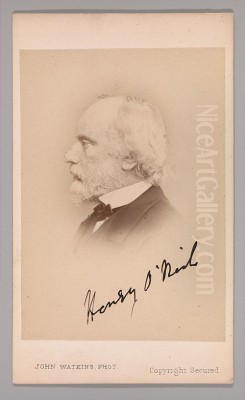

Henry Nelson O'Neil stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century British art. A painter of historical and literary subjects, a novelist, and an adventurer, O'Neil's career reflects the dynamism and contradictions of the Victorian era. Born in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 1817, he moved to England at a young age, eventually becoming an Associate of the Royal Academy and a key member of the artistic group known as "The Clique." His life, spanning from 1817 to his death in London in 1880, was marked by a dedication to narrative art, a strong opposition to the burgeoning Pre-Raphaelite movement, and a keen interest in contemporary events.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Though born in the imperial capital of Russia, Henry Nelson O'Neil's artistic identity was forged in England. His family relocated when he was a child, and by 1836, he had enrolled as a student at the prestigious Royal Academy Schools in London. This institution was the crucible for many of Britain's finest artists, and it was here that O'Neil would have received a traditional academic training, focusing on drawing from the antique, life drawing, and the study of Old Masters. His contemporaries at the Academy included figures who would become both his allies and, in some cases, the targets of his artistic criticism.

During these formative years, O'Neil developed a preference for historical and literary subjects, a genre that held considerable sway in the Victorian art world. These themes allowed artists to engage with grand narratives, moral lessons, and moments of high drama, appealing to a public increasingly interested in history, literature, and the visual arts. His early works began to appear in exhibitions, gradually building his reputation as a painter of skill and ambition.

The Formation of "The Clique"

The late 1830s and early 1840s were a period of artistic ferment in Britain. It was during this time, specifically around 1837, that O'Neil, alongside a group of fellow students and young artists, formed an informal sketching club that would come to be known as "The Clique." This group was a significant force in the London art scene, representing a youthful challenge to some of the established norms, though they were, in many ways, products of the academic system themselves.

The core members of The Clique, besides O'Neil, included Richard Dadd, who was arguably its most brilliant and tragically fated talent; William Powell Frith, who would go on to achieve immense popular success with his panoramic scenes of modern life like Derby Day and The Railway Station; Augustus Egg, known for his moralizing triptych Past and Present; Alfred Elmore, who also specialized in historical and literary scenes; John Phillip, who later gained fame as "Phillip of Spain" for his vibrant depictions of Spanish life; and Edward Matthew Ward, another prominent historical painter, known for his scenes from British and French history. Other artists like Henry Jutsum and William Bell Scott were also associated with the group at various times.

The Clique met regularly to discuss art, critique each other's work, and sketch subjects chosen by the members. Their ethos was characterized by a rejection of what they perceived as the overly idealized and sentimental tendencies in some academic art, and a desire to imbue their subjects with greater realism and emotional impact. They were, in a sense, proto-realists, though their subjects often remained rooted in history and literature rather than the gritty contemporary scenes that would later define social realism.

O'Neil's Artistic Philosophy and Opposition to Pre-Raphaelitism

Henry Nelson O'Neil was a vocal and articulate member of The Clique, and his artistic philosophy was deeply intertwined with the group's collective identity. They saw themselves as upholding certain standards of painterly skill and narrative clarity. This stance put them in direct opposition to the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), which emerged in 1848. The PRB, founded by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, advocated a return to the art of the early Italian Renaissance (before Raphael), emphasizing bright colors, meticulous detail, and often complex symbolism.

O'Neil, like his fellow Clique members, found the Pre-Raphaelites' style to be archaic, overly detailed to the point of appearing flat, and sometimes bizarre in its subject matter and execution. He was particularly outspoken in his criticism, not only in conversation but also in his writings. He penned pamphlets and articles that attacked the PRB's principles and practices, viewing their work as a regression rather than a progression in art. This public antagonism was a defining feature of the London art world in the mid-19th century, with artists and critics aligning themselves with one camp or the other. While artists like John Ruskin championed the Pre-Raphaelites, O'Neil and The Clique represented a significant body of established and emerging talent that resisted their influence.

