Giuseppe Pellizza, who later appended "da Volpedo" to his name to honor his birthplace, stands as a pivotal figure in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Italian art. Born on July 28, 1868, in Volpedo, a small agricultural town in the Piedmont region of Italy, and tragically ending his own life on June 14, 1907, Pellizza's relatively short career was marked by intense artistic exploration, a profound social conscience, and the creation of one of Italian art's most iconic images, Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate). He was a leading proponent of Italian Divisionism, a movement that, while drawing inspiration from French Neo-Impressionism, developed its own unique characteristics and thematic concerns, deeply rooted in the Italian social and cultural landscape.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Giuseppe Pellizza was born into a family of modest, landowning farmers, Pietro and Maddalena Cantù. His rural upbringing in Volpedo would remain a constant source of inspiration throughout his life, with the landscapes and people of his native region frequently appearing in his work. Recognizing his precocious talent for drawing, his family supported his artistic inclinations. This support enabled him to pursue formal artistic training, a crucial step in honing his innate abilities.

His academic journey began at the prestigious Brera Academy of Fine Arts in Milan, a major center for artistic education in Italy. Here, he would have been exposed to the prevailing academic traditions, but also to the burgeoning modernist currents that were beginning to challenge established norms. Among his teachers at the Brera was Francesco Hayez, a leading figure of Italian Romanticism, though Hayez's direct influence on Pellizza's mature style would be less significant than later encounters.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Pellizza continued his studies in Rome, first at the Accademia di San Luca and then as a student of the Accademia di Spagna, which provided opportunities for Italian artists to study in the historic capital. He later moved to Florence, enrolling at the Accademia di Belle Arti. In Florence, he studied under Giovanni Fattori, one of the leading figures of the Macchiaioli movement. The Macchiaioli, with their emphasis on capturing the effects of light and shadow through "macchie" (patches or spots of color) and their commitment to depicting everyday life and contemporary historical events, likely had a formative influence on Pellizza's developing interest in realism and the optical qualities of light.

His peripatetic education also included periods at the Accademia Ligustica di Belle Arti in Genoa and a significant stay in Bergamo, where he attended the Accademia Carrara under Cesare Tallone, a painter known for his portraiture and genre scenes. These varied educational experiences exposed Pellizza to a range of artistic approaches and philosophies, equipping him with a solid technical foundation while also fueling his desire to find his own unique artistic voice. He also undertook study trips, including one to Paris for the Universal Exposition of 1889, where he would have encountered firsthand the works of French Impressionists and Neo-Impressionists, an experience that would prove crucial for his later adoption of Divisionist techniques.

The Emergence of Divisionism and Pellizza's Path

The late 19th century was a period of significant artistic innovation across Europe. In France, Georges Seurat and Paul Signac were pioneering Neo-Impressionism, also known as Pointillism, a technique based on scientific theories of optics and color. They advocated for the application of small, distinct dots of pure color to the canvas, intending for these colors to mix optically in the viewer's eye, thereby achieving greater luminosity and vibrancy than could be obtained through traditional color mixing on the palette.

This new approach to color and light found fertile ground in Italy, where it evolved into Divisionism (Divisionismo). While sharing the Neo-Impressionist interest in optical color mixing, Italian Divisionism often featured more elongated, filament-like brushstrokes rather than just dots, and frequently tackled themes of social realism, symbolism, and landscape with a particular emotional intensity. Key figures in the development of Italian Divisionism included Giovanni Segantini, known for his luminous Alpine landscapes and symbolic peasant scenes; Angelo Morbelli, who often depicted the elderly and marginalized with poignant sensitivity; and Gaetano Previati, whose work leaned towards Symbolism with flowing lines and mystical themes. Vittore Grubicy de Dragon, an art critic and gallerist as well as a painter, played a crucial role in promoting Divisionism and articulating its theoretical underpinnings in Italy.

Pellizza da Volpedo was drawn to these new artistic currents. He began experimenting with Divisionist techniques around 1891, meticulously studying color theory and its application. His commitment to this method was not merely technical; he saw it as a means to achieve a heightened sense of reality and to imbue his subjects with greater clarity and expressive power. He engaged in correspondence with fellow artists and assiduously read scientific treatises on optics and color, seeking to master the principles that underpinned the Divisionist approach.

