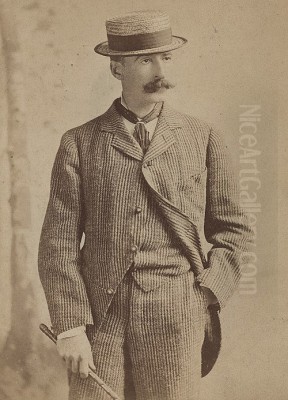

Winslow Homer stands as one of the towering figures in American art history. Born in Boston, Massachusetts, on February 24, 1836, and passing away in his coastal Maine studio at Prout's Neck on September 29, 1910, Homer's life spanned a period of profound transformation in the United States. He emerged as a preeminent painter and illustrator, primarily celebrated for his powerful depictions of the natural world, particularly the sea, as well as evocative scenes of American rural life and the stark realities of the Civil War. Working masterfully in both oil and watercolor, Homer forged a distinctly American artistic identity, marked by direct observation, technical brilliance, and a deep, often unsentimental, engagement with his subjects.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Winslow Homer's journey into art began in a supportive, though not formally artistic, household. His father, Charles Savage Homer Sr., was a hardware merchant, providing a stable middle-class background. More direct influence came from his mother, Henrietta Benson Homer. She was a gifted amateur watercolorist, recognized for her talent in flower painting. Henrietta was her son's first teacher, nurturing his nascent artistic inclinations and providing crucial early encouragement. Her own skill with watercolors likely planted the seeds for Homer's later mastery of the medium.

In 1842, when Winslow was six, the Homer family moved from Boston to the then-rural town of Cambridge, Massachusetts. This proximity to nature during his formative years undoubtedly shaped his lifelong appreciation for the outdoors. Growing up near the Charles River and the surrounding countryside provided ample opportunity for observation and sketching, activities he pursued with enthusiasm. His early drawings already showed a keen eye for detail and a natural ability to capture the essence of his surroundings.

Formal art training for Homer was minimal and largely practical. Rather than attending an art academy in his youth, his first significant step into the professional art world came around 1855, at the age of nineteen. He began a two-year apprenticeship at the Boston commercial lithography firm of John H. Bufford. This experience, though demanding and often tedious – involving the copying of designs for sheet music covers and other commercial prints – proved invaluable. It instilled in him a strong work ethic, honed his drafting skills, and gave him a fundamental understanding of printmaking processes and graphic design.

Forging an Illustrator's Career

Feeling constrained by the repetitive nature of lithographic work, Homer left Bufford's shop as soon as his apprenticeship ended in 1857. He was determined to pursue a more creative path and quickly established himself as a freelance illustrator. This marked the true beginning of his professional artistic career. He contributed illustrations to popular national magazines such as Ballou's Pictorial and, most significantly, Harper's Weekly.

In 1859, seeking greater opportunities, Homer moved to New York City, the burgeoning center of American publishing and art. He continued his successful career as a freelance illustrator, with Harper's Weekly becoming his primary outlet for over two decades. His illustrations from this period covered a wide range of subjects, capturing the pulse of contemporary American life. He depicted fashionable scenes in Boston Common, bustling city life in New York, idyllic moments of leisure in coastal resorts, and the quiet rhythms of rural existence.

Homer's work as an illustrator was crucial to his development. It trained him to observe closely, compose effectively, and tell stories visually, often with minimal elements. He developed a clear, linear style well-suited for reproduction as wood engravings. This period demanded quick thinking and adaptability, forcing him to tackle diverse subjects and meet tight deadlines. The skills acquired during these years – narrative clarity, compositional strength, and an eye for telling detail – would form the bedrock of his later painting career. He also took some initial steps toward formal painting instruction, briefly attending classes at the National Academy of Design and taking private lessons from Frédéric Rondel, a French painter.

The Crucible of War

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 profoundly impacted Homer's life and art. Harper's Weekly dispatched him to the front lines on several occasions as an artist-correspondent. Embedded with the Union Army, particularly the Army of the Potomac in Virginia, Homer witnessed firsthand the realities of military life and the grimness of conflict. He sketched soldiers in camp, on the march, and during moments of tense waiting, capturing the drudgery, camaraderie, and underlying anxiety of war.

