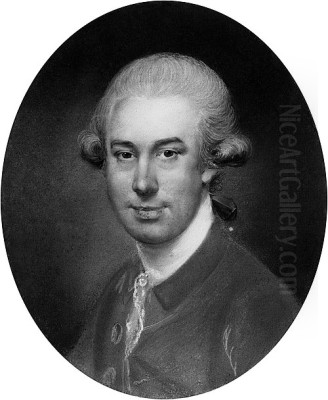

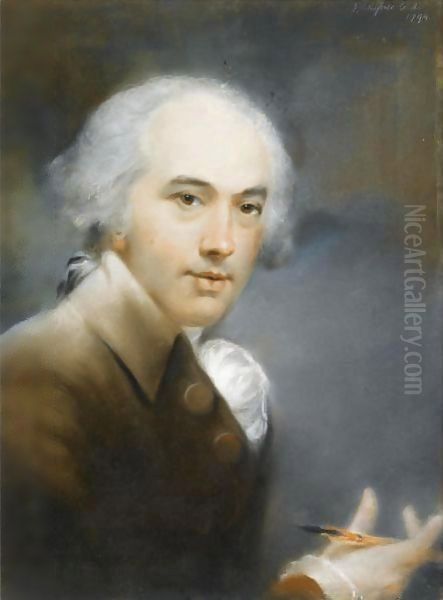

John Russell stands as one of the most significant figures in British art during the latter half of the 18th century. Born in 1745 and passing away in 1806, his career coincided with a vibrant period in British portraiture, dominated by giants like Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough. Yet, Russell carved a distinct and highly respected niche for himself, primarily as a master of the pastel medium. His technical brilliance, combined with a keen ability to capture the likeness and character of his sitters, earned him widespread acclaim, royal patronage, and a lasting legacy that extended beyond the art world into the realm of scientific observation. This exploration delves into the life, work, artistic style, and unique intellectual pursuits of this multifaceted artist.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

John Russell was born in Guildford, Surrey, in 1745. His family background provided a solid foundation; his father, also named John Russell, was a respected figure in the town – a bookseller and printer who served as mayor of Guildford on four separate occasions. This connection to local prominence likely offered the young Russell a degree of social stability and perhaps exposure to the educated circles of the town. From an early age, Russell demonstrated a clear aptitude for art, a talent that his family seemingly encouraged.

Recognizing his potential, Russell was sent to London to receive formal artistic training. He became a pupil of Francis Cotes RA (c. 1726–1770), who was himself a preeminent portrait painter, particularly renowned for his work in pastels. Cotes was a founding member of the Royal Academy and a significant force in popularizing the pastel medium in Britain, adapting the continental fashion for this delicate art form to British tastes. Studying under Cotes provided Russell with invaluable technical grounding in both oil and pastel, but it was in the latter that he would truly excel and eventually surpass his master.

The apprenticeship with Cotes was crucial. It placed Russell at the heart of the London art scene and exposed him to the techniques and standards expected of a leading portraitist. Cotes's own style, often characterized by its fresh colours and competent draughtsmanship, undoubtedly influenced Russell, but the pupil soon developed his own distinctive approach. By 1767, feeling sufficiently skilled and ambitious, Russell established his own portrait practice in London, ready to make his mark.

Establishing a Reputation: The Rise of a Pastel Virtuoso

Setting up a studio in London marked the beginning of Russell's independent professional career. The late 1760s and 1770s were a period of consolidation and growing recognition. He began exhibiting his work, primarily at the Society of Artists and later, more significantly, at the newly founded Royal Academy of Arts. His skill, particularly in the challenging medium of pastel, quickly drew attention. Pastel offered a vibrancy and immediacy distinct from oil painting, allowing for rapid execution and luminous colour, qualities Russell exploited to great effect.

His technical proficiency was remarkable. Contemporaries and later critics noted his complete mastery over the medium. He developed specific techniques, often favouring blue paper prepared with a textured ground, which allowed the pastel pigments to adhere effectively and provided a cool mid-tone against which his colours could resonate. He was known for his skillful blending and 'sweetening' of tones, using his fingers, stumps (rolled paper or leather), or brushes to create soft transitions, particularly in flesh tones, while often retaining crisper, more linear details in clothing or accessories using harder pastel sticks or black chalk.

