Michael Sweerts (1618-1664) stands as one of the more enigmatic and intriguing figures of 17th-century Flemish painting. Born in Brussels, his life was a tapestry woven with threads of artistic brilliance, pedagogical ambition, profound religious conviction, and extensive travel, culminating in a mysterious death in faraway India. Though his output was relatively small and his fame somewhat obscured for centuries, modern scholarship has increasingly recognized his unique contribution to Baroque art, characterized by a sensitive realism, classical restraint, and a deeply humanistic portrayal of his subjects.

Early Life and Artistic Genesis

Born in Brussels and baptized on September 29, 1618, Michael Sweerts' early life and artistic training remain largely undocumented, a commonality for many artists of the period before they established significant reputations. Brussels, at the time, was a vibrant artistic center within the Spanish Netherlands, still basking in the afterglow of Peter Paul Rubens' monumental influence and benefiting from the legacy of artists like Anthony van Dyck and Jacob Jordaens. While no specific teacher is definitively known for Sweerts, he would have been immersed in a rich artistic environment that valued technical skill, dynamic composition, and a robust engagement with both religious and secular themes. It is presumed he received foundational training in Brussels before embarking on the almost obligatory journey for ambitious Northern European artists: to Italy.

The Roman Sojourn: A Crucible of Styles

Sweerts is documented in Rome by 1646, a city that was then the undisputed capital of the European art world. It was a melting pot of artists from across the continent, all drawn by the legacy of antiquity, the High Renaissance masters like Raphael and Michelangelo, and the more recent, revolutionary impact of Caravaggio. In Rome, Sweerts became associated, albeit informally as an "aggregato," with the prestigious Accademia di San Luca, an association of artists dedicated to elevating the status of their profession. This connection suggests an artist keen on engaging with the theoretical and academic aspects of art, not merely its practice.

During his Roman years, which lasted until around 1656 (with a brief return to Brussels in between), Sweerts absorbed a multitude of influences. He was undoubtedly aware of the works of the "Bamboccianti," a group of mostly Dutch and Flemish genre painters active in Rome, led by Pieter van Laer, nicknamed "Il Bamboccio" (meaning "ugly doll" or "puppet"). These artists specialized in scenes of everyday Roman life, depicting peasants, street vendors, and the bustling activity of the city's piazzas and taverns. Sweerts certainly painted genre scenes, such as men playing cards or dice, or scenes of street life, but his approach often differed from the sometimes crude or overly picturesque style of some Bamboccianti. His figures, even in humble settings, possess a dignity and psychological depth that sets them apart.

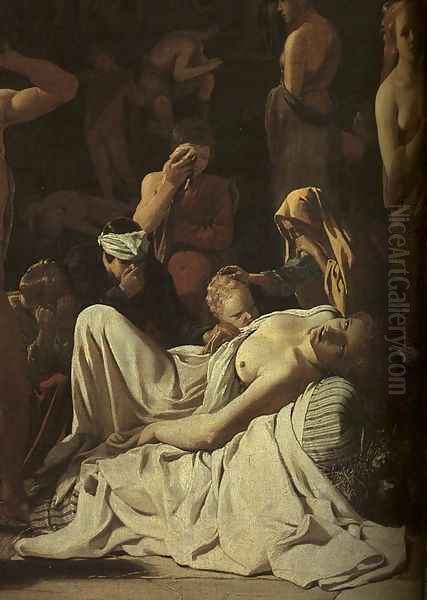

A significant influence during this period was the French classical painter Nicolas Poussin, who was also active in Rome. Poussin's emphasis on order, clarity, historical and mythological subjects, and a carefully structured compositional approach can be discerned in some of Sweerts' more ambitious works. One such painting, often cited in this context, is his Plague in an Ancient City (c. 1650-1652). This dramatic composition, with its frieze-like arrangement of figures and its depiction of suffering and stoicism, clearly echoes Poussin's grand historical narratives and demonstrates Sweerts' capacity to engage with complex, multi-figure compositions and profound human themes. Other artists whose work Sweerts would have encountered and likely studied in Rome include the French landscape painter Claude Lorrain, known for his idealized classical landscapes, and Italian masters like Guido Reni or Domenichino, who continued the classical tradition. The pervasive influence of Caravaggio, with his dramatic use of chiaroscuro and unidealized realism, also left an indelible mark on Roman art, and its echoes can be felt in Sweerts' own sensitive handling of light and shadow.

Distinctive Artistic Style and Thematic Concerns

Michael Sweerts' artistic style is notable for its subtle fusion of Northern European realism with an Italianate classicism. His paintings are often characterized by a distinctive cool, silvery tonality, which lends them an air of quiet introspection and distinguishes them from the warmer palettes of many of his Italian contemporaries or even some of his fellow Northerners working in Italy. His color harmonies are balanced and sophisticated, contributing to a lyrical, almost melancholic mood in many of his works.