Unlike many contemporary illustrators who focused on heroic battle charges, Homer often depicted the quieter, more personal aspects of the soldier's experience. His illustrations, translated into wood engravings for Harper's, brought the war home to readers with an unusual degree of realism and empathy. Works like Sharpshooter on Picket Duty (1862) highlighted the chillingly impersonal nature of modern warfare, while scenes of camp life humanized the ordinary soldiers.

The war years also marked Homer's serious transition from illustration to oil painting. Around 1863, he began producing paintings based on his wartime experiences. These early oils, such as Home, Sweet Home (c. 1863), depicting soldiers listening wistfully to a band playing near their camp, already showed his ability to convey complex emotions. His most acclaimed painting from this period, Prisoners from the Front (1866), portrays a confrontation between a Union officer and captured Confederate soldiers. It was lauded for its lack of overt sentimentality and its psychologically astute depiction of the war's human toll, establishing Homer as a serious painter of national consequence. The war provided him with powerful subject matter and pushed his art towards a deeper engagement with realism and human drama.

European Interlude and Shifting Focus

Following the Civil War and his initial success as a painter, Homer sought to broaden his artistic horizons. In late 1866, he traveled to France, staying for nearly a year, primarily in Paris and the artists' colony of Cernay-la-Ville. This trip exposed him to the currents of European art. While he seems not to have formally enrolled in any French academy, he undoubtedly observed the works of established masters and contemporary artists. He would have seen the realism of Gustave Courbet and the Barbizon School painters like Jean-François Millet, whose depictions of rural life resonated with his own interests.

He was also in Paris during the early stirrings of Impressionism. While it's unlikely he had significant direct contact with the core Impressionist group, he would have been aware of the new artistic directions being explored by painters like Édouard Manet and the young Claude Monet. Some scholars suggest that the brighter palettes and looser brushwork appearing in Homer's work upon his return may reflect an absorption of these contemporary French trends, particularly the emphasis on capturing light and atmosphere outdoors.

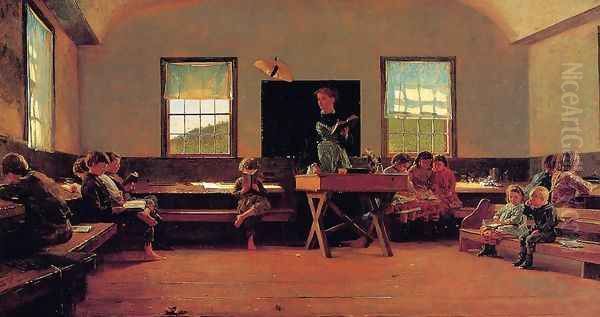

Upon returning to the United States in late 1867, Homer gradually shifted his focus away from illustration towards painting full-time, although he continued to accept illustration commissions sporadically into the 1870s. His subject matter moved away from the direct aftermath of war towards more peaceful scenes of American life. He painted charming depictions of rural children at play, such as the iconic Snap the Whip (1872), and scenes of country schools like The Country School (1871). He also explored themes of leisure and tourism, painting elegant women strolling at Long Branch, New Jersey, or enjoying the mountain air. These works often possess a bright, sunlit quality and a sense of idyllic Americana, though sometimes tinged with a subtle melancholy or awareness of social change.

Mastery of Watercolor

While Homer had experimented with watercolor earlier, influenced by his mother, the 1870s marked his emergence as a major force in the medium. He embraced watercolor with increasing passion and technical brilliance, finding it perfectly suited to his desire for directness, spontaneity, and capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. He traveled frequently during this decade, seeking fresh subjects. He made several trips to the Adirondack Mountains in upstate New York, painting guides, hunters, fishermen, and the rugged wilderness with remarkable freshness and vitality.

He also spent time in Gloucester, Massachusetts, a bustling fishing port. Here, he began to explore themes related to the sea and the lives of those who depended on it, painting dory fishermen and harbor scenes. His watercolors from this period are characterized by their fluid washes, bold compositions, and luminous transparency. He quickly gained recognition as a leading American watercolorist, helping to elevate the medium from a sketching tool or amateur pastime to a major form of artistic expression.

A pivotal experience came in 1881-1882 when Homer spent nearly two years in Cullercoats, a fishing village on the North Sea coast of England, near Tynemouth. Immersed in this community, he focused intently on the lives of the fisherfolk, particularly the sturdy, heroic women who waited anxiously for their men to return from the perilous sea. The dramatic coastal weather and the stoic resilience of the inhabitants provided powerful inspiration. His Cullercoats works, in both watercolor and oil, are often more somber and monumental than his earlier pieces, reflecting a deeper engagement with themes of human struggle against the forces of nature. This period marked a significant maturation in his art, setting the stage for his final, most powerful phase.

