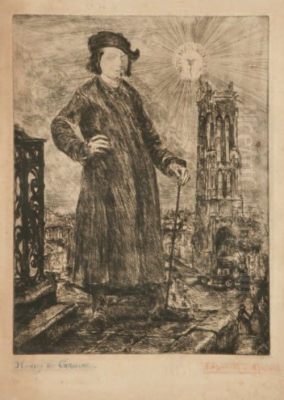

Henry de Groux, a name that resonates with the tumultuous spirit of late 19th and early 20th-century European art, stands as a formidable figure within the Symbolist movement. A painter, sculptor, and printmaker of considerable power and vision, de Groux carved a unique path, often marked by controversy and intense personal conviction. His life and work offer a compelling insight into an era of artistic ferment, societal upheaval, and profound psychological exploration. Born into an artistic lineage and thrust into the vibrant, often contentious, art scenes of Brussels and Paris, de Groux produced a body of work characterized by its dramatic intensity, historical and mythological scope, and deeply personal symbolism.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Henry Jules Charles de Groux was born in Brussels on November 16, 1866. He was the son of Charles Corneille Auguste de Groux, a respected painter known for his realistic depictions of peasant life and social concerns. The elder de Groux was a significant figure in Belgian art, associated with the Société Libre des Beaux-Arts, and his influence, though perhaps not stylistically direct, undoubtedly provided an early immersion in the world of art for his son. Growing up in an environment where artistic creation was central likely shaped Henry's ambitions and sensibilities from a young age.

His formal artistic training commenced at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. This institution, like many academies of its time, would have provided a grounding in traditional techniques, drawing from the figure, and the study of Old Masters. However, de Groux's temperament was not one to be long confined by academic convention. Even during his formative years, he began to seek out mentors and influences that resonated more with his burgeoning individualistic and expressive tendencies.

Among those he sought advice from were figures like the sculptor and painter Constant Meunier, whose powerful depictions of industrial laborers carried a profound social weight. Félicien Rops, notorious for his decadent and erotically charged Symbolist works, and the more introspective Symbolist painter Xavier Mellery, known for his "L'âme des choses" (The Soul of Things) series, also played roles in his development. Alfred Stevens, a Belgian painter who achieved great success in Paris with his elegant portrayals of modern women, represented a different facet of the artistic world, yet de Groux's engagement with such diverse figures indicates a broad curiosity and a desire to forge his own artistic language.

The Tumultuous Years with Les XX

The late 19th century in Brussels was a hotbed of avant-garde activity, and central to this was the artistic group known as "Les XX" (The Twenty), founded in 1883 by Octave Maus. Les XX was an invitation-only group dedicated to promoting new and radical art, organizing annual exhibitions that showcased international artists alongside its Belgian members. It became a crucial platform for Impressionism, Neo-Impressionism, and Symbolism in Belgium, introducing works by artists like Georges Seurat, Paul Gauguin, and Vincent van Gogh to the Belgian public.

Henry de Groux was invited to join Les XX in 1886 and officially became a member in 1887. This was a significant recognition of his emerging talent and alignment with progressive artistic currents. He exhibited with the group, and his early works began to show the dramatic flair and ambitious scale that would characterize his mature style. However, his tenure with Les XX was to be short-lived and marked by a famous controversy.

In 1890, at the annual exhibition of Les XX, a dispute arose concerning the inclusion of works by Vincent van Gogh. De Groux reportedly took offense at Van Gogh's paintings, considering them unworthy of being shown alongside his own. Accounts suggest he vehemently protested their exhibition. This stance put him at odds with other members of Les XX, including Paul Signac, who defended Van Gogh. The disagreement escalated, and de Groux either resigned or was expelled from the group. This incident highlighted de Groux's often uncompromising and fiery temperament, a trait that would surface repeatedly throughout his career. Despite this break, his association with Les XX had placed him firmly within the avant-garde milieu.

The Monumental Vision: Christ aux Outrages

Perhaps the most defining work of Henry de Groux's career, and certainly his most famous, is the monumental painting Le Christ aux Outrages (The Mocking of Christ, or Christ Scorned). Created between 1888 and 1889, this vast canvas, measuring approximately 3 by 4 meters, is a powerful and harrowing depiction of Christ being tormented by a frenzied mob. It is a work that encapsulates many of the core tenets of Symbolism: a focus on subjective experience, emotional intensity, and the use of traditional subject matter to explore contemporary anxieties and universal themes.