This technical command was paired with an exceptional ability to capture not just a physical likeness but also the perceived character and inner life of his sitters. His portraits are often described as lively and engaging, avoiding the stiffness that could sometimes affect formal portraiture. This quality earned him increasing commissions from a discerning clientele, ranging from the aristocracy and gentry to the professional classes and fellow members of the Methodist community, with whom he became deeply involved. His reputation grew steadily, solidifying his position as a leading portraitist.

The Art of Pastel in 18th-Century Britain

To fully appreciate Russell's achievement, it is important to understand the status of pastel painting in 18th-century Britain. While popular on the Continent, particularly in France with artists like Maurice Quentin de La Tour and Jean-Baptiste Perronneau, pastels in Britain occupied a slightly ambiguous position. They were admired for their brilliance and speed but sometimes considered less permanent or 'serious' than oil painting. Artists like Francis Cotes, the Swiss émigré Jean-Étienne Liotard (who worked in London for periods), and later Russell himself, were instrumental in elevating the medium's status.

Russell's work demonstrated that pastels could achieve a depth, richness, and psychological insight comparable to oils. His approach, while perhaps influenced by French Rococo elegance learned via Cotes, developed into a distinctly British style – often more direct, less overtly flamboyant, and perhaps imbued with a greater sense of naturalism or moral seriousness, particularly in his portraits of fellow Methodists. He navigated the perceived limitations of the medium, developing fixative techniques (though the exact methods remain debated) to improve permanence and handling large-scale compositions with confidence.

He even codified his knowledge, publishing "Elements of Painting with Crayons" in 1772 (a second edition appeared in 1776). This treatise served as a practical guide for aspiring pastel artists, detailing materials, preparation of grounds, application techniques, and colour theory. Its publication further cemented Russell's authority in the field and provided valuable insights into his working methods, contributing significantly to the technical literature of art in Britain.

Stylistic Signature and Technical Mastery

John Russell's artistic style is defined by its vibrancy, sensitivity, and technical assurance. Working primarily in pastel, he achieved effects of light, texture, and expression that were widely admired. His palette was often bright and clear, making full use of the inherent luminosity of pastel pigments. He was particularly adept at rendering the complexities of flesh tones, capturing the subtle warmth and translucency of skin, often set against the rich textures of contemporary fabrics like silk, satin, and velvet.

His use of blue paper as a support became a hallmark. This choice provided an immediate middle tone, allowing him to build up highlights effectively with lighter pastels and define shadows with darker tones or black chalk. The texture of the paper itself often played a role, interacting with the powdery pigment to create a lively surface. Russell skillfully combined broad areas of smoothly blended colour with passages of more broken, linear strokes, adding dynamism and focus. The use of black chalk or charcoal for reinforcing outlines or adding sharp details, particularly in eyes or hair, gave his portraits structure and intensity.

Compared to his master, Francis Cotes, Russell's work is often seen as possessing greater psychological depth and perhaps a more vigorous handling. While Cotes excelled in charm and elegance, Russell seemed to probe deeper into the sitter's personality. His portraits convey a sense of presence and immediacy. Critics lauded his ability to capture fleeting expressions and the 'speaking likeness' that patrons desired. This combination of technical virtuosity and perceptive characterisation led some contemporaries to rank his achievements in pastel alongside the towering figure of Sir Joshua Reynolds in oil.

Portraiture: A Gallery of Georgian Society

The core of John Russell's output was portraiture. His sitters represented a broad cross-section of Georgian society. He painted members of the Royal Family, aristocracy, landed gentry, prominent clergymen, professional men, merchants, fellow artists, and numerous women and children. His connection to the Methodist movement also led to many portraits of its leading figures and their families, works often imbued with a particular sense of piety or quiet domesticity.

Among his most celebrated works are portraits that showcase his skill with different ages and characters. His depictions of children are particularly noted for their charm and lack of sentimentality, capturing youthful energy and innocence with directness. A fine example is Charles Wesley Junior (c. 1771), portraying the young musician with sensitivity. His portraits of women, such as Mrs. G. Medley (1777) or the elegant Mary Hall (c. 1790s, now in the Louvre), demonstrate his ability to render fashionable attire and convey grace and poise.

