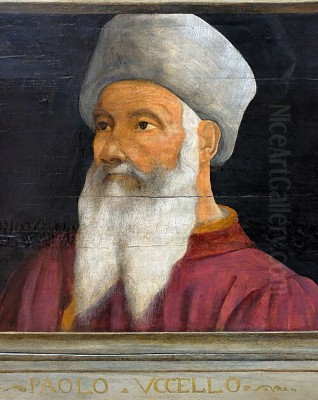

Paolo Uccello, born Paolo di Dono around 1397 in Pratovecchio, near Florence, stands as one of the most distinctive and intriguing figures of the Early Italian Renaissance. While celebrated primarily as a painter, he was also deeply engrossed in mathematics, particularly the burgeoning science of linear perspective. This fascination shaped his artistic output profoundly, leaving behind a body of work admired for its technical innovation, decorative flair, and sometimes startling originality. His adopted surname, Uccello, meaning "bird" in Italian, reportedly stemmed from his fondness for painting animals, especially birds, adding a layer of personal charm to his historical identity. He navigated a period of intense artistic transformation, bridging the decorative elegance of Late Gothic art with the rational, space-defining principles of the Renaissance.

Early Life and Florentine Foundations

Uccello's origins reflect the social fabric of his time. His father, Dono di Paolo, was a barber-surgeon, a respected profession in Florence, while his mother, Antonia di Giovanni del Beccuto, came from a noble Florentine family. This background placed him within the vibrant artisan and intellectual milieu of the city. His artistic journey began formally around 1407, when, at the young age of about ten, he was apprenticed to the renowned sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti. This was a pivotal experience, occurring during the period Ghiberti was working on the famous bronze doors for the Florence Baptistery, known as the "Gates of Paradise."

In Ghiberti's bustling workshop, Uccello would have absorbed the prevailing International Gothic style, characterized by its elegant lines, decorative richness, and detailed observation of nature. He worked alongside other talented young artists, including the sculptor Donatello, with whom he formed a lasting friendship. This early exposure to sculpture and the intricate demands of bronze casting likely honed his sense of form and precision. He was admitted to the painters' guild, the Arte dei Medici e Speziali, in 1415, signalling his establishment as an independent master.

The Seduction of Perspective

While grounded in the Gothic tradition, Uccello became captivated by the revolutionary ideas concerning perspective that were circulating in Florence, largely pioneered by the architect Filippo Brunelleschi. Brunelleschi's experiments with linear perspective, demonstrating how to create a mathematically convincing illusion of three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional surface, profoundly impacted the artistic landscape. Uccello embraced these concepts with an almost obsessive fervour, dedicating immense effort to mastering the complexities of vanishing points, foreshortening, and spatial recession.

According to the 16th-century biographer Giorgio Vasari, whose Lives of the Artists provides colourful, if sometimes embellished, accounts, Uccello's dedication to perspective was all-consuming. Vasari recounts how Uccello would stay up late into the night, grappling with perspective problems, much to the exasperation of his wife. When she would call him to bed, he would reportedly exclaim about the sweetness of "la dolce prospettiva" (sweet perspective). These anecdotes, while perhaps exaggerated, underscore the intense intellectual curiosity that drove Uccello to explore the geometric underpinnings of visual representation. This focus distinguished him from many contemporaries who prioritized naturalism or emotional expression.

His studies were not merely theoretical; they were deeply integrated into his artistic practice. He meticulously constructed complex spatial environments, often populating them with figures and objects rendered with sharp, geometric clarity. This mathematical approach sometimes led to results that appeared stylized or even unnaturalistic to later eyes, but they represented a determined effort to apply scientific principles to art. He became particularly adept at depicting complex geometric forms like the mazzocchio, the multifaceted Florentine headdress, often using it as a vehicle to display his perspectival skill.

Artistic Style: A Bridge Between Eras

Uccello's artistic style is unique, representing a fascinating synthesis of old and new. He retained elements of the Late Gothic style learned in Ghiberti's workshop, evident in his love for decorative patterns, rich colours, and detailed rendering of armour, fabrics, and natural elements. His compositions often possess a tapestry-like quality, filled with intricate details that delight the eye. However, this decorative sensibility is overlaid with, and sometimes subordinated to, his rigorous application of linear perspective.

Unlike contemporaries such as Masaccio, who used perspective to enhance the realism and dramatic weight of his figures, Uccello often seemed more interested in perspective as an end in itself. His figures can sometimes appear secondary to the complex spatial architecture he creates, acting almost as markers within a geometric grid. This can result in a certain stiffness or lack of psychological depth in his figures compared to the burgeoning humanism seen in the work of artists like Fra Angelico or Filippo Lippi.

