Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni, known universally as Michelangelo, stands as one of the most formidable and influential figures in the history of Western art. Born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Tuscany, and passing away in Rome on February 18, 1564, at the venerable age of 88, his life spanned a period of immense artistic and cultural flourishing. A sculptor, painter, architect, and poet, Michelangelo embodied the Renaissance ideal of the "Uomo Universale" or Universal Man. His unparalleled genius, fierce independence, and profound spirituality left an indelible mark on art, shaping its course for centuries to come. His works, characterized by their emotional intensity, anatomical precision, and monumental scale, continue to inspire awe and command reverence worldwide.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Michelangelo's early life was marked by a distinct inclination towards the arts, a path not initially favored by his family. His father, Lodovico di Leonardo Buonarroti Simoni, was a government official, and the family, while of noble lineage, was not wealthy. His mother, Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena, passed away when Michelangelo was merely six years old. Subsequently, he was sent to live with a stonecutter and his wife in the town of Settignano, where his father owned a marble quarry. Michelangelo would later jest that he imbibed the love of chisel and mallet with his wet nurse's milk, a humorous nod to this early exposure to the world of stone.

Despite his father's initial opposition, who perhaps envisioned a more conventional career for his son, Michelangelo's determination to pursue art was unyielding. Around the age of 13, in 1488, he was apprenticed to Domenico Ghirlandaio, one of Florence's most prominent painters. Ghirlandaio's workshop was a bustling center of artistic production, and here Michelangelo would have learned the fundamentals of fresco painting and draftsmanship. However, his temperament, already showing signs of a restless and independent spirit, reportedly led to friction. Sources like Giorgio Vasari, his contemporary and biographer, note that Michelangelo quickly surpassed his master, demonstrating an uncanny ability to capture form and movement. He also studied the works of earlier Florentine masters like Giotto and Masaccio, whose frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel he meticulously copied, absorbing their lessons in human emotion and three-dimensional representation.

The Patronage of the Medici and Early Sculptures

A pivotal moment in Michelangelo's youth came through his association with the powerful Medici family, Florence's de facto rulers and lavish patrons of the arts. Lorenzo de' Medici, known as "il Magnifico," recognized the young artist's prodigious talent. Around 1490, Michelangelo was invited to join Lorenzo's informal academy, a humanist circle that gathered in the Medici Palace and its sculpture garden near San Marco. Here, he was exposed to Lorenzo's vast collection of ancient Roman sculpture and came under the tutelage of Bertoldo di Giovanni, a former pupil of Donatello.

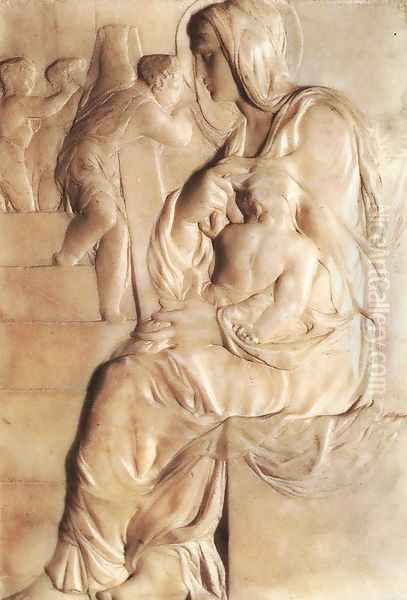

Living in the Medici household for a few years, Michelangelo dined with the family and absorbed the Neoplatonic philosophy prevalent in Lorenzo's circle, which profoundly influenced his artistic vision, particularly his conception of ideal beauty and the human form as a vessel for the divine. During this period, he created his earliest known sculptures: the Madonna of the Stairs (c. 1491), a delicate low-relief showing the influence of Donatello, and the Battle of the Centaurs (c. 1492), a dynamic and complex high-relief inspired by classical sarcophagi, already showcasing his mastery of anatomy and dramatic composition. Lorenzo's death in 1492 marked the end of this formative period, and political instability soon followed in Florence.