It is important to note that The Clique itself began to dissolve by the mid-1840s, partly due to Richard Dadd's descent into madness and subsequent confinement after murdering his father in 1843. However, the bonds formed and the artistic principles espoused during its existence continued to influence its members, including O'Neil, throughout their careers.

Major Works and Thematic Concerns

O'Neil's reputation rests primarily on a series of historical and contemporary narrative paintings that captured the public imagination. His most famous works are undoubtedly Eastward, Ho!, August 1857 (exhibited Royal Academy 1858) and its sequel, Home Again, 1858 (exhibited RA 1859). These paintings depicted the departure and return of British troops during the Indian Mutiny (also known as the Sepoy Rebellion or the First War of Indian Independence).

Eastward, Ho! shows soldiers on the deck of a transport ship, bidding farewell to loved ones as they set off for India. The scene is filled with poignant vignettes: a young wife clings to her husband, an older mother blesses her son, children look on with a mixture of confusion and excitement. O'Neil masterfully captures the emotional turmoil of departure, the patriotism, and the underlying anxiety. The painting was a huge success, tapping into the intense public interest and concern surrounding the events in India. Its popularity led to the production of numerous engravings, making the image widely accessible.

Home Again portrays the return of the troops, focusing on the joyous reunions and the somber recognition of those who did not make it back. Again, O'Neil populates the canvas with individual stories, creating a powerful narrative of relief, grief, and national pride. These two works cemented O'Neil's fame as a painter who could address contemporary events with sensitivity and dramatic flair. They are prime examples of Victorian narrative painting, where the story is paramount and the artist's role is to convey it clearly and emotionally.

Beyond these iconic pieces, O'Neil explored other historical and literary themes. He was known for his depictions of the "last moments" of famous individuals, a subgenre popular in the Romantic and Victorian periods. The Last Moments of Mozart (1849) and The Last Moments of Raphael (1866) are notable examples. These works are characterized by a romanticized and often sentimental portrayal of genius facing death, surrounded by grieving admirers or symbols of their achievements. In The Last Moments of Mozart, for instance, the dying composer is often shown attempting to conduct a final passage of his Requiem, a scene that, while historically dubious, resonated with the era's fascination with artistic martyrdom.

Another significant work, The Sleeping Soldier, also known as A Volunteer, touches upon themes of domesticity and duty, showing a soldier asleep in a domestic setting, perhaps on leave or before deployment, highlighting the contrast between the peace of home and the demands of military life. His paintings often featured vivid, though not Pre-Raphaelite bright, colors and a strong sense of theatrical composition, guiding the viewer's eye through the narrative. He exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy, becoming an Associate (ARA) in 1860, a testament to his standing in the art world.

The Atlantic Telegraph Expeditions: Art and Adventure

A particularly unusual and fascinating chapter in O'Neil's life involved his participation in the attempts to lay the transatlantic telegraph cable. In July 1865, he was aboard the SS Great Eastern, the colossal steamship chartered for the task of laying the cable between Valentia Island, Ireland, and Heart's Content, Newfoundland. O'Neil was there with the intention of documenting this monumental feat of engineering through his art.

Unfortunately, this first attempt in 1865 was unsuccessful; the cable snapped and was lost in deep water. Despite the mission's failure, O'Neil's experience was not entirely fruitless. He edited and provided illustrations for The Atlantic Telegraph, a shipboard newsletter produced during the voyage. Upon his return, he published an account of the expedition, offering a first-hand perspective on the challenges and drama of the undertaking.

Undeterred, O'Neil joined the Great Eastern again for the successful 1866 expedition, which not only laid a new cable but also managed to retrieve and complete the one lost the previous year. From this second voyage, he produced several paintings and prints related to the cable-laying process. He also contributed a humorous account of his experiences to London Society magazine. These episodes demonstrate O'Neil's adventurous spirit and his engagement with the technological marvels of his age, extending his artistic interests beyond purely historical or literary subjects. His involvement provides a unique intersection of art, science, and Victorian enterprise.