Works like William Man Godschall (1791, Metropolitan Museum of Art) show his capacity for portraying mature male sitters with dignity and character. The double portrait Mrs. Robert Shurlock and Her Daughter, Henrietta (c. 1801, Metropolitan Museum of Art) is a later work displaying continued mastery in composition and the tender depiction of familial bonds. Although primarily a pastelist, he did occasionally work in oils, but it is his pastel oeuvre that forms the bedrock of his reputation. His consistent quality and prolific output made him one of the most sought-after portraitists of his time.

Royal Patronage and Academic Recognition

A significant marker of Russell's success was the attainment of royal patronage. In 1789, he was appointed Painter in Crayons to King George III and Queen Charlotte. Shortly thereafter, in 1790, he received the same appointment to George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), and subsequently to Frederick, Duke of York. These appointments were not merely honorific; they brought prestigious commissions and cemented his status at the pinnacle of his profession. His portrait sketch of George IV (likely from the Prince of Wales period, despite the potentially confusing date sometimes cited) reflects this connection.

Parallel to royal favour was recognition from his peers within the artistic establishment. Russell had begun exhibiting at the Royal Academy soon after its foundation. His talent was formally acknowledged in 1772 when he was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA). This was followed by his election as a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1788, a distinction held by the most respected artists in the country, including Sir Joshua Reynolds (the first President), Thomas Gainsborough, Benjamin West (who succeeded Reynolds as President), Angelica Kauffman, and his former master Francis Cotes (though Cotes died before Russell achieved full RA status).

Membership in the Royal Academy provided exhibition opportunities at the prestigious Annual Exhibition, enhanced professional standing, and placed him within the central institution shaping British art. His works were consistently well-received at the RA exhibitions, further spreading his fame both nationally and, to some extent, internationally. His reputation reached France, where pastel painting had a long and distinguished tradition, and his work was appreciated for its technical brilliance, even if viewed through the lens of differing national tastes.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

John Russell operated within a rich and competitive artistic landscape. His primary point of comparison was often Sir Joshua Reynolds, the dominant force in British portraiture and President of the Royal Academy for much of Russell's career. While Reynolds worked predominantly in oil and aimed for a 'Grand Manner' often incorporating historical or allegorical references, Russell's strength lay in the more intimate and immediate medium of pastel, focusing on direct characterisation. Thomas Gainsborough, another giant, was perhaps closer in sensibility, also excelling in capturing likeness with a fluid touch and occasionally working in pastel himself.

Russell's direct competitors in the pastel market included artists like Daniel Gardner, known for his small-scale, elegant portraits often combining gouache and pastel, and the Irish artist Hugh Douglas Hamilton, who also enjoyed considerable success with pastel portraits in London and Italy. Russell's relationship with his teacher, Francis Cotes, was foundational, though Russell ultimately developed a more robust and arguably more penetrating style.

Beyond portraitists, Russell interacted with figures across London's cultural spectrum. His religious connections brought him into contact with John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, whom he knew and whose circle he painted. His scientific interests likely connected him with members of the Royal Society or other scientifically-minded individuals, perhaps including Sir Joseph Banks, the influential naturalist and President of the Royal Society. He was acquainted with fellow artists like George Duley Gregory, whom he painted and may have known as a neighbour on Newman Street, a popular area for artists. He also reportedly showed his lunar drawings to the history painter William Hamilton RA, receiving encouragement. Other prominent RAs during his time included the Swiss-born Angelica Kauffman and the American-born Benjamin West. Miniaturists like Ozias Humphry also worked in related fields.

Faith and Life: The Fervent Methodist

A defining aspect of John Russell's life, and one that significantly impacted his personal relationships and perhaps subtly influenced his art, was his deep religious faith. Around 1764, as a young man, he underwent a profound religious conversion experience and became a devout follower of Methodism, a movement characterized by its emphasis on personal faith, evangelical zeal, and disciplined living. This conversion was not a passive affiliation; it became central to his identity.

Russell became known for his piety, which bordered on the zealous. He kept detailed diaries, large portions of which survive, recording his spiritual struggles, prayers, religious observances, and his attempts to live according to strict Methodist principles. These diaries offer a fascinating, if sometimes intense, glimpse into the inner life of an 18th-century evangelical Christian. His faith provided him with a strong moral compass but also led to personal conflicts.