First Sojourn in Rome and Emergent Fame

After Lorenzo's death and the subsequent expulsion of the Medici from Florence in 1494, Michelangelo traveled, spending time in Venice and Bologna. In Bologna, he carved three small figures for the Shrine of St. Dominic. By 1496, he had moved to Rome, a city that would become central to his career. An early work from this period, a statue of Bacchus (1496-1497), commissioned by Cardinal Raffaele Riario, demonstrated his ability to imbue classical subjects with a unique vitality and psychological depth. Though the Cardinal ultimately rejected it, the Bacchus found a home in the collection of the banker Jacopo Galli.

It was in Rome that Michelangelo created one of his most celebrated masterpieces, the Pietà (1498-1499). Commissioned by the French Cardinal Jean de Bilhères-Lagraulas for his tomb in St. Peter's Basilica, this sculpture depicts the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Christ. The work is renowned for its breathtaking technical virtuosity, the delicate rendering of flesh and drapery, and the profound pathos conveyed through the Virgin's youthful, sorrowful face. Unusually, Michelangelo signed this work on the sash across Mary's breast, reportedly after overhearing pilgrims attribute it to another sculptor. The Pietà established the young artist, then only in his early twenties, as a leading sculptor of his time.

Florence and the Colossus: The David

In 1501, Michelangelo returned to Florence, where the political climate had somewhat stabilized with the establishment of a republic. He was commissioned by the Opera del Duomo (Cathedral Works) to create a colossal statue of the biblical hero David. The commission was particularly challenging as it involved working with a massive block of Carrara marble that had been partially carved and abandoned by other artists, Agostino di Duccio and Antonio Rossellino, decades earlier. Many considered the block spoiled.

Over the next three years, from 1501 to 1504, Michelangelo worked in secrecy, transforming the flawed marble into an icon of Renaissance art. His David is not the boyish figure often depicted by earlier artists like Donatello or Verrocchio, but a powerful, muscular young man, captured in the tense moment before his battle with Goliath. The statue's anatomical precision, its contrapposto stance, and the intense, watchful expression on David's face convey a sense of coiled energy and heroic resolve. Standing over 17 feet tall, the David became a symbol of Florentine liberty and defiance. Its placement in front of the Palazzo Vecchio, the seat of Florentine government, further underscored its civic importance. The sheer audacity and perfection of the David solidified Michelangelo's reputation as a sculptor of unparalleled genius.

The Sistine Chapel Ceiling: A Herculean Task

In 1505, Pope Julius II, an ambitious and formidable patron, summoned Michelangelo back to Rome. Initially, the Pope commissioned Michelangelo to design and sculpt his monumental tomb, a project that would become a source of immense frustration and disappointment for the artist over the next four decades, repeatedly scaled down and altered. However, in 1508, Julius II presented Michelangelo with a different, and arguably even more daunting, commission: to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican.