The Sage of Prout's Neck

In 1883, seeking greater solitude and a closer connection to the elemental forces he increasingly wished to depict, Homer made a decisive move. He relocated permanently to Prout's Neck, a remote, rocky peninsula on the coast of Maine. His father and brother had already established summer homes there, but Winslow sought year-round immersion. He had a studio built, strategically positioned to offer dramatic views of the Atlantic Ocean. Here, largely isolated from the art world's social demands, he would spend the rest of his life, dedicating himself to observing and painting the sea in all its moods.

Prout's Neck became Homer's ultimate subject. He painted the crashing surf, the rugged coastline, the changing weather, and the relationship between humanity and the powerful, indifferent ocean. His works from this period are considered the pinnacle of his achievement. Paintings like The Life Line (1884), depicting a dramatic sea rescue, showcase his narrative skill and technical prowess. The Fog Warning (1885) captures the quiet anxiety of a lone fisherman realizing he may not make it back to his mother ship before fog engulfs him.

Other major oils from this era include Eight Bells (1886), showing sailors navigating by sextant on a stormy deck, and Northeaster (1895, reworked 1901), a pure marine painting focusing on the raw power of waves crashing against rocks. In these mature works, Homer achieved a profound synthesis of realism and expressive force. While meticulously observed, his seascapes transcend mere description to evoke universal themes of struggle, survival, solitude, and the sublime power of nature. He became known as the "Sage of Prout's Neck," a somewhat reclusive figure dedicated entirely to his art.

The Gulf Stream and Later Years

One of Homer's most famous and enigmatic paintings, The Gulf Stream, was completed in 1899 (with later modifications). It depicts a lone Black sailor adrift on a dismasted, rudderless boat in shark-infested waters, with a waterspout looming ominously on the horizon. The painting is a harrowing image of isolation and impending doom. Its meaning has been widely debated: is it a commentary on the precarious situation of African Americans in the post-Reconstruction era, a reflection on the legacy of slavery, a universal allegory of human struggle against fate, or a combination of these? Homer himself remained characteristically tight-lipped about its specific meaning, allowing its ambiguity to enhance its power.

Despite his relative isolation in Maine, Homer continued to travel periodically, seeking new subjects and warmer climes, particularly during the harsh winters. He made several trips to Florida, the Bahamas, and Bermuda in the 1880s, 1890s, and early 1900s. These trips resulted in a stunning series of watercolors, characterized by brilliant light, vibrant color, and dazzling technical facility. He captured the tropical landscapes, marine life, and local inhabitants with extraordinary immediacy and freshness. These late watercolors are among the most celebrated works in the medium, demonstrating his undiminished skill and visual curiosity.

Homer achieved significant recognition during his later years. He exhibited regularly, won awards (including a gold medal at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900), and his works were acquired by major museums and collectors. He was elected a full member of the National Academy of Design in 1865. His participation in events like the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where he exhibited fifteen paintings, solidified his reputation both nationally and internationally. Though perhaps not enjoying the same level of popular fame as some European contemporaries during his lifetime, he was highly respected within the art world.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Winslow Homer's style evolved significantly throughout his career, yet it remained consistently grounded in direct observation and a commitment to realism. He was largely self-taught, which allowed him to develop a highly personal and independent artistic vision, less constrained by academic conventions than many of his peers. His early work as an illustrator instilled a strong sense of graphic design and narrative clarity.

His transition to oil painting revealed his talent for solid composition and capturing the weight and volume of forms. His Civil War paintings and early genre scenes demonstrate a straightforward, objective approach, though often imbued with subtle psychological depth. Exposure to European art, particularly French painting, seems to have encouraged a greater interest in light effects and perhaps a slightly looser brushstroke, though he never fully embraced Impressionism's dissolution of form.

Homer's mastery of watercolor was exceptional. He exploited the medium's transparency and fluidity to create works of remarkable luminosity and spontaneity. His techniques ranged from broad, wet washes to precise, dry-brush details, often combined within a single work. He was adept at using the white of the paper to represent highlights, giving his watercolors a sparkling brilliance.

