Angelo Morbelli stands as a pivotal figure in late 19th and early 20th-century Italian art, a master whose canvases captured not only the changing landscapes of his nation but also the profound social currents shaping its society. Born in Alessandria on July 18, 1853, and passing away in Milan on November 7, 1919, Morbelli was a leading proponent of Italian Divisionism, a movement that sought to render light and atmosphere through a scientific application of color. His life and work offer a compelling window into an era of artistic innovation and social consciousness.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Morbelli's journey into the world of art was not a direct path. Initially, he harbored aspirations in music. However, a progressive hearing impairment, which eventually led to significant deafness, compelled him to seek an alternative mode of expression. This challenge, rather than hindering him, steered him towards the visual arts, a realm where he would leave an indelible mark. In 1867, his burgeoning talent was recognized with a local study scholarship, enabling him to move to Milan, the vibrant artistic hub of northern Italy.

He enrolled at the prestigious Accademia di Brera, a cornerstone of artistic education in Italy. From 1867 until 1876, Morbelli honed his skills under the tutelage of respected academicians such as Raffaele Casini and Giuseppe Bertini. Bertini, in particular, was known for his historical and allegorical paintings, and his influence, along with the prevailing academic traditions, shaped Morbelli's early output. During this formative period, Morbelli excelled in perspective drawing and created works that aligned with the academic tastes of the time, often featuring allegorical subjects and historical scenes. An example from this phase is his 1880 painting, Goethe Dying, a work characterized by its dramatic composition and refined, albeit traditional, use of color. These early pieces demonstrated a meticulous technique and a keen eye for detail, laying the groundwork for his later, more innovative explorations.

The Turn Towards Social Realism

The 1880s marked a significant thematic shift in Morbelli's art. While his academic training provided a strong technical foundation, he began to look beyond historical and mythological subjects, turning his gaze towards the contemporary realities of Italian society. He became increasingly preoccupied with themes of labor, poverty, and the plight of the marginalized. This was a period of great social upheaval in Italy, with industrialization creating new social classes and exacerbating existing inequalities. Artists across Europe, including Gustave Courbet in France and later the Ashcan School in America, were similarly engaging with social realism.

Morbelli's engagement with these themes was profound and empathetic. He sought to portray the dignity and suffering of ordinary people, particularly the elderly and the working class. One of his most notable early works in this vein is Giorni ultimi! (The Last Days!), completed in 1883. This poignant painting depicts elderly men seated on a bench within the Pio Albergo Trivulzio, a large charitable institution in Milan that provided shelter for the aged poor. The work captures a sense of quiet despair and resignation, rendered with a sensitivity that would become a hallmark of Morbelli's social commentary. The Pio Albergo Trivulzio would become a recurring setting in his oeuvre, allowing him to explore themes of old age, solitude, and institutional life with depth and compassion.

Embracing Divisionism: The Science of Light

Parallel to his thematic evolution, Morbelli was at the forefront of a technical revolution in Italian painting: Divisionism. Emerging in the late 1880s and flourishing in the 1890s, Italian Divisionism, known as Divisionismo, shared theoretical underpinnings with French Neo-Impressionism, pioneered by Georges Seurat and Paul Signac. Both movements were based on optical science and color theory, particularly the ideas of Michel Eugène Chevreul and Ogden Rood. Instead of mixing pigments on the palette, Divisionist painters applied small, distinct dots or strokes of pure color directly onto the canvas, intending for them to blend optically in the viewer's eye. This technique aimed to achieve greater luminosity and vibrancy than traditional methods.

Morbelli, alongside artists like Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, and Plinio Nomellini, became a leading figure in this movement. Vittorio Grubicy de Dragon, an art critic and dealer, was instrumental in promoting Divisionism and its artists. For Morbelli, the Divisionist technique was not merely a stylistic choice; it was a means to enhance the expressive power of his subjects. He meticulously studied the properties of light and color, even experimenting with the chemical composition of his pigments to achieve the desired effects. His adoption of Divisionism around 1888-1890 allowed him to imbue his scenes, whether sun-drenched landscapes or dimly lit interiors, with an unprecedented radiance and atmospheric depth.

The social implications of Divisionism were also significant for Morbelli and his contemporaries. Many Divisionists, including Morbelli and Pellizza da Volpedo, held socialist or humanitarian sympathies. They saw the technique's emphasis on light and clarity as a metaphor for enlightenment and social progress. Art, for them, could be a vehicle for social reform and human redemption, a way to illuminate the conditions of modern life and inspire change.

