The name William Linton echoes through nineteenth-century art history, yet it often evokes distinct, though sometimes overlapping, personas. Primarily, we encounter William Linton (1791-1876), a respected British landscape painter celebrated for his classical compositions and evocative depictions of European scenery. However, the historical record also prominently features William James Linton (1812-1897), a highly influential wood-engraver, radical political activist, writer, and poet, whose life and work were deeply intertwined with the socio-political currents of his time. This exploration will delve into the lives and contributions of these figures, paying close attention to their artistic styles, representative works, collaborations, and the broader cultural milieu in which they operated, ensuring that the distinct contributions of each are appreciated.

William Linton (1791-1876): The Classical Landscape Painter

William Linton, born in 1791, established himself as a significant figure in the British school of landscape painting. His artistic journey was characterized by a deep appreciation for classical aesthetics, often drawing inspiration from the grand tradition of European landscape art. His career unfolded during a period when landscape painting in Britain was reaching new heights, with contemporaries like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable revolutionizing the genre, though Linton's approach often hewed more closely to the idealized visions of earlier masters such as Claude Lorrain and Nicolas Poussin.

Artistic Style and Grand Tours

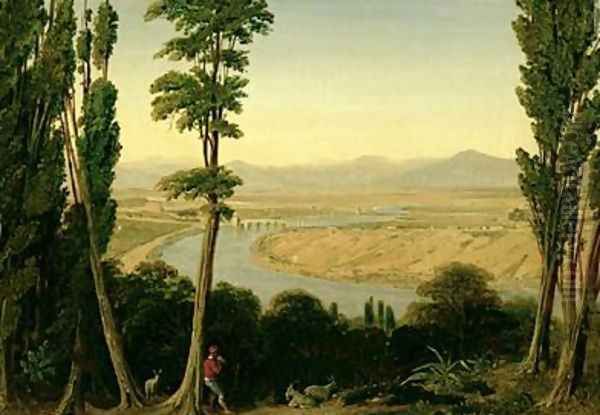

Linton's style is often described as embodying an "unaffected truthfulness," a quality he sought to capture in his depictions of nature, albeit filtered through a classical lens. His artistic development was significantly shaped by his travels. Journeys through Italy, Greece, and Malta provided him with a rich repository of subjects and a profound understanding of classical landscapes, ancient ruins, and the interplay of light and atmosphere characteristic of the Mediterranean world. These experiences infused his work with a sense of historical grandeur and picturesque beauty.

He was particularly adept at capturing the essence of the places he visited, translating his observations into carefully composed canvases. His paintings often feature expansive views, meticulously rendered architectural elements, and a harmonious balance of color and light. While he worked in oils, Linton was also a skilled watercolorist, a medium that allowed for spontaneity and a delicate rendering of atmospheric effects, popular among British artists of the period.

Representative Works and Publications

Among William Linton's notable works is "The Temple of Female Fortune with the Acqua Felice," painted between 1849 and 1852. This piece exemplifies his mastery of classical landscape, combining architectural accuracy with an idealized vision of the Roman Campagna. Such works demonstrated his deep engagement with the historical and cultural resonance of the sites he depicted.

Beyond his painted oeuvre, Linton also contributed to the visual culture of his time through publications. His book, "Scenery of Greece and its Islands" (1856), showcased his artistic talents and his scholarly interest in the classical world, offering viewers a visual journey through historically significant landscapes. Another publication, "Ancient and Modern Colours" (1852), suggests an engagement with the technical and theoretical aspects of painting, reflecting a comprehensive approach to his artistic practice. His works were regularly exhibited at prestigious venues, including the Royal Academy in London, a testament to his standing within the British art establishment.

Linton's dedication to classical ideals and his skillful portrayal of European landscapes secured him a respectable place among British painters of the nineteenth century. His work offers a vision of nature and history that is both grand and intimately observed, reflecting the enduring appeal of the classical tradition in an age of romanticism and burgeoning realism.

