate and often contradictory political currents of his time.

Artistic Style Revisited: Light, Colour, and Meaning

Plinio Nomellini's artistic style is a fascinating synthesis of major late 19th and early 20th-century currents, filtered through his unique sensibility. His journey began with the solid grounding of the Macchiaioli, evident in his early attention to realism and the effects of natural light captured through distinct colour patches. His crucial adoption of Divisionism transformed his approach, allowing him to achieve unprecedented levels of luminosity and vibrancy. Unlike the more pointillist approach of Seurat, Nomellini, like many Italian Divisionists, favoured elongated, filament-like brushstrokes that created a dynamic, shimmering texture on the canvas.

Colour was paramount for Nomellini. He used pure hues, juxtaposed according to optical principles, to construct form, convey atmosphere, and evoke emotion. His mastery of light, particularly the intense sunlight of the Mediterranean, is a defining characteristic of his work. Whether depicting bustling ports, tranquil landscapes, or symbolic allegories, light is often an active protagonist, dissolving forms and creating dazzling visual effects.

The transition to Symbolism added another layer to his art. While the Divisionist technique remained his primary tool, the purpose shifted. He moved beyond mere optical representation to explore subjective states, mythological narratives, and the spiritual dimensions of nature. His landscapes became imbued with mood and meaning, often possessing a dreamlike or lyrical quality. Even his portraits and depictions of historical figures like Garibaldi are elevated beyond simple likenesses, becoming radiant icons charged with symbolic energy. His ability to blend advanced technique with profound thematic content marks him as a major figure in the Italian Symbolist movement.

Influence and Historical Position

Plinio Nomellini occupies a significant, if sometimes overlooked, position in the history of Italian modern art. He served as a crucial bridge figure, absorbing the lessons of the Macchiaioli and transmitting them into the new language of Divisionism. He was undeniably one of the leading exponents of Italian Divisionism, standing alongside figures like Pellizza da Volpedo, Previati, Segantini, and Morbelli. His technical brilliance and innovative use of colour contributed significantly to the movement's development and recognition.

His embrace of Symbolism further broadened his impact, placing him within a European-wide trend that sought to move art beyond realism towards subjective and spiritual expression. His unique fusion of Divisionist technique with Symbolist themes created a distinctive body of work that captured both the sensory experience of light and colour and the deeper emotional and intellectual currents of the era. His influence extended through his participation in major exhibitions like the Venice Biennale and through his interactions with a wide network of artists and intellectuals.

However, his legacy remains complex due to his later political associations. The post-war tendency to marginalize artists linked to Fascism meant that Nomellini's contributions were sometimes downplayed compared to contemporaries with less complicated political histories. Recent scholarship has sought to re-evaluate his work more objectively, acknowledging the political complexities while reaffirming his artistic importance. He is increasingly recognized for his technical mastery, his role in advancing Italian painting beyond nineteenth-century realism, and his creation of visually stunning works that continue to resonate with viewers.

Conclusion: An Enduring Radiance

Plinio Nomellini's life and art encapsulate the dynamism and contradictions of Italy during a period of intense change. From his roots in the Macchiaioli tradition to his pioneering role in Divisionism and his evocative explorations of Symbolism, he consistently pushed the boundaries of his craft. His paintings are characterized by an extraordinary sensitivity to light and colour, rendered through a meticulous yet vibrant technique. He tackled a wide range of subjects, from the sun-drenched landscapes of Tuscany and Liguria to scenes of social commentary and powerful national symbols like Garibaldi.

While his political journey adds a layer of complexity to his biography, it does not diminish the visual power and historical significance of his artistic achievements. Nomellini mastered the science of colour to create works of profound sensory impact, capable of conveying both the tangible reality of the world and the intangible realms of emotion and symbol. His paintings, pulsating with light and energy, stand as a testament to a pivotal moment in Italian art, securing Plinio Nomellini's place as a key figure whose work continues to reward close attention and appreciation. His art remains a symphony of light and shadow, reflecting the complex beauty of his time.