His approach led to compositions that are visually striking but can feel somewhat frozen or artificial. Horses might be rendered in unconventional colours, landscapes simplified into geometric planes, and figures arranged according to perspectival logic rather than narrative flow. This emphasis on structure and pattern over naturalistic representation has led some critics, including Vasari, to suggest that his obsession with perspective hindered his development in rendering lifelike figures and animals. Nonetheless, this very uniqueness makes his work compelling and marks him as a transitional figure, grappling with the shift from medieval artistic conventions to Renaissance rationalism.

Masterworks and Major Commissions

Paolo Uccello's reputation rests on a relatively small number of surviving works, several of which are considered masterpieces of the Early Renaissance. Among his most famous creations is the _The Battle of San Romano_ triptych, likely commissioned by the Bartolini Salimbeni family of Florence around the 1430s or 1440s (though later owned by the Medici). Originally consisting of three large panels depicting stages of the Florentine victory over Sienese forces in 1432, the paintings are now dispersed among the National Gallery in London, the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, and the Louvre Museum in Paris.

These panels are tour-de-forces of perspective and composition. Uccello uses foreshortened lances, fallen soldiers, and receding landscapes to create a dynamic, if somewhat staged, sense of depth. The gleaming armour, colourful banners, and stylized horses contribute to a scene that is both a historical narrative and a complex decorative arrangement. The careful placement of broken lances on the ground forms an orthogonal grid, explicitly demonstrating the principles of perspective. While celebrated for their technical brilliance, the panels also exemplify the critique of Uccello's work: the figures can seem like mannequins arranged within a geometric exercise.

Another significant work is the fresco _The Flood and Recession of the Flood_ (c. 1447-1448), painted in the Green Cloister (Chiostro Verde) of Santa Maria Novella in Florence. This dramatic, large-scale lunette demonstrates Uccello's mastery of perspective in depicting architectural space and human figures in extreme situations. The scene is crowded and chaotic, showing desperate figures clinging to a receding ark during the deluge, rendered with powerful foreshortening and a stark, almost monochrome palette (verdaccio underpainting, giving the cloister its name) that enhances the grim atmosphere.

Uccello also created notable works for Florence Cathedral (Santa Maria del Fiore). Around 1436, he painted the colossal equestrian monument fresco honouring the English mercenary Sir John Hawkwood (Giovanni Acuto). Designed to simulate a three-dimensional sculpture seen from below, it is a prime example of his perspectival interests applied to monumental commemoration. He also designed stained-glass windows for the cathedral's drum (oculi featuring the Nativity, Resurrection, Ascension, and Annunciation) and painted the four heads of prophets or evangelists on the face of the cathedral's clock in 1443, employing illusionistic perspective.

His fascination with chivalric themes and animals is evident in _St. George and the Dragon_. Two versions exist, one in the National Gallery, London (c. 1470), and another, possibly earlier one, in the Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris (c. 1440-1450). These paintings combine fairy-tale elements with his characteristic perspectival structuring of the landscape and stylized rendering of the figures and the mythical beast.

Uccello also undertook commissions outside Florence. He worked in Venice from around 1425 to 1431, where he created mosaics for the facade of St. Mark's Basilica. Unfortunately, little of this work survives, and Vasari reports that Uccello left Venice somewhat discredited, possibly due to difficulties with the mosaic medium or unfinished work. He also worked in Padua around 1445, painting frescoes of giants in the Casa Vitaliani, which are now lost but were noted by contemporaries like Andrea Mantegna.

Relationships with Contemporaries

Uccello's long career placed him at the heart of the Florentine art world during a period of extraordinary creativity. His primary training under Lorenzo Ghiberti connected him to the leading edge of sculpture and design. His enduring friendship with Donatello, arguably the most influential sculptor of the Early Renaissance, provided a vital link to the development of realism and classical ideals, even if Uccello pursued a different path. They likely exchanged ideas throughout their careers, and Donatello's powerful naturalism may have offered a counterpoint to Uccello's more stylized approach.

His engagement with perspective inevitably brought him into the orbit of Filippo Brunelleschi, the architect who codified linear perspective. While direct collaboration isn't documented beyond the context of the Cathedral works, Brunelleschi's theories were fundamental to Uccello's practice. He also worked alongside or was aware of the innovations of Masaccio, whose frescoes in the Brancacci Chapel demonstrated a revolutionary use of perspective combined with monumental, psychologically resonant figures.

