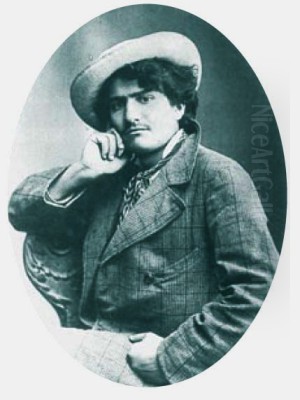

Giovanni Segantini stands as a monumental figure in late 19th-century European art, an artist whose life was as dramatic and rugged as the Alpine landscapes he so masterfully depicted. Born into hardship and dying prematurely at the height of his powers, Segantini forged a unique artistic path, blending meticulous observation of nature with profound symbolic meaning. He became Italy's foremost Divisionist painter and a key exponent of international Symbolism, leaving behind a body of work celebrated for its luminous intensity, spiritual depth, and evocative portrayal of life in the high Alps.

A Childhood Forged in Hardship

Giovanni Battista Emmanuele Maria Segatini – he later changed the spelling – was born on January 15, 1858, in Arco, a town then part of the Austrian Empire's County of Tyrol (now in Trentino, Italy). His early life was marked by profound loss and instability. His mother, Margherita de Girardi, died when he was just seven years old. His father, Agostino Segatini, a struggling merchant, left Giovanni in the care of his older stepsister, Irene, and sought work elsewhere, only to die himself a year later. The young Giovanni found himself an orphan, adrift in a world that offered little comfort.

Irene moved with Giovanni to Milan, hoping for better prospects. However, life remained difficult. Giovanni, feeling neglected and restless, ran away. He was later found living on the streets and briefly confined to a reformatory, the Riformatorio Marchiondi. It was within this institution, ironically, that his artistic talent first received recognition. A chaplain noticed his drawings and encouraged him, arranging for some rudimentary instruction. This early experience, though harsh, perhaps instilled in him a resilience and a deep connection to the struggles of existence that would later inform his art.

Milan and the Brera Academy: Finding a Path

Upon his release, Segantini found work as an assistant to a photographer and later decorated signs and banners. Crucially, he managed to enroll in evening classes at the prestigious Brera Academy of Fine Arts (Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera) in Milan around 1875. Here, he studied ornamental art and later figure painting. Though his formal education was somewhat fragmented, the academy environment exposed him to artistic currents and fellow students who would shape his early career.

During his time at Brera, Segantini encountered the lingering influence of Romanticism, exemplified by figures like Francesco Hayez, but also the newer trends of Lombard Naturalism and the anti-academic sentiments of the Scapigliatura movement. He formed friendships with other aspiring artists, including Emilio Longoni and Carlo Bugatti. Bugatti, who would become a renowned furniture designer, introduced Segantini to his sister, Bice Bugatti, who became Giovanni's lifelong companion and the mother of his four children. This connection to the Bugatti family provided crucial personal and artistic support throughout his life.

Segantini's early works from this period, such as The Choir of Sant'Antonio (1879), show a mastery of traditional techniques and a leaning towards realism, capturing scenes of Milanese life with sensitivity. He quickly gained recognition, winning awards and attracting the attention of critics and dealers.

The Crucial Role of Vittore Grubicy

A pivotal moment in Segantini's career was his meeting with Vittore Grubicy de Dragon around 1879-1880. Grubicy, along with his brother Alberto, ran an important art gallery in Milan that promoted contemporary Italian artists. Vittore was more than just a dealer; he was a critic, an intellectual, and a fervent promoter of new artistic ideas, particularly French Impressionism and its developments. He saw immense potential in Segantini and became his mentor, advisor, and exclusive dealer for several years.

Grubicy encouraged Segantini to move away from the darker palette and urban subjects of his early work. He urged him to seek inspiration directly from nature and to explore the effects of light. This guidance was instrumental in Segantini's decision to leave Milan and immerse himself in rural life, a move that would fundamentally transform his art. Grubicy also introduced Segantini to the theoretical underpinnings of new color theories and the burgeoning Pointillist techniques emerging in France.

Brianza: Towards Light and Divisionism

Around 1881, seeking tranquility and a closer connection to nature, Segantini moved with Bice Bugatti to the Brianza region, a picturesque area of rolling hills and lakes north of Milan. This period marked a significant shift in his style. He began painting en plein air (outdoors), focusing on pastoral landscapes and scenes of peasant life. His palette brightened considerably, and his brushwork became more textured as he sought to capture the vibrant effects of natural light.

Works from the Brianza period, such as Ave Maria at Trasbordo (Ave Maria a trasbordo, c. 1882-86), show this transition. While still rooted in realism, they exhibit a heightened sensitivity to atmospheric conditions and light. He was deeply influenced by the realism of the French Barbizon School painter Jean-François Millet, whose depictions of peasant labor resonated with Segantini's own empathy for rural life. However, Segantini imbued his scenes with a lyrical quality and a growing sense of spiritual connection to the land.