In Christ aux Outrages, de Groux presents a chaotic, swirling vortex of figures. Christ, isolated and luminous amidst the darkness, endures the jeers, blows, and spittle of a grotesque and varied crowd. The figures in the mob are not merely historical representations but seem to embody a timeless human capacity for cruelty and ignorance. Their faces are contorted, almost bestial, reflecting a raw, unbridled aggression. De Groux's handling of paint is vigorous and expressive, contributing to the painting's visceral impact. The dramatic use of chiaroscuro, with Christ as the focal point of light, recalls Baroque masters like Caravaggio, yet the psychological intensity and the almost nightmarish quality of the scene are distinctly modern.

The painting was a sensation. When it was rejected by the Salon in Brussels, de Groux arranged for it to be exhibited independently, where it drew large crowds and considerable critical attention, both positive and negative. Its scale, ambition, and emotional force were undeniable. Christ aux Outrages became a landmark of Belgian Symbolism, comparable in its impact to James Ensor's Christ's Entry into Brussels in 1889. Ensor, another key figure in Belgian modernism and a fellow member of Les XX (though their relationship was complex), also used religious iconography for social critique and personal expression, often with a similarly grotesque and satirical edge. De Groux's work, however, tended towards a more tragic and heroic vision. Christ aux Outrages cemented his reputation as an artist of immense power and uncompromising vision. The work is now housed in the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels.

Parisian Life: Art, Literature, and Turmoil

Following his break with Les XX and seeking a larger stage for his ambitions, Henry de Groux moved to Paris in the early 1890s. Paris was then the undisputed capital of the art world, a melting pot of artistic innovation and intellectual debate. De Groux quickly immersed himself in its vibrant cultural life, establishing connections with a wide array of artists and writers.

His studio became a meeting place, and he formed friendships with prominent figures. Among them was the celebrated novelist Émile Zola. Their bond became particularly strong during the Dreyfus Affair, a political scandal that deeply divided French society. Zola's famous open letter "J'Accuse…!" in defense of Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish army officer falsely accused of treason, put Zola himself at great personal risk. De Groux, a staunch supporter of Dreyfus and Zola, reportedly acted as Zola's bodyguard during this tumultuous period, a testament to his loyalty and perhaps his own combative spirit.

De Groux's circle in Paris included other luminaries. He knew the Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin, whose search for the primitive and symbolic resonated with certain aspects of de Groux's own artistic explorations. He was acquainted with Auguste Rodin, the revolutionary sculptor whose expressive power and psychological depth paralleled de Groux's aims in painting. Contacts also included Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, chronicler of Parisian nightlife; James Abbott McNeill Whistler, the American expatriate painter known for his aestheticism; and the Belgian Symbolist poet Émile Verhaeren. The influential Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé was another figure within his orbit.

He also maintained connections with fellow Belgian artists, such as William Degouve de Nuncques, with whom he had shared a studio in Brussels during the early 1880s. Degouve de Nuncques was known for his mysterious and atmospheric Symbolist landscapes. In Paris, de Groux formed a close friendship with the French artist Émile Baru and exhibited alongside him. His network extended to figures like the printmaker Louis-Philibert Debucourt, and he was part of a milieu that included Jean Cocteau (though the provided text mentions "Jules Cocteau," Jean is the far more prominent artistic figure of the era and a likely association).

De Groux exhibited his work in various Parisian Salons and galleries. He showed at the Salon des Champs-de-Mars (organized by the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, a more progressive alternative to the official Salon) in 1890. His works were also seen at avant-garde venues like the gallery of Le Barc de Boutteville, which hosted many Symbolist and Nabis painters, and at exhibitions organized by La Plume, a literary and artistic review. He participated in exhibitions of the Union Libérale des Artistes Français and had a significant solo exhibition at the prestigious Galerie Georges Petit in 1901. These activities solidified his presence in the Parisian art scene, even if his uncompromising nature sometimes made relationships difficult.

Artistic Style: Symbolism, History, and Expression

Henry de Groux's artistic style is firmly rooted in Symbolism, but it incorporates elements that give it a unique character. Symbolism, as a movement, rejected the purely objective representation of Naturalism and Impressionism, seeking instead to evoke ideas, emotions, and subjective states of mind through suggestive imagery, metaphor, and allegory. De Groux embraced this ethos wholeheartedly.

His thematic concerns were often grand and epic. He was drawn to religious subjects, as seen in Christ aux Outrages, but also to mythology, history, and literature. Works like The Fall of Troy, The Death of Siegfried (drawing from Wagnerian opera and Germanic myth, popular Symbolist sources), and Dante and Virgil in Hell demonstrate his ambition to tackle universal themes of heroism, tragedy, suffering, and the human condition. These subjects allowed him to explore intense emotional states and dramatic narratives.