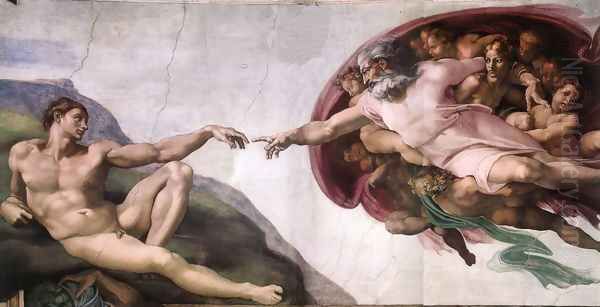

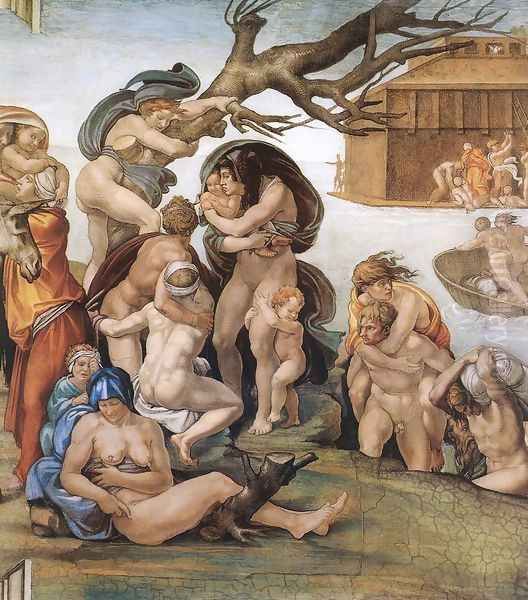

Michelangelo, who always considered himself primarily a sculptor, was reluctant to take on such a vast painting project. He even suspected that rivals, perhaps the architect Donato Bramante, had suggested him for the job in the hope that he would fail. Despite his reservations, he accepted the challenge. The original plan called for figures of the twelve apostles, but Michelangelo negotiated a more complex and ambitious scheme. Over four arduous years, from 1508 to 1512, working on specially designed scaffolding high above the chapel floor, often in uncomfortable and physically demanding conditions, he painted a vast cycle of frescoes depicting nine scenes from the Book of Genesis.

These scenes, including the iconic Creation of Adam, The Fall and Expulsion from Paradise, and The Deluge, are framed by an elaborate painted architectural structure. Surrounding these central narratives are monumental figures of Prophets and Sibyls, the ancestors of Christ (Ignudi), and other biblical scenes. The Sistine Chapel ceiling is a triumph of artistic vision and technical skill, showcasing Michelangelo's mastery of human anatomy, dynamic composition, and expressive power. The figures are imbued with a sense of terribilità – an awesomeness and sublime power that became a hallmark of his style.

Papal Projects and Architectural Endeavors

Following the completion of the Sistine ceiling, Michelangelo continued to work on Pope Julius II's tomb, though with many interruptions and revisions. The most famous sculpture completed for this project is the powerful Moses (c. 1513-1515), which now forms the centerpiece of the much-reduced tomb in the Church of San Pietro in Vincoli, Rome. Other figures intended for the tomb, such as the Rebellious Slave and the Dying Slave (both c. 1513-1516, now in the Louvre), further demonstrate his ability to convey intense emotion and physical struggle.

Under the Medici Popes, Leo X and Clement VII, Michelangelo undertook significant architectural and sculptural projects in Florence. For the Basilica of San Lorenzo, the Medici family church, he designed the facade (though it was never built) and, more importantly, the New Sacristy, also known as the Medici Chapel (1520-1534). This chapel, intended as a mausoleum for members of the Medici family, is a harmonious integration of architecture and sculpture. It features the monumental tombs of Giuliano de' Medici, Duke of Nemours, and Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, adorned with allegorical figures of Day and Night, and Dusk and Dawn, respectively. These sculptures are among his most profound and enigmatic works, conveying a deep sense of melancholy and the passage of time. He also designed the Laurentian Library (begun 1525) at San Lorenzo, with its innovative and dramatic vestibule and staircase.

The Last Judgment: A Vision of Apocalypse

In 1534, Michelangelo left Florence for the last time and settled permanently in Rome. Pope Clement VII, shortly before his death, commissioned him to paint a fresco of the Last Judgment on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. The work was completed under Pope Paul III and unveiled in 1541, nearly thirty years after Michelangelo had finished the ceiling.

The Last Judgment is a vast and terrifying vision of the Second Coming of Christ and the apocalypse. Dominating the composition is a powerful, muscular Christ, depicted as an implacable judge. Surrounding him are saints, martyrs, and throngs of resurrected souls, some ascending to heaven, others dragged down to hell by demons. The fresco is a radical departure from traditional representations of the subject and from the High Renaissance ideals of harmony and balance that characterized the ceiling. Its swirling, dynamic composition, the contorted and often nude figures, and the overwhelming sense of divine wrath created a profound impact. Michelangelo controversially included his own likeness in the flayed skin held by Saint Bartholomew, a poignant expression of his own spiritual anxieties. The work sparked considerable controversy, particularly for its extensive nudity, which was deemed inappropriate for such a sacred space. Years later, after Michelangelo's death, the artist Daniele da Volterra was commissioned to paint draperies over some of the figures, earning him the nickname "Il Braghettone" (the breeches-maker).