He felt a strong imperative to share his faith and reportedly made strenuous efforts to convert friends, family members, and even patrons to Methodism. This proselytizing zeal was not always well-received. An early encounter involved the notorious Dr. William Dodd (whom Russell painted), who apparently tried to steer Russell towards ministry, though Russell remained committed to art. Later, Russell's own efforts to convert others, including attempts directed towards figures like Selina, Countess of Huntingdon (a major patron of Methodism, suggesting a complex interaction), sometimes caused friction and strained relationships. His diary entries document the personal cost of these encounters and his unwavering commitment despite the difficulties. This intensity of belief adds another layer to the understanding of Russell as a man of strong convictions, operating in both the fashionable art world and the fervent religious subculture of Methodism.

Beyond Portraiture: Astronomy and 'Selenographia'

Remarkably, John Russell's talents and passions extended beyond the canvas and pastel paper into the realm of science, specifically astronomy. He developed a deep fascination with the Moon, dedicating countless hours over many years to meticulous observation using telescopes. This was not merely a casual hobby; it was a serious scientific pursuit undertaken with artistic precision. He aimed to create the most accurate and detailed representation of the lunar surface available at the time.

Starting in the mid-1760s and continuing for decades, Russell made numerous drawings of the Moon in various phases. He invented a specialized apparatus, which he called a "Selenographia," to help him accurately map the lunar features he observed. His artistic skills were invaluable in this endeavour, allowing him to render the subtle play of light and shadow across the craters, mountains, and maria (the dark lunar plains) with exceptional fidelity. He sought to capture the Moon's appearance more accurately than previous maps had allowed.

The culmination of this long effort was the publication in 1797 of a large, engraved lunar map and accompanying materials, also titled Selenographia, or the lunar map. He produced two large engraved plates showing the full Moon, along with detailed representations of specific lunar regions. These were highly detailed and represented a significant contribution to lunar cartography in the era before photography. He presented his work to figures like John Wesley and William Hamilton RA, and likely sought validation from scientific figures of the day, perhaps comparing his work to that of contemporary astronomers like Sir William Herschel, the discoverer of Uranus. This intersection of art and science highlights Russell's inquisitive mind and his dedication to empirical observation, reflecting the broader spirit of the Enlightenment.

Later Life, Legacy, and Enduring Reputation

John Russell remained active as an artist into the early 19th century. While pastel portraiture remained his mainstay, some sources suggest he explored other genres, possibly including landscape or subject pictures, and continued to work occasionally in oil, though these form a minor part of his known output. He continued to exhibit at the Royal Academy and maintained his royal appointments. His reputation as the foremost pastel painter in Britain was secure.

Russell never married and dedicated much of his life to his art and his religious devotions. His detailed diaries continued to chronicle his experiences and beliefs. In 1806, while working in Hull in the north of England, he contracted typhus fever and died at the age of 61. His estate, including a significant collection of his own works and his diaries, passed to his descendants. He was buried in Hull.

John Russell's legacy is multifaceted. He is remembered primarily as a master of pastel, an artist who brought the medium to a peak of technical brilliance and expressive power in Britain. His portraits provide a valuable visual record of Georgian society, capturing individuals from royalty to the middle classes with skill and sensitivity. His treatise, Elements of Painting with Crayons, remains an important document for understanding 18th-century pastel techniques.

Furthermore, his dedicated work in lunar observation and the creation of Selenographia mark him as a unique figure who bridged the worlds of art and science. While later astronomical observations surpassed his maps, they were a significant achievement for their time. His deep religious faith adds another dimension, revealing the complex interplay of art, science, and personal conviction in his life. Although perhaps overshadowed in general art history by Reynolds and Gainsborough, Russell's work has consistently been held in high regard by specialists. Interest in his work saw a resurgence, particularly among French collectors, in the early 20th century, and his paintings are held in major museums worldwide, ensuring his place as a key figure in the history of British art.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

John Russell RA was more than just a highly skilled portrait painter. He was a technical innovator in the pastel medium, a perceptive chronicler of his time, a man of profound and sometimes challenging religious conviction, and a dedicated amateur scientist who mapped the Moon with artistic precision. His ability to capture the essence of his sitters, combined with the luminous beauty of his chosen medium, resulted in portraits that remain fresh and engaging centuries later. His royal patronage and election to the Royal Academy attest to the high esteem in which he was held during his lifetime. While navigating the complex social, artistic, and religious currents of Georgian Britain, Russell forged a unique path, leaving behind a body of work and a life story that continue to fascinate. He stands as a testament to the rich diversity of talent within 18th-century British art, a master whose delicate pastels captured both human likeness and celestial landscapes with singular vision.