It was during his time in Brianza, guided by Grubicy's insights and his own experiments, that Segantini began to develop his distinctive Divisionist technique. Unlike the small, uniform dots of French Pointillists like Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, Segantini employed elongated, thread-like brushstrokes of pure color. He applied these filaments side-by-side, intending for the viewer's eye to optically mix the colors, resulting in greater luminosity and vibrancy than could be achieved by mixing pigments on the palette. This technique allowed him to capture the intense, shimmering light of the Italian countryside.

Savognin: Embracing the Alpine Heights

In 1886, seeking even purer light and more dramatic landscapes, Segantini made a decisive move, relocating his family higher into the Alps, to Savognin in the Grisons canton of Switzerland. This marked the beginning of his mature phase, where his art would become inextricably linked with the high Alpine environment. The vast panoramas, the crystalline air, and the intense sunlight of the mountains provided the perfect subject matter for his evolving Divisionist style and his deepening spiritual concerns.

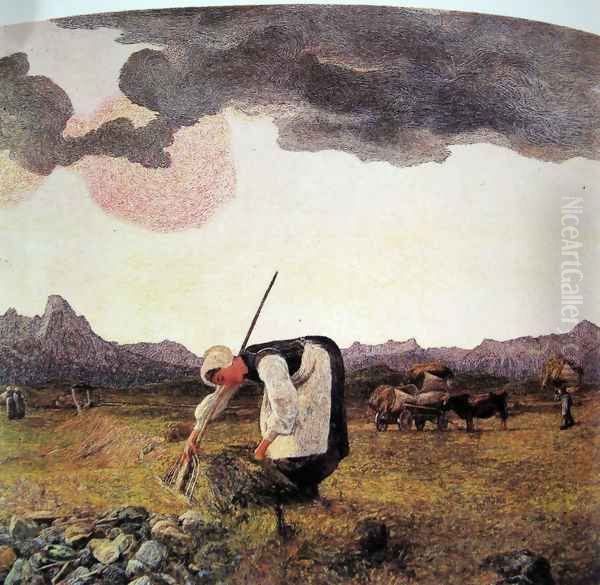

In Savognin, Segantini's technique reached its full expression. His brushstrokes became even more filament-like, weaving intricate tapestries of color that captured the dazzling light reflecting off snow and rock, the deep blues of the mountain shadows, and the changing moods of the Alpine weather. His subjects remained focused on rural life – shepherds with their flocks, women tending cattle, farmers working the high pastures – but these scenes took on an increasingly symbolic and monumental quality.

Paintings like Midday in the Alps (Mezzogiorno sulle Alpi, 1891) and Ploughing (Aratura, 1890) exemplify this period. They combine realistic observation with a powerful sense of timelessness and harmony between humanity and the immense scale of nature. The figures are often depicted as integral parts of the landscape, embodying the enduring cycles of life and labor in the mountains. The light itself seems to take on a spiritual dimension, suggesting a pantheistic reverence for the natural world.

Symbolism and the Pantheistic Vision

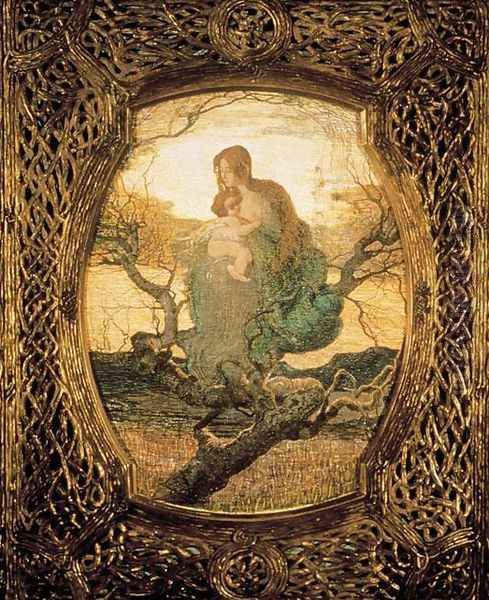

While grounded in the observation of nature, Segantini's art increasingly moved towards Symbolism during his Alpine years. He sought to express universal themes – life, death, love, motherhood, the connection between the human and the divine – through the language of landscape and rural motifs. Nature, for Segantini, was not merely a backdrop but a living entity imbued with spiritual force. His work reflects a pantheistic worldview, seeing divinity diffused throughout the natural world.

Motherhood became a recurring and central theme, often depicted with profound tenderness and symbolic weight. The Two Mothers (Le due madri, 1889) portrays a peasant woman asleep in a stable beside her child, paralleled by a cow resting near her calf. The painting elevates the maternal bond to a universal principle, linking human and animal life within the nurturing embrace of nature. The warm, golden light emanating from the lantern adds a spiritual aura to the humble scene.

Another significant work exploring motherhood and nature is The Angel of Life (L'angelo della vita, 1894). Here, a serene mother figure sits beneath a blossoming tree, cradling her child, while the Alpine landscape unfolds behind them. The image blends Christian iconography (the angelic figure) with pagan or pantheistic elements (the life-giving tree, the sacredness of nature), creating a powerful symbol of creation and continuity.

Segantini's engagement with Symbolism connected him to broader European artistic currents. While developing his unique style in relative isolation, his work shares affinities with Northern Symbolists like the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler, who also depicted monumental Alpine scenes imbued with symbolic meaning, and even the Norwegian Edvard Munch in his exploration of life's fundamental cycles and emotional states. He was also aware of figures like the Swiss-German Arnold Böcklin, whose mythological landscapes resonated with the Symbolist mood.

The Divisionist Technique Perfected

Segantini's commitment to Divisionism was unwavering in his later years. He believed this technique was the most effective way to render the intense luminosity and chromatic richness of the Alpine environment. His method involved applying layers of pure color in distinct, often long, thread-like strokes, allowing the underlying layers or the white ground of the canvas to contribute to the overall vibration of light. This created a textured surface that enhanced the shimmering effect.

His approach differed from French Neo-Impressionism. While both relied on optical mixing, Segantini's brushwork was more dynamic and expressive, less systematic than the dots of Seurat or Signac. His filaments often followed the forms of the objects depicted, enhancing their solidity and texture while simultaneously dissolving them into light. He meticulously studied the effects of light at different times of day and altitudes, striving for scientific accuracy in his color application while simultaneously achieving poetic and spiritual effects.

Segantini became the leading figure of Divisionism in Italy. This movement, while influenced by French developments, had its own distinct character. Other notable Italian Divisionists included Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, famous for his monumental social realist painting The Fourth Estate, Angelo Morbelli, known for his poignant depictions of the elderly and scenes of labor, Gaetano Previati, whose work often leaned towards more overtly religious or mystical Symbolism, and Segantini's old friend Emilio Longoni. Segantini's technical brilliance and powerful vision, however, set him apart.

Contemporaries, Friendships, and Isolation

Despite his relative geographical isolation in the Alps, Segantini maintained connections with the art world, primarily through Vittore Grubicy and correspondence. His friendship with the Bugatti family remained strong. Carlo Bugatti's exotic furniture designs, though stylistically different, shared a certain originality and intensity with Segantini's work.

In Switzerland, Segantini formed a close friendship with the painter Giovanni Giacometti (father of the famous sculptor Alberto Giacometti and artist Diego Giacometti). Giovanni Giacometti was also a Post-Impressionist painter deeply interested in capturing the light and color of the Alps, and the two artists shared mutual respect and influence. Segantini acted as a mentor to the younger Giacometti for a time.

He also maintained contact with his Italian Divisionist colleagues like Gaetano Previati and Emilio Longoni, and with figures in the Milanese art scene such as the sculptor Paolo Troubetzkoy and the painter Luigi Conconi. However, his primary focus remained his work and his life in the mountains with Bice and their children (Gottardo, Alberto, Mario, and Bianca). His statelessness – born Austrian, he never acquired Italian or Swiss citizenship – perhaps contributed to his sense of being an outsider, dedicated wholly to his artistic vision.

Maloja and the Final Masterpiece: The Alpine Triptych

In 1894, Segantini moved his family higher still, to Maloja in the Upper Engadine valley, near St. Moritz, situated at over 1,800 meters (nearly 6,000 feet). He sought ever more pristine light and expansive vistas. It was here that he embarked on his most ambitious project: a monumental cycle intended for the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition. His initial plan was a vast panorama of the Engadine landscape, housed in a dedicated pavilion. Financial and logistical difficulties forced him to scale back this grand vision.

Instead, he focused on creating a large triptych, known as the Triptych of the Alps or The Triptych of Life, Nature, and Death (Il Trittico delle Alpi: La Vita, La Natura, La Morte), completed between 1896 and 1899. This work stands as the culmination of his artistic and philosophical journey. Each panel depicts a different aspect of the Alpine cycle, unified by the overarching landscape and Segantini's signature Divisionist technique, which reached its zenith here.

Life (La Vita), the left panel, shows a scene of tranquil pastoral existence, with figures ascending a mountain path under a luminous sky, suggesting birth and the journey of life. Nature (La Natura), the large central panel, depicts a dramatic, sun-drenched Alpine landscape in late spring or early summer, with shepherds and flocks returning from high pastures at sunset. It represents the majestic, enduring power of nature, rendered with breathtaking detail and light. Death (La Morte), the right panel, portrays a stark