In his mature Prout's Neck seascapes, Homer achieved a powerful synthesis of detailed realism and expressive force. He meticulously studied wave dynamics and coastal geology, yet his paintings convey the raw, elemental energy of the ocean. His compositions are often bold and dramatic, emphasizing the confrontation between land and sea, or humanity and nature. While fundamentally a realist, his later works can carry symbolic weight, exploring themes of mortality, struggle, and the sublime. Compared to his contemporary Thomas Eakins, another great American realist focused on anatomical accuracy and scientific observation, Homer's realism often feels more intuitive, atmospheric, and emotionally resonant.

Personal Life and Character

Winslow Homer was known for being intensely private, even reclusive, especially in his later years at Prout's Neck. He never married and appears to have had few, if any, deep romantic attachments. Anecdotes about a possible unrequited love or a "mystery woman" remain speculative and unsubstantiated, fitting the enigmatic aura he cultivated. He valued his independence and solitude, finding them essential for his artistic concentration.

He was a practical, down-to-earth man, deeply connected to the outdoors. He enjoyed fishing and hunting, and his direct experiences in nature informed his art. His self-reliance and stoicism are often seen as mirroring the qualities he admired and depicted in his subjects – the soldiers, farmers, guides, and fisherfolk who faced hardship with quiet resilience. While reserved, he was not unfriendly, maintaining correspondence with family, dealers, and fellow artists, though he generally avoided the social whirl of the art world. His dedication to his craft was absolute, defining his life and legacy.

Influence and Legacy

Winslow Homer's impact on American art is immense and enduring. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest American painters of the 19th century, a key figure in the development of a distinctly American artistic voice. His commitment to depicting American subjects with honesty and insight helped steer American art away from European dominance towards a greater engagement with its own landscape and experience.

He significantly elevated the status of watercolor painting in America, demonstrating its potential for major artistic statements. His technical innovations and expressive power in the medium inspired generations of subsequent watercolorists. His realistic yet evocative style influenced many later artists. The painters of the Ashcan School, such as Robert Henri, George Bellows, John Sloan, and George Luks, admired his directness and focus on contemporary American life, even as their own subject matter shifted to the urban environment.

Later American realists like Edward Hopper and Andrew Wyeth can be seen as heirs to Homer's tradition of careful observation combined with psychological depth and a strong sense of place. Hopper, in particular, shared Homer's interest in solitude and the evocative power of light. Homer's influence extends beyond specific stylistic imitation; his independence, integrity, and profound connection to the American landscape continue to resonate.

While distinct in style from contemporaries like the expatriate cosmopolitans James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent, or the visionary sea painter Albert Pinkham Ryder, Homer holds a unique and central place. He engaged directly with American themes – from the Civil War and Reconstruction to the relationship between humanity and the wilderness – in a way few others did, creating images that have become icons of American culture. His work stands alongside that of other chroniclers of American life, like the western scenes of Frederic Remington or the Impressionist views of Mary Cassatt, as vital parts of the nation's artistic heritage.

Homer in Museums

Today, Winslow Homer's works are prized possessions of major art museums across the United States and beyond. The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York holds a significant collection, including iconic oils like The Gulf Stream and Prisoners from the Front, as well as numerous watercolors. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., also boasts a superb collection, featuring masterpieces like Breezing Up (A Fair Wind) and key Cullercoats paintings.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, located in his city of birth, has extensive holdings reflecting his entire career. The Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts, offers a remarkably comprehensive collection, including oils, watercolors, drawings, and a vast array of his early illustrations and prints. The Philadelphia Museum of Art is home to The Life Line. Other institutions with important Homer collections include the Art Institute of Chicago, the Addison Gallery of American Art, the Portland Museum of Art in Maine (near Prout's Neck), the Worcester Art Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and university museums like the Georgia Museum of Art (noted for its collection of Homer's wood engravings). These collections allow audiences to trace Homer's artistic development and appreciate the breadth and depth of his achievement.

Conclusion

Winslow Homer carved a unique path through American art, evolving from a skilled illustrator to a painter of profound depth and power. His work captured the essence of 19th-century America – its conflicts, its landscapes, its people – with an unflinching eye and remarkable technical skill. Whether depicting the sun-drenched play of children, the grim realities of war, the rugged beauty of the wilderness, or the awesome power of the sea, Homer brought a sense of authenticity and gravitas to his subjects. His mastery of both oil and watercolor, his independent spirit, and his deep connection to the natural world cemented his legacy as a foundational figure in American art, an artist whose vision continues to speak with clarity and force today.