Social Conscience and Thematic Focus

Pellizza's art became increasingly infused with a deep social consciousness, reflecting the turbulent socio-political climate of late 19th-century Italy. The country was grappling with industrialization, widespread poverty, labor unrest, and growing socialist movements. Pellizza, with his roots in a rural community and his empathetic nature, was profoundly moved by the struggles of the working class and agricultural laborers.

His paintings began to address themes of social justice, labor, and the dignity of the common person. He sought to create an art that was not only aesthetically innovative but also socially relevant, capable of communicating powerful messages about the human condition. This commitment to social themes aligned him with a broader European trend of Social Realism, seen in the works of artists like Jean-François Millet in France, whose depictions of peasant life resonated with many artists concerned with social issues.

Pellizza’s early explorations in this vein include Ambasciatori della fame (Ambassadors of Hunger), completed in 1892. This work, depicting a group of striking workers, already shows his move towards monumental compositions and his desire to give voice to the dispossessed. The figures are rendered with a stark realism, their expressions conveying a sense of grim determination. While not yet fully Divisionist in technique, it foreshadows the direction his art would take.

Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate): An Icon of an Era

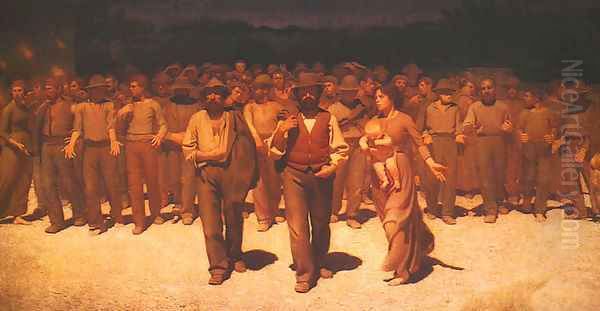

Pellizza da Volpedo's most famous and arguably most important work is Il Quarto Stato (The Fourth Estate). He labored on this monumental canvas for nearly a decade, beginning preliminary studies around 1891 and completing the final version in 1901. The painting is a powerful and iconic depiction of a procession of striking workers, advancing purposefully towards the viewer.

The title itself, "The Fourth Estate," refers to the working class as a new social and political force, distinct from the traditional three estates (clergy, nobility, and bourgeoisie). The painting was originally conceived under different titles, including Ambasciatori della Fame (a more developed version of his earlier work) and later Fiumana (The Human Flood or The River of Humanity), indicating the evolving conceptualization of the work. The final title firmly places it within the context of socialist thought and the rising awareness of proletarian power.

The composition is masterful. A determined group of men, women, and children stride forward from a shadowed background into a brightly lit foreground. The figures in the front row are particularly individualized: a strong, resolute man in the center, flanked by another man and a woman holding a child. Their expressions are serious yet hopeful, conveying both the hardship of their lives and their collective strength and aspiration for a better future. Pellizza used local peasants and workers from Volpedo as models, lending an air of authenticity and immediacy to the scene.

Technically, Il Quarto Stato is a triumph of Divisionism. Pellizza meticulously applied small strokes and dots of complementary colors, creating a vibrant, luminous surface that seems to shimmer with light. The technique enhances the sense of movement and the solidity of the figures, giving them an almost sculptural presence. The careful orchestration of color and light contributes to the painting's overall impact, making the advancing crowd appear both real and symbolic.

The creation of Il Quarto Stato was an arduous process. Pellizza made numerous preparatory drawings and oil studies, experimenting with composition and color. He documented his progress and his artistic intentions in his diaries and letters, revealing the depth of his commitment to the project. He wrote of his desire to create a work that would be "eloquent, strong, and healthy," a testament to the struggles and hopes of the working class.

Upon its first public exhibition at the Quadriennale in Turin in 1902, Il Quarto Stato did not immediately achieve the widespread acclaim Pellizza might have hoped for. Its overtly political subject matter and monumental scale were perhaps challenging for contemporary audiences. However, its significance grew over time. It was purchased by public subscription for the city of Milan in 1920 and eventually found its home in the Galleria d'Arte Moderna, Milan, before being moved to the Museo del Novecento, where it remains a central attraction. The painting has become an enduring symbol of workers' rights and social protest, not only in Italy but internationally, its imagery frequently reproduced and referenced in various contexts.