A Necessary Distinction: William James Linton (1812-1897)

While William Linton the landscape painter carved out his niche, another formidable artistic and political figure, William James Linton (often referred to as W. J. Linton), born in London in 1812, rose to prominence as one of the most important wood-engravers of the Victorian era. His career was markedly different, characterized by a fervent commitment to radical politics, a prolific output as an engraver and writer, and a significant influence on the art of illustration and printmaking on both sides of the Atlantic. Much of the detailed information regarding political activism, specific collaborations in print, and a later move to America points distinctly to W. J. Linton.

William James Linton: Master Engraver, Political Radical, and Prolific Writer

William James Linton's life was a dynamic fusion of artistic craftsmanship and unwavering political idealism. Apprenticed to the wood-engraver G. W. Bonner, he quickly mastered the intricacies of the medium. Wood engraving, a relief printing technique where the image is incised into the end-grain of a block of wood, was the dominant method for illustrating books, newspapers, and periodicals throughout the 19th century, and Linton became one of its most articulate and skilled practitioners.

The Art and Craft of Wood Engraving

Linton was not merely a technician; he was a passionate advocate for the artistic potential of wood engraving. He championed the "white line" technique, famously pioneered by Thomas Bewick, where the artist thinks in terms of cutting white lines out of a black field, allowing for subtle tonal gradations and expressive power. He believed that the engraver should be an interpretive artist, not just a slavish copyist of a designer's drawing. This philosophy often put him at odds with publishers and artists who sought mere reproduction.

His emphasis on design, materials, and production methods had a profound impact on his students and the subsequent generation of engravers. He believed in the unity of art and craft, a sentiment that would later resonate with the Arts and Crafts Movement, spearheaded by figures like William Morris, with whom Linton corresponded, discussing the relationship between art and craftsmanship.

Collaborations and Illustrated Works

W. J. Linton's skill led to numerous collaborations. Early in his career, he partnered with John Orrin Smith, a fellow engraver. Together, and independently, Linton contributed extensively to the burgeoning illustrated press. He provided engravings for influential publications such as the Illustrated London News, a groundbreaking periodical that brought visual reportage to a mass audience. His subjects were diverse, ranging from current events and social scenes to literary illustrations.

He engraved works for many prominent artists of his day. For instance, he was involved in projects that included illustrations by W. L. Leitch, Duncan, and Dodgson (likely Charles Dodgson, better known as Lewis Carroll, though his primary artistic output was photography, he did draw). Linton also engraved illustrations for editions of Charles Dickens's "A Christmas Carol." His firm was responsible for engraving some of the iconic Pre-Raphaelite designs for the Moxon Tennyson (1857), including works by Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais, though the artists were sometimes dissatisfied with the translation of their intricate drawings into engraved lines.

His own illustrated books, such as "Poems and Pictures" and "The Ferns of the English Lake Country, with a List of Varieties" (1876), showcased his dual talents as an artist and writer. He also produced "Thirty Pictures by Deceased British Artists" and "The English Republic," a collection of his political writings often illustrated with his own engravings.

Unwavering Political Convictions

W. J. Linton was a man of deeply held radical political beliefs. He was a fervent Chartist, advocating for universal male suffrage and other democratic reforms in Britain. His commitment to republicanism was profound, influenced by European revolutionaries like Giuseppe Mazzini, with whom he formed a close friendship. Linton actively participated in political reform movements, using his skills as a writer and publisher to disseminate his ideas.

He edited and published several radical journals, including "The National: A Library for the People" and, most notably, "The English Republic" (1851-1855). Through these publications, he promoted his vision of a democratic and egalitarian society. His political activism was not without personal cost, contributing to financial difficulties and a sense of disillusionment with the political climate in Britain. His writings, poetry, and essays were often infused with his revolutionary and socialist ideals, drawing on a Romantic print culture that included revolutionary pamphlets and the uniquely illustrated works of William Blake, whom Linton admired.

Emigration to America and Continued Influence

In 1866 (some sources state 1867), facing financial hardship and perhaps seeking a more receptive environment for his ideals, W. J. Linton emigrated to the United States. He settled near New Haven, Connecticut, in a farmhouse he named "Appledore." His choice of New Haven was symbolic, as it had historically been a refuge for regicides who had condemned King Charles I.