Masterworks of Divisionism and Social Concern

Morbelli's mature period saw the creation of some of his most celebrated works, where his Divisionist technique and social concerns converged powerfully.

Per Ottanta Centesimi! (For Eighty Cents!)

Painted in 1895, For Eighty Cents! is arguably one of Morbelli's most iconic and socially charged works. It depicts a group of women, known as mondine (rice-weeders), toiling in the flooded rice paddies of the Po Valley. The title refers to their meager daily wage. The painting is a stark portrayal of grueling agricultural labor, with the bent figures of the women silhouetted against the shimmering, water-logged landscape. Morbelli's Divisionist technique masterfully captures the reflections on the water and the humid atmosphere, while simultaneously highlighting the arduous nature of the work. The painting was exhibited at the Venice Biennale and became a powerful symbol of the exploitation of rural laborers. It resonates with the social realist concerns of artists like Jean-François Millet, whose depictions of peasant life in France had a profound impact on subsequent generations.

The Pio Albergo Trivulzio Series

Morbelli returned repeatedly to the subject of the Pio Albergo Trivulzio. Works like Un Natale al Pio Albergo Trivulzio (A Christmas at the Pio Albergo Trivulzio) and Il Viatico (The Viaticum, or Last Rites) explore the lives of its elderly residents with profound empathy. His Divisionist brushwork, often employing long, filament-like strokes, created a unique texture that conveyed the somber, reflective mood of these interiors. The play of light, often filtering through windows or emanating from a distant source, added a spiritual dimension to these scenes of quiet suffering and contemplation. These works stand as a testament to his sustained engagement with the themes of aging, charity, and mortality.

Landscapes and Light

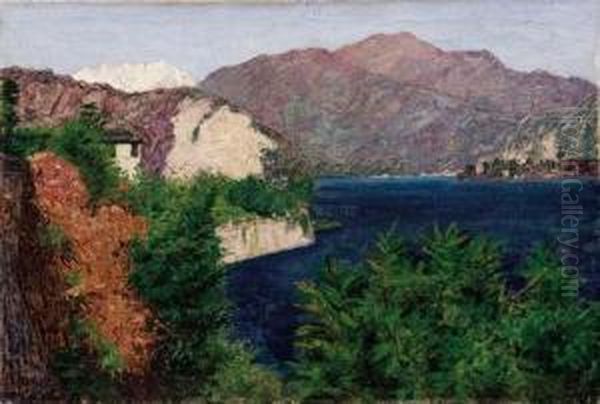

While renowned for his social themes, Morbelli was also a gifted landscape painter. He applied his Divisionist technique to capture the varied scenery of Italy, from the alpine vistas to tranquil lakesides. Works such as Tramonto in montagna (Sunset in the Mountains, 1907) and Lago Maggiore showcase his ability to render the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere with dazzling precision. In these paintings, the landscape itself becomes a subject of profound beauty and emotional resonance, with the fragmented brushstrokes coalescing into vibrant tapestries of color. His approach to landscape can be compared to that of his contemporary Segantini, who also used Divisionism to depict the grandeur of the Alps, though often with a more overt symbolism.

Other notable works that demonstrate his versatility include Veduta del porto di Savona (View of the Port of Savona), which captures the bustling activity and light of a coastal scene, and various depictions of sunsets and seasonal changes, all rendered with his characteristic luminous touch.

Relationships with Contemporaries and Artistic Circles

Angelo Morbelli was an active participant in the artistic debates and communities of his time. His relationship with fellow Divisionists was complex, characterized by shared artistic goals, mutual respect, and, at times, professional rivalry.

Giovanni Segantini was perhaps the most internationally renowned of the Italian Divisionists. While both artists were committed to the Divisionist technique, their thematic concerns and artistic temperaments differed. Segantini's work often veered towards symbolism and a pantheistic vision of nature, particularly in his majestic Alpine scenes. Morbelli, while also a master of landscape, remained more grounded in social realism and the depiction of everyday life. Despite these differences, they were key figures in establishing Divisionism as a significant force in Italian art.

Gaetano Previati was another prominent Divisionist, known for his more lyrical and often symbolic compositions. His brushwork could be more fluid and elongated than Morbelli's, creating a distinctive, almost ethereal quality. Previati, Morbelli, and Segantini are often considered the triumvirate at the core of the movement.

Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo was a close associate and a fellow advocate for social themes within Divisionism. His most famous work, Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate), is a monumental depiction of a workers' procession and a landmark of social realist art. Morbelli and Pellizza collaborated on organizing exhibitions, such as their efforts for the Turin Triennale in 1896, where they aimed to present a unified front for Divisionist art, though they faced challenges and resistance from more conservative elements of the art establishment and even from within their ranks, as Segantini's absence due to other commitments impacted the show. Artists like a certain Carpi and Cairati were noted as being in opposition during these efforts.

Vittorio Grubicy de Dragon, as mentioned, played a crucial role as a critic, dealer, and theorist, championing the Divisionist cause and helping to articulate its principles. Other artists associated with or influenced by Divisionism include Emilio Longoni, who also focused on social themes, and Plinio Nomellini, whose work often had a more idyllic or symbolic character. The innovations of Divisionism would later have a significant impact on the next generation of Italian artists, particularly the Futurists, such as Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, and Carlo Carrà, who adapted its principles of fragmented color and dynamic light to express speed, technology, and the modern urban experience.

Morbelli also engaged with figures beyond the immediate circle of painters. His collaboration with the entrepreneur and furniture designer Eugenio Quarti is noteworthy. Morbelli's artistic connections helped bring new clientele to Quarti, enhancing the designer's reputation and expanding his business, illustrating the interconnectedness of art and commerce during this period.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and Later Years

Morbelli's talent and innovative approach garnered significant recognition during his lifetime. He exhibited his work regularly in Italy and internationally. His participation in the Venice Biennale, a prestigious international art exhibition, was a recurring feature of his career; for instance, he exhibited in the 1903 edition with a series of works depicting life in the Pio Albergo Trivulzio.

A major early success was winning a gold medal at the Paris Universal Exposition of 1889, an event that brought international acclaim to many artists, including those working in new styles like Impressionism and Neo-Impressionism. This award helped to solidify his reputation outside of Italy. He also exhibited in Milan, Rome, and Turin, contributing to the growing visibility and acceptance of Divisionism.

In his later years, Morbelli continued to paint with undiminished dedication. He established his studio and residence at Villa Maria, located in the Colma di Rosignano Monferrato, a place that remained in his family and, much later, was opened to the public by his descendants. He spent his final years primarily in Milan, the city that had been central to his artistic development and career.

His work continued to be exhibited even posthumously. For example, in 2008, his paintings were featured in the significant exhibition "Radical Light: Italy's Divisionist Painters 1891-1910," held at the National Gallery in London and the Kunsthalle Zürich. This exhibition brought renewed international attention to Italian Divisionism and Morbelli's role within it. His works are held in numerous public and private collections, including the Galleria d'Arte Moderna in Milan, the Fondazione Cariplo, and various other Italian museums. Publications such as Massima Luce: Controversie: Divisionisti ed Accademici have documented the movement and its key figures, including Morbelli.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Angelo Morbelli is remembered as one of an elite group of six principal figures of Italian Divisionism and one of its most rigorous and intellectually engaged practitioners. His commitment to the scientific principles of color and light was matched by his profound humanism. He was not content merely to create aesthetically pleasing images; his art was a vehicle for social commentary and a testament to the lives of those often overlooked by society.

Art historians regard Morbelli as a master of capturing atmosphere and emotion through his meticulous Divisionist technique. His depictions of the elderly in the Pio Albergo Trivulzio are particularly praised for their sensitivity and psychological depth. He managed to convey both the somber reality of their existence and an inherent dignity. Similarly, his paintings of laborers, like For Eighty Cents!, are powerful indictments of social injustice, rendered with a technical brilliance that amplifies their impact.

His contribution to landscape painting is also significant. He brought the same analytical rigor and sensitivity to his depictions of nature, creating works that shimmer with light and color. His influence extended to the subsequent Futurist movement, which built upon the Divisionists' experiments with fragmented form and dynamic sensation.

Angelo Morbelli's legacy is that of an artist who successfully bridged the gap between technical innovation and social conscience. He was a pioneer who helped to shape the course of modern Italian art, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with its beauty, its technical mastery, and its compassionate portrayal of the human condition. His dedication to his craft, even in the face of personal challenges like his deafness, and his unwavering focus on themes of social importance, secure his place as a distinguished and enduring figure in the annals of art history. His Villa Maria, maintained by his descendants like Roberto Morbelli, who organized an exhibition at the Museo Casale Insieme in Casale Monferrato in 2019, stands as a living testament to his life and work.