Other significant contemporaries included Fra Angelico, whose work combined Gothic grace with Renaissance spatial awareness but focused on spiritual serenity rather than technical display. Andrea del Castagno shared Uccello's interest in strong contours and anatomical study, while Domenico Veneziano explored the effects of light and colour. Uccello's work, particularly his exploration of perspective, undoubtedly influenced Piero della Francesca, another artist deeply interested in mathematics and geometry, who achieved a more harmonious synthesis of perspective, form, and light. The theorist Leon Battista Alberti, whose treatise De Pictura (On Painting) codified the principles of perspective, was also active during this period, providing a theoretical framework that Uccello explored visually. He may also have known Masolino da Panicale, who collaborated with Masaccio. Despite these connections, Uccello remained something of an artistic individualist. He did not establish a workshop that fostered a distinct school or train prominent pupils in his specific manner. His influence was transmitted more through the provocative nature of his visual experiments than through direct teaching.

Challenges and Later Life

Despite his innovative talent, Uccello's career was not without its difficulties. His intense focus on perspective, while groundbreaking, may have limited his appeal to patrons seeking more conventional or emotionally engaging works. Vasari suggests that this single-mindedness led him to neglect other aspects of his art and potentially hindered his financial success. Records indicate that Uccello lived modestly, and in his later years, he declared himself "old and without means" in tax returns.

The criticism regarding his unfinished mosaic work in Venice also suggests potential professional setbacks. Furthermore, his unique style, which didn't neatly align with the burgeoning classical realism favoured by some patrons and artists, might have made him seem eccentric or difficult. Vasari portrays him as somewhat solitary and reclusive in his later years, deeply immersed in his intellectual pursuits.

He appears to have remained unmarried for much of his life, though records indicate he did marry late, possibly to Selvaggia dei Ciramelli, and had children. His daughter Antonia Uccello (born 1456) became a Carmelite nun and was noted by Vasari as being a painter herself, though none of her work is known to survive. Paolo Uccello continued to work into his old age, but his output seems to have diminished. He died in Florence in 1475, at the age of 78, and was buried in the church of Santo Spirito.

Legacy and Influence

Paolo Uccello's legacy is complex and has evolved over time. In his own era and shortly after, he was respected for his technical skill, particularly in perspective, but also criticized for the perceived shortcomings in naturalism and grace. Vasari's influential biography cemented the image of Uccello as a brilliant but eccentric artist whose obsession ultimately limited his greatness. However, his pioneering work laid crucial groundwork for subsequent generations.

Artists like Piero della Francesca absorbed and built upon Uccello's perspectival explorations, integrating them into a more serene and monumental classical style. Andrea Mantegna, known for his own daring experiments with foreshortening and perspective, likely knew Uccello's work in Padua. Even Leonardo da Vinci, who perfected the use of atmospheric perspective and sfumato, would have studied the linear perspective principles that Uccello helped establish. Northern European artists like Albrecht Dürer, who travelled to Italy and wrote treatises on geometry and perspective, were also part of the lineage that benefited from the early Italian experiments.

While Uccello did not found a school, his influence resurfaced significantly in the 20th century. Modern artists, particularly the Cubists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, found resonance in Uccello's geometric stylization, his fracturing of forms, and his emphasis on structure over illusionistic realism. The Surrealists also admired the dreamlike, sometimes unsettling quality of his compositions, such as the otherworldly landscapes in St. George and the Dragon or the staged intensity of The Battle of San Romano. Art historians and critics in the 20th century re-evaluated Uccello, appreciating his formal innovations and recognizing him as a highly original master whose work anticipated later artistic developments.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Paolo Uccello remains a captivating figure in the history of art. He was a man of his time, trained in the Late Gothic tradition, yet driven by an intense, almost obsessive curiosity about the new scientific and mathematical approaches to representation emerging in the Renaissance. His dedication to mastering perspective produced works of stunning technical ingenuity and visual complexity, even if they sometimes sacrificed naturalism for geometric rigor.

His unique blend of decorative sensibility and structural logic created a style that stood apart from his contemporaries. While he faced criticism and perhaps struggled for consistent patronage, his relentless exploration of space and form provided invaluable lessons for subsequent artists. Uccello's work serves as a powerful reminder that the Renaissance was not a monolithic movement but a period of diverse experimentation, where artists grappled with tradition and innovation in highly personal ways. His "sweet perspective" may have been an obsession, but it was one that fundamentally altered the course of Western art, leaving behind a legacy that continues to intrigue and inspire.