Later Years, St. Peter's Basilica, and Poetry

In his later years, Michelangelo focused increasingly on architecture and poetry. In 1546, he was appointed chief architect of St. Peter's Basilica, a position he held until his death. He returned to Bramante's original centralized plan, simplifying and strengthening it, and designed the magnificent dome, one of the most iconic features of the Roman skyline. Though the dome was completed after his death by Giacomo della Porta, with some modifications, its essential form and grandeur are Michelangelo's.

His late sculptures, such as the Florentine Pietà (c. 1547-1555, also known as The Deposition), which he intended for his own tomb and in which the figure of Nicodemus is a self-portrait, and the Rondanini Pietà (1552-1564), which he worked on until days before his death, are characterized by a deeply spiritual quality and an increasing abstraction of form. The Rondanini Pietà, in particular, with its elongated, dematerialized figures, reflects a profound spiritual introspection and a departure from his earlier emphasis on physical perfection. This "non-finito" (unfinished) quality in some of his late works has been interpreted as a deliberate artistic choice, conveying a sense of spiritual struggle and transcendence.

Michelangelo was also a gifted poet, writing over 300 sonnets and madrigals throughout his life. His poetry explores themes of love (often Neoplatonic, addressed to figures like Tommaso de' Cavalieri and Vittoria Colonna), beauty, art, and spirituality, offering intimate insights into his complex inner world.

Artistic Style and Innovations

Michelangelo's artistic style is characterized by several key elements. His profound understanding of human anatomy, honed through dissections (which he was granted permission to conduct early in his career), allowed him to depict the human body with unparalleled accuracy and power. He saw the body, particularly the male nude, as the ultimate vehicle for expressing human emotion and divine aspiration. His figures often possess a monumental quality and a sense of terribilità – a sublime, awe-inspiring power that can be both beautiful and terrifying.

He had a sculptor's approach even to painting, with figures often appearing as if carved from stone, possessing a strong sense of volume and three-dimensionality. His use of dynamic, often contorted poses (contrapposto and figura serpentinata) imbued his figures with a sense of movement and energy. The "non-finito" or unfinished state of some of his sculptures, whether intentional or due to circumstance, became an expressive device, suggesting the struggle of the form to emerge from the stone or the limitations of art in capturing the ideal.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Michelangelo's long and prolific career brought him into contact, and often conflict, with many of the leading artists and patrons of his time. His relationship with Leonardo da Vinci was one of rivalry. The two titans were commissioned to paint battle scenes on opposite walls of the Sala del Gran Consiglio in Florence's Palazzo Vecchio (Michelangelo's Battle of Cascina and Leonardo's Battle of Anghiari), though neither fresco was completed. Their artistic temperaments and approaches differed significantly: Leonardo, older and more scientific in his inquiries; Michelangelo, more solitary and driven by an intense, almost spiritual, passion.

Raphael Sanzio, another giant of the High Renaissance, was a younger contemporary. While Raphael admired and learned from Michelangelo's work (his figures in the Vatican Stanze, such as in The School of Athens, show increased monumentality after he saw the Sistine ceiling), there was also an element of competition. Michelangelo, known for his solitary working habits, sometimes accused Raphael of plagiarizing his ideas, a charge likely fueled by their contrasting personalities – Raphael being more affable and adept at managing a large workshop.