In America, Linton continued his work as an engraver, writer, and teacher. He taught wood engraving at the Cooper Union in New York City, where his emphasis on the artistic integrity of the medium influenced a new generation of American engravers. He established a private press at Appledore, from which he issued various publications, including his own poetry, such as "Wind-Falls" and "Ireland for the Irish."

His most significant contributions during his American years were arguably his scholarly works on the history of wood engraving. "The Masters of Wood Engraving" (1889), a lavishly produced folio volume, and "History of Wood Engraving in America" (1882) became standard texts. In these, he assessed the work of past masters like Albrecht Dürer and Hans Holbein, celebrated Thomas Bewick, and critiqued contemporary trends, sometimes clashing with the "New School" of American wood engravers (like Timothy Cole and Henry Wolf) whom he felt were overly focused on reproductive fidelity at the expense of artistic interpretation.

Connections with Contemporaries

Throughout his long career, W. J. Linton interacted with a vast network of artists, writers, and political figures. His early association with John Orrin Smith was formative. His engraving work brought him into contact with leading illustrators like John Gilbert and Birket Foster. His political activities connected him with Chartists like Feargus O'Connor and William Lovett, and international republicans like Mazzini and Alexandre Auguste Ledru-Rollin. He was part of a vibrant London bohemia that included artists, writers, and émigrés.

His influence extended to younger artists who shared his commitment to the artistic quality of illustration, such as Walter Crane and Frederic Leighton (though Frederic Brigg was mentioned in the initial information, Frederic Leighton is a more prominent contemporary figure whose work might have been engraved, or perhaps the reference was to a lesser-known engraver). Crane, in particular, acknowledged Linton's impact on his understanding of design and print. Linton's relationship with William Morris, though sometimes strained by differing approaches, was rooted in a shared respect for craftsmanship and a desire for social change. He also knew figures like the Dalziel Brothers, who ran one of the largest and most commercially successful wood-engraving firms in London, often representing a more commercial approach to the medium than Linton's own. The prolific output of French illustrator Gustave Doré, whose works were widely circulated in Britain, also formed part of the visual landscape Linton operated within.

Later Life and Legacy

William James Linton passed away in New Haven in 1897. His legacy is multifaceted. As a wood-engraver, he was one of the last great practitioners of a craft that was soon to be superseded by photomechanical reproduction processes. He fought to elevate its status from a mere trade to a fine art. His writings on the subject remain valuable historical resources.

As a political activist, he was an unwavering voice for democratic and republican ideals, a tireless propagandist for social justice. Though his political goals were not always realized in his lifetime, his commitment to them was absolute. His poetry and prose, though perhaps less widely read today, offer a window into the mind of a passionate idealist. He was, in essence, a Victorian polymath – an artist, craftsman, poet, journalist, and political firebrand whose life and work offer a rich tapestry of 19th-century art and radicalism.

Conclusion: Two Lintons, Distinct Legacies

In reflecting on William Linton, it is essential to distinguish between the classical landscape painter (1791-1876) and the radical wood-engraver and writer, William James Linton (1812-1897). The former, William Linton, contributed to the tradition of British landscape art with his refined depictions of European scenery, earning acclaim for his "unaffected truthfulness" and classical compositions. His works, such as "The Temple of Female Fortune," and his published "Scenery of Greece," remain as testaments to his skill and his dedication to the picturesque and historical.

William James Linton, on the other hand, carved a more turbulent and arguably more broadly impactful path. His mastery of wood engraving, his fervent political activism, his prolific writings, and his influential teaching career left an indelible mark on the art of illustration and the radical political discourse of his era. From his Chartist beginnings and collaborations with London's artistic elite to his later years in America championing the history and practice of wood engraving through works like "The Masters of Wood Engraving," W. J. Linton embodied the spirit of a restless innovator and a committed idealist.

Both men, in their respective spheres, contributed to the rich cultural fabric of the nineteenth century. Understanding their distinct careers and contributions allows for a fuller appreciation of the diverse artistic and intellectual currents that shaped their world and continue to inform our understanding of art history.