Other Notable Works and Artistic Development

While Il Quarto Stato is his magnum opus, Pellizza created many other significant works that showcase his artistic range and thematic concerns. Lo specchio della vita (E ciò che l'una fa, l'altre fanno) (The Mirror of Life (And what one does, the others do)), completed between 1895 and 1898, is a large-scale Divisionist painting depicting a flock of sheep moving along a sun-dappled path. This work, while seemingly a pastoral scene, carries symbolic overtones about conformity, the cycle of life, and perhaps the collective unconscious. The meticulous application of Divisionist brushstrokes creates a dazzling effect of light filtering through the leaves and reflecting off the animals' fleece.

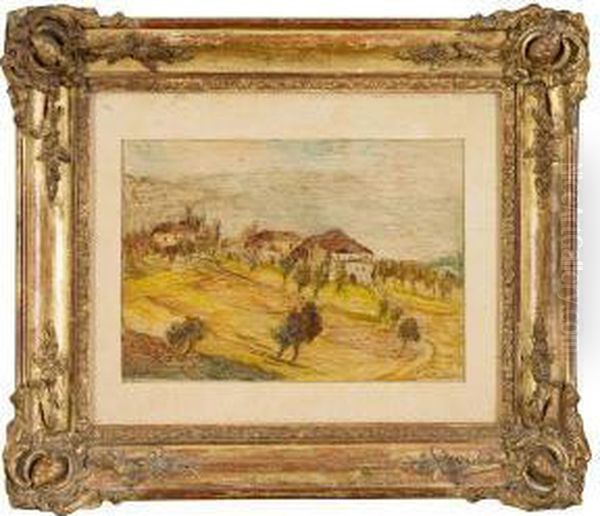

His landscapes, often depicting the countryside around Volpedo, are imbued with a lyrical quality and a profound sensitivity to the changing effects of light and atmosphere. Works like Paesaggio (Volpedo) (Landscape (Volpedo)) from 1897 or Mattino di maggio o Alberi e nubi (May Morning or Trees and Clouds) from 1903 demonstrate his mastery of Divisionist technique in capturing the nuances of nature. These paintings are not mere topographical records but are infused with a sense of pantheistic wonder and a deep connection to his native land.

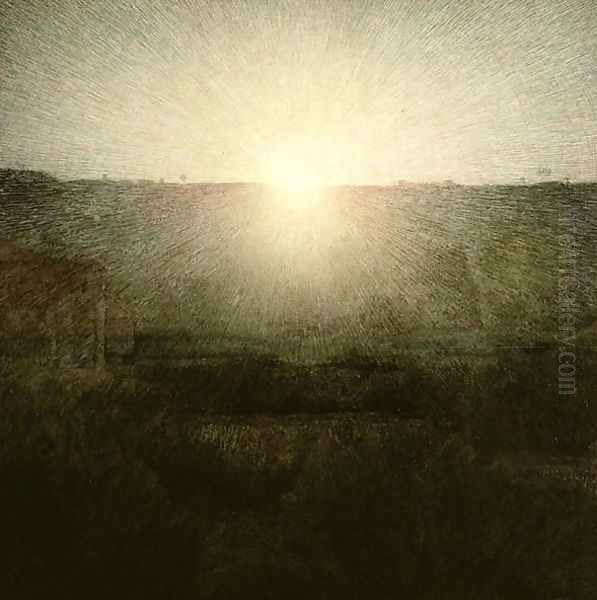

Pellizza also produced sensitive portraits, such as Ritratto di Signora Sophia Abbiati. His dedication to the Divisionist method extended to these works, where the play of light on skin and fabric was rendered through the careful juxtaposition of color. He also explored allegorical and symbolic themes in works like Il Sole Nascente (The Rising Sun), a radiant depiction of the sun that can be interpreted as a symbol of hope and renewal, themes that resonated with the progressive and socialist ideals of the era.