His relationship with patrons, particularly Pope Julius II, was often stormy. Michelangelo's fierce independence and artistic integrity clashed with the demands and whims of powerful individuals. Yet, these challenging relationships also spurred some of his greatest achievements. He also had a complex relationship with Titian, the leading figure of the Venetian school. While in Rome, Titian's Danaë was shown to Michelangelo, who praised its color and style but reportedly remarked to Vasari that it was a pity that in Venice they did not learn to draw well from the beginning. This highlights the ongoing debate between disegno (design and drawing, championed in Florence and Rome) and colorito (color, prioritized in Venice).

Other artists of the era include his teacher Ghirlandaio, and figures like Perugino (Raphael's teacher), Luca Signorelli (whose frescoes at Orvieto Cathedral, with their powerful nudes, influenced Michelangelo), Andrea del Sarto, Fra Bartolommeo, and later Mannerist artists like Bronzino, Pontormo, and Rosso Fiorentino, who were profoundly impacted by Michelangelo's stylistic innovations. Sculptors like Benvenuto Cellini were also his contemporaries. His friend and biographer Giorgio Vasari, himself an artist and architect, provided invaluable, if sometimes biased, accounts of Michelangelo's life and works.

Personal Life and Character

Michelangelo was a man of intense, often solitary, habits. He never married and had no children, dedicating his life almost entirely to his art. He was known for his frugal lifestyle, often living in simple conditions despite his fame and the considerable sums he earned. He was deeply religious, and his faith became increasingly profound in his later years, reflected in his poetry and late artworks.

His temperament was famously irascible and melancholic. He was fiercely protective of his artistic autonomy and could be critical and dismissive of others. However, he also formed deep and lasting friendships. His platonic but intensely emotional relationships with the young Roman nobleman Tommaso de' Cavalieri and the poet Vittoria Colonna, Marchesa of Pescara, are well-documented through his letters and sonnets. These relationships provided him with intellectual and spiritual companionship.

Throughout his life, Michelangelo suffered from various health problems, including what is believed to have been kidney stones and gout, likely exacerbated by his demanding work and simple diet. Politically, he was a Florentine republican at heart, though he navigated the complex and often treacherous world of papal and Medici patronage with a degree of pragmatism. He was involved in the defense of Florence during the siege of 1529-30, serving as governor of fortifications.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Michelangelo's impact on Western art is immeasurable. He, along with Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael, is considered one of the three giants of the High Renaissance. His work set new standards for anatomical accuracy, emotional expression, and technical virtuosity. His stylistic innovations, particularly the emphasis on muscularity, dynamic movement, and psychological intensity, were instrumental in the development of Mannerism, the artistic style that followed the High Renaissance. Artists like Rosso Fiorentino, Pontormo, Bronzino, and later El Greco, all drew inspiration from his powerful forms and expressive distortions.

His influence extended far beyond his immediate successors. Sculptors like Gian Lorenzo Bernini in the Baroque era looked to Michelangelo's dynamism and emotional power. Auguste Rodin, in the 19th century, deeply admired Michelangelo's "non-finito" works and his ability to convey raw emotion through the human form. Architects, painters, and sculptors for centuries have studied his works, drawing inspiration from his technical mastery and profound artistic vision.

Michelangelo was revered in his own lifetime as "Il Divino" (The Divine One), a testament to the awe his contemporaries felt for his genius. He was the first Western artist whose biography was published while he was still alive (two, in fact, by Vasari and Ascanio Condivi). His death in Rome in 1564 was mourned throughout Italy. Though he died in Rome, his body was secretly transported back to his beloved Florence, where he was buried with great honor in the Basilica di Santa Croce.

Conclusion

Michelangelo Buonarroti was more than just an artist; he was a force of nature, a creative powerhouse whose work transcended the boundaries of his time. His sculptures seem to breathe with life, his paintings pulsate with divine energy, and his architecture commands space with majestic authority. Through his unwavering dedication to his craft, his profound understanding of the human condition, and his relentless pursuit of an ideal beauty that was both physical and spiritual, Michelangelo created a body of work that remains a cornerstone of artistic achievement. His legacy is not merely in the stone he carved or the walls he painted, but in the enduring power of his art to move, inspire, and challenge humanity across the ages.