He excelled in various genres. His genre scenes, as mentioned, often depict common people but with an unusual empathy and lack of caricature. Works like Man Holding a Jug (also known as The Drinker) showcase his ability to capture individual character and a sense of quiet presence. The figure is rendered with a palpable sense of volume and a careful attention to the play of light on surfaces, from the rough fabric of the man's clothing to the gleam of the earthenware jug.

Sweerts was also a gifted portraitist. His portraits and "tronies" (character studies not intended as formal portraits of specific individuals) are among his most compelling works. Woman's Head (or Head of a Woman) is a prime example, showcasing his delicate modeling of features and his ability to convey a sense of inner life. These works often possess a psychological acuity reminiscent of Dutch masters like Rembrandt van Rijn or Johannes Vermeer, though Sweerts' approach is distinctly his own. The comparison to Vermeer, particularly in the quiet dignity and luminous quality of some of his figures, has been noted by scholars, although direct influence is debatable and more likely a shared sensibility of the era.

His series of paintings depicting The Seven Acts of Mercy or individual works like An Artist Painting a Peasant (or The Artist's Studio) reveal his interest in both social commentary and the nature of artistic practice itself. The studio scenes, in particular, offer a glimpse into the world of the artist and the process of creation, a theme popular in the Netherlands with artists like Adriaen van Ostade or Gerrit Dou. Sweerts' depictions often emphasize the diligence and skill involved in art, aligning with his academic interests.

Printmaking and Pedagogical Ambitions in Brussels

Around 1655-1656, Sweerts was back in Brussels. During this period, he produced a significant series of etchings, Diversae Facies in usum iuvenum et aliorum ("Various Faces for the Use of Youth and Others"), published in 1656. This collection of character heads and studies served as a drawing manual, reflecting his interest in art education. It is documented that he planned to open a drawing academy in Brussels, intending to teach according to the principles he had absorbed, likely including those of the Italian academies. He even became a member of the Brussels Guild of Saint Luke in 1659. However, this pedagogical project ultimately did not come to full fruition, perhaps due to the next, unexpected turn in his life. His dedication to teaching, however, aligns him with other artists who produced didactic materials, such as Odoardo Fialetti in Italy.

The Missionary Call and Final Years

In a surprising and life-altering decision, Michael Sweerts became deeply involved with the Lazarists (Congregation of the Mission), a Catholic religious order founded by Saint Vincent de Paul, which was involved in missionary work. Around 1660-1661, he joined a group of missionaries led by François Pallu, a bishop of the newly formed Paris Foreign Missions Society, who were destined for the Far East. Sweerts, as a lay brother, intended to use his artistic skills in the service of the mission.

The journey was arduous. The group traveled overland from Paris, through Syria and Persia. Accounts from Pallu suggest that Sweerts' temperament proved difficult for communal missionary life; he was described as somewhat unstable and prone to disputes. Consequently, he was dismissed from the mission in Isfahan, Persia, around 1662. Undeterred, Sweerts continued his journey independently, eventually reaching the Portuguese colony of Goa in India. It was here, in Goa, that Michael Sweerts died, around 1664, his final years shrouded in the same mystery that characterized much of his life. This dramatic shift from a promising artistic and teaching career to a fervent, if troubled, missionary path is one of the most fascinating aspects of his biography.

Notable Works: A Closer Look

Sweerts' oeuvre, though not vast (around 40 paintings are generally attributed to him today, along with his etchings), contains several masterpieces that highlight his unique talents.

Plague in an Ancient City (c. 1650-1652): This large-scale work, likely painted in Rome, demonstrates his ambition to tackle grand historical themes in the classical tradition of Poussin. The carefully arranged figures, the dramatic expressions of grief and despair, and the architectural setting all contribute to its powerful impact. It showcases his ability to manage complex compositions and convey profound human emotion.

The Five Senses (c. 1650s): This series, of which several paintings like Smell, Touch, and Taste survive, depicts allegorical figures or genre scenes representing each sense. These works combine his skill in rendering textures and human expression with a thoughtful engagement with traditional allegorical themes, a popular subject for artists like Jan Brueghel the Elder or later, Jacques Linard.

An Artist's Studio (or variations like A Painter's Studio, Drawing School) (c. 1648-1650): Several paintings explore this theme. They often depict young artists diligently drawing from plaster casts of classical sculptures or from life models, reflecting Sweerts' own academic interests and his belief in rigorous training. These scenes provide valuable insight into 17th-century artistic practices.