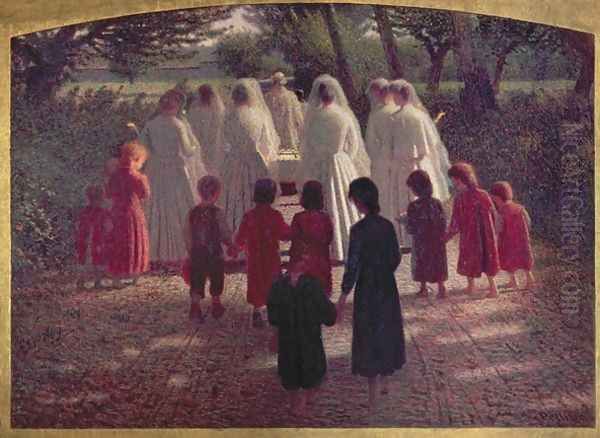

Throughout the 1890s and into the early 1900s, Pellizza continued to refine his Divisionist technique. He was part of a vibrant artistic community, corresponding and exhibiting with fellow Divisionists like Giovanni Segantini, Angelo Morbelli, Emilio Longoni, Plinio Nomellini, and Gaetano Previati. These artists, while sharing a common technical approach, each developed individual styles and thematic preoccupations. Segantini, for instance, focused on the majestic landscapes of the Alps and the lives of its inhabitants, often imbuing his scenes with a mystical symbolism. Morbelli, in works like Il Natale dei rimasti (Christmas of Those Left Behind), explored themes of old age and social isolation with a quiet pathos. Longoni often depicted urban workers and scenes of social unrest. Previati, on the other hand, moved towards a more overtly Symbolist and even Art Nouveau-inflected style in works like Maternità (Motherhood). Pellizza's work stands out within this group for its unique blend of monumental social realism and lyrical naturalism, all rendered with a rigorous yet expressive Divisionist technique.

Personal Tragedies and Premature Death

Despite his artistic achievements and growing recognition, Pellizza's personal life was marked by profound sorrow. He was deeply devoted to his wife, Teresa Bidone, whom he married in 1892, and their children. However, tragedy struck when Teresa died in 1905 after giving birth to their third child. This loss devastated Pellizza. Compounded by the earlier death of their firstborn son, Pietro, and the pressures of his artistic career, which, despite his dedication, did not always bring financial stability or immediate critical success, Pellizza fell into a deep depression.

The weight of these personal tragedies became unbearable. On June 14, 1907, at the age of just 38, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo took his own life in his studio in Volpedo, the very place where he had created so many powerful and enduring works of art. His suicide was a tragic end to a life of intense artistic striving and profound human empathy.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo's legacy is multifaceted. He is recognized as one of the foremost exponents of Italian Divisionism, a movement that made a distinctive contribution to European modernism. His rigorous application of color theory and his innovative brushwork resulted in paintings of extraordinary luminosity and visual power. He successfully adapted the scientific principles of Neo-Impressionism to address themes that were deeply rooted in the Italian experience.

His masterpiece, Il Quarto Stato, has transcended its art historical context to become a universal symbol of social justice and the collective struggle for human dignity. Its influence can be seen in subsequent artistic movements and its imagery continues to resonate in contemporary culture. The painting stands as a testament to Pellizza's belief in the power of art to effect social change and to give voice to the aspirations of the common people.

Beyond Il Quarto Stato, Pellizza's broader oeuvre, including his landscapes and symbolic works, reveals a sensitive and poetic artist deeply attuned to the beauty of nature and the complexities of the human condition. His dedication to his craft, his intellectual engagement with artistic theory, and his profound empathy for his subjects mark him as a significant figure in the history of art.

His work provided a crucial link between the 19th-century realist traditions, such as those of the Macchiaioli (represented by his teacher Giovanni Fattori and others like Telemaco Signorini), and the emerging avant-garde movements of the early 20th century. While the Futurists, who burst onto the Italian art scene shortly after Pellizza's death with figures like Umberto Boccioni and Giacomo Balla (both of whom, incidentally, had early Divisionist phases), would champion dynamism and technology in a radically different way, Pellizza's commitment to modern technique and socially relevant subject matter helped pave the way for a new era in Italian art.

Today, Pellizza da Volpedo's paintings are housed in major museums in Italy and abroad, and his life and work continue to be the subject of scholarly research and public admiration. His studio in Volpedo has been preserved as a museum, offering visitors a glimpse into the world of this remarkable artist. Through his art, Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo remains a luminous force, illuminating both the social struggles of his time and the enduring power of the human spirit.