While a Symbolist, de Groux's work often retained a powerful sense of physicality and realism in the rendering of figures, even when distorted for expressive effect. This might reflect the influence of his father's social realism or his academic training. However, this realism was always subservient to the symbolic and emotional content of the work. His compositions are often dynamic and crowded, filled with swirling movement and dramatic gestures, reminiscent of Baroque masters but infused with a modern psychological tension.

The influence of earlier Romantic painters, particularly Eugène Delacroix, is palpable in de Groux's work, especially in his use of color and dynamic composition. Delacroix's dramatic historical and literary scenes, his rich palette, and his emphasis on emotional expression provided a powerful precedent for artists like de Groux who sought to create art of great passion and imaginative scope.

Beyond painting, de Groux was also a sculptor and a prolific printmaker. His sculptures, though less numerous than his paintings, often carried the same dramatic intensity. His prints, particularly his lithographs, allowed for a wider dissemination of his imagery and explored similar themes. Works like the print series Les Errants (The Wanderers) showcase his skill in this medium and his continued preoccupation with themes of suffering and displacement.

The Horrors of War and Later Years

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 profoundly affected Henry de Groux. Like many artists of his generation, he was compelled to respond to the unprecedented brutality and scale of the conflict. He created a series of works depicting the horrors of the war, focusing on the suffering of soldiers and civilians. These paintings and drawings are stark and unflinching, conveying the grim reality of trench warfare, bombardments, and the psychological toll of the conflict. Titles like The Enemy is Coming evoke the fear and chaos of war. His war art stands as a powerful testament to the human cost of the Great War, aligning him with other artists who documented its horrors, such as Otto Dix or Käthe Kollwitz, though de Groux's style remained rooted in his particular brand of dramatic Symbolism.

In the years following the war, de Groux's life took a more reclusive turn. He had always been a complex and somewhat volatile personality, and there are indications that he struggled with mental health issues. At one point, he was reportedly hospitalized, during which time he continued to write, producing literary works alongside his visual art.

From around 1913, even before the war fully engulfed Europe, he began to withdraw more from public life. He eventually settled in the South of France, living in Provence. This move towards a more isolated existence allowed him to focus on his art away from the pressures and politics of the Parisian art world. He continued to work, driven by his internal vision, but his public profile diminished somewhat in these later years.

His painting Les Grands Ducs (The Horned Owls), depicting three imposing owls, is an example of his later work, showcasing his continued interest in symbolic animal imagery and a powerful, somewhat unsettling atmosphere. Such works suggest a continued exploration of the mysterious and the primal, even in his relative seclusion.

Henry de Groux died in Marseille on January 12, 1930, at the age of 63. He left behind a substantial and challenging body of work that, while perhaps not always conforming to prevailing tastes, consistently demonstrated a powerful artistic will and a profound engagement with the great themes of human existence.

Legacy and Reassessment

Henry de Groux occupies a significant, if sometimes overlooked, position in the history of late 19th and early 20th-century art. As a key figure in Belgian Symbolism, he contributed to a rich artistic current that also included artists like Fernand Khnopff, Jean Delville, and his early associate Xavier Mellery. His work stands apart for its dramatic intensity, its often monumental scale, and its unflinching engagement with themes of suffering, conflict, and the human psyche.

His difficult personality and his sometimes-acrimonious relationships within the art world may have contributed to a certain marginalization during his lifetime and in subsequent art historical narratives, which often favored Parisian-centric modernism. However, the raw power of his major works, particularly Christ aux Outrages, ensures his enduring importance.

In recent decades, there has been a growing reassessment of Symbolist art in general, and figures like de Groux are being re-examined for their unique contributions. His ability to synthesize historical and mythological themes with a deeply personal and often unsettling vision speaks to the anxieties and aspirations of his era. His war art, too, provides a compelling and visceral record of a pivotal moment in modern history.

While the provided information incorrectly linked him to teaching American Ashcan School painters like William Glackens, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and John Sloan (a role correctly attributed to Robert Henri), de Groux's true legacy lies in his powerful, often disturbing, and deeply felt contributions to European Symbolism. He was an artist who dared to tackle the grand themes, to confront the darker aspects of human nature, and to forge a visual language capable of expressing the profound spiritual and psychological turmoil of his time. His work remains a testament to the enduring power of an art that seeks not merely to represent the world, but to interpret its deepest meanings.