Boy with a Turban and a Nosegay (or similar "tronie" portraits): Works like this, or the aforementioned Woman's Head and Boy with a Hat, are celebrated for their psychological penetration and exquisite handling of paint. The subjects are often anonymous, allowing Sweerts to focus on expression, character, and the play of light. They possess a timeless quality and a quiet intensity.

Man Holding a Jug (c. 1650s): A fine example of his dignified genre painting, this work captures a moment of everyday life with sobriety and realism. The figure's introspective gaze and the solid, sculptural quality of his form are characteristic of Sweerts' best work in this vein.

Interactions with Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Sweerts' time in Rome placed him at the heart of a vibrant artistic community. Beyond Poussin and the Bamboccianti, he would have known or been aware of numerous other artists. His connection with the Accademia di San Luca suggests interactions with Italian artists like Alessandro Algardi or perhaps younger painters influenced by the classical revival. The Dutch and Flemish community in Rome was tight-knit, often gathering in groups like the "Bentvueghels" (Birds of a Feather). While Sweerts' direct involvement with this often boisterous group is not clearly documented, he certainly moved in similar circles. Artists like Johannes Lingelbach, another Northern painter of Italianate scenes, were his contemporaries in Rome.

His style also shows an awareness of developments in the Netherlands. The intimate genre scenes of artists like Gerard ter Borch or Pieter de Hooch, with their refined execution and quiet domesticity, share some common ground with Sweerts' more polished genre pieces, though Sweerts' figures often have a more sculptural, classical feel. His portraiture, while distinct, can be seen within the broader context of 17th-century character studies, a field in which Rembrandt excelled, but also pursued by artists like Frans Hals, albeit with a more extroverted flair. The influence of earlier Flemish masters like Anthony van Dyck, particularly in the elegance of some of his portraits, cannot be discounted from his formative years. He also reportedly had pupils in Brussels, such as Willem Drost, who himself had been a pupil of Rembrandt and also spent time in Italy.

Anecdotes, Mysteries, and Lasting Questions

Michael Sweerts' life is punctuated by intriguing questions and a certain air of mystery. His relatively sudden and fervent embrace of missionary work, leading him to abandon his established artistic career, remains a subject of speculation. Was it a profound spiritual crisis, a disillusionment with the art world, or a combination of factors? The accounts of his difficult personality during the mission add another layer to his complex character.

The scarcity of his works, coupled with their high quality, has made each rediscovered or reattributed painting a significant event in the art historical world. The debate about his potential influence on or connection to Vermeer, while largely speculative, highlights the evocative power and refined sensibility present in his best paintings. His "tronies," like Boy with a Hat, continue to fascinate viewers with their enigmatic expressions and the unknown identities of their subjects, inviting contemplation on the nature of portraiture and individual identity. His death in Goa, far from the European art centers, provides a poignant and somewhat romantic end to a life less ordinary.

Legacy and Rediscovery

For centuries after his death, Michael Sweerts was a relatively obscure figure, his name known primarily to connoisseurs and specialized scholars. His decision to leave Europe for missionary work undoubtedly contributed to this period of neglect, as he was no longer present to build his reputation or influence a new generation of artists directly in the main artistic centers.

However, the 20th century, particularly its latter half, witnessed a significant scholarly reassessment and rediscovery of his work. Exhibitions and publications brought his paintings to a wider audience, and art historians began to appreciate the unique qualities of his art: the blend of Northern realism and Italian classicism, the psychological depth of his portraits, the dignified humanity of his genre figures, and the cool, luminous quality of his palette.

Today, Michael Sweerts is recognized as an important and highly individualistic painter of the Baroque period. He is seen as a key figure among the Netherlandish artists working in Rome, contributing to the rich cross-cultural exchanges that characterized the era. His work is admired for its technical finesse, its emotional resonance, and its quiet, contemplative beauty. While he may not have achieved the widespread fame of contemporaries like Rembrandt or Rubens during his lifetime or in the centuries immediately following, his artistic legacy is now secure, his paintings cherished in major museums around the world as testaments to a singular talent.

Conclusion: An Artist of Quiet Distinction

Michael Sweerts remains a figure of fascination, an artist whose life journey was as unconventional as his art was refined. From the bustling streets of Rome to the aspiring academies of Brussels, and finally to the distant shores of India, his path was marked by a restless spirit and a profound engagement with both the human condition and the divine. His paintings, with their subtle emotional depth, their masterful handling of light and form, and their unique blend of realism and classicism, continue to speak to contemporary audiences. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of art that, while perhaps quiet and introspective, possesses a profound and lasting resonance, securing his place as a distinct and valuable voice in the rich chorus of 17th-century European art.