Literary Pursuits and Later Career

In addition to his painting and occasional journalism, Henry Nelson O'Neil was also a novelist. He authored several works of fiction, though these are less well-remembered today than his paintings. His literary endeavors, however, underscore his narrative inclinations and his desire to tell stories, whether on canvas or in print. Titles such as Satirical Dialogues (1870) and The Age of Stucco: a satire in three cantos (1871) suggest a critical and perhaps humorous engagement with contemporary society, echoing some of the satirical intent that occasionally surfaced in the discussions of The Clique.

Throughout the 1860s and 1870s, O'Neil continued to paint and exhibit, though perhaps without achieving the same level of public acclaim as he had with Eastward, Ho! and Home Again. The art world was changing, with new movements and styles gaining prominence. The influence of French Impressionism was beginning to be felt in Britain, and aestheticism was on the rise, shifting focus away from narrative content towards formal qualities and "art for art's sake."

Despite these shifts, O'Neil remained committed to his narrative style. He continued to produce historical scenes, genre paintings, and portraits. His body of work reflects a consistent dedication to the principles he had developed early in his career, emphasizing clear storytelling, emotional engagement, and competent, if not always groundbreaking, painterly technique.

Contemporaries and Artistic Context

To fully appreciate O'Neil's position, it's useful to consider him within the broader context of Victorian art. He was a contemporary of many notable figures. Beyond The Clique members (Dadd, Frith, Egg, Elmore, Phillip, Ward), and the Pre-Raphaelites (Millais, Hunt, Rossetti, and their associate Ford Madox Brown), there were other significant historical painters like Daniel Maclise, known for his grand frescoes in the Houses of Parliament, and Charles Landseer (brother of the more famous Edwin Landseer), who also taught some of The Clique members.

The Victorian era saw a flourishing of genre painting, with artists like Thomas Webster depicting charming scenes of rural life, and Luke Fildes later tackling more challenging social realist themes. Portraiture was also in high demand, with artists like Sir Francis Grant and George Frederic Watts achieving great success. O'Neil's work, with its blend of historical narrative, contemporary relevance (as in the Indian Mutiny paintings), and romantic sentiment, fits comfortably within this diverse but predominantly narrative-driven artistic landscape.

His opposition to the Pre-Raphaelites places him in a specific camp within the complex artistic debates of the time. While the PRB's influence would prove to be long-lasting, particularly on the Aesthetic Movement and later Symbolism, artists like O'Neil represented a more traditional, yet still popular, approach to painting that valued academic skill and accessible storytelling.

Legacy and Reassessment

Henry Nelson O'Neil died in Kensington, London, on March 13, 1880. In the decades following his death, his reputation, like that of many Victorian narrative painters, declined as modernist aesthetics came to dominate art criticism. The emphasis on storytelling and sentiment that had made his work so popular in his lifetime was often dismissed by early 20th-century critics who favored formal innovation and abstraction.

However, from the mid-20th century onwards, there has been a significant reassessment of Victorian art. Scholars and curators have begun to appreciate the richness, complexity, and technical skill of painters like O'Neil. His works, particularly Eastward, Ho! and Home Again, are now recognized as important documents of their time, reflecting Victorian attitudes towards empire, war, family, and national identity. They are also valued for their artistic merits, their skillful composition, and their ability to convey powerful emotions.

While he may not be as widely known today as some of his contemporaries like William Powell Frith or the leading Pre-Raphaelites, Henry Nelson O'Neil remains a key figure for understanding the dynamics of the Victorian art world. He was a successful painter within the Royal Academy system, a central member of an influential artistic group, a vocal participant in the aesthetic debates of his day, and an artist whose work captured significant moments in 19th-century British history and culture. His life and art offer a compelling window into the ambitions, anxieties, and artistic currents of a transformative era. His participation in the Atlantic cable expeditions also adds a unique dimension to his biography, marking him as an artist who was not afraid to engage directly with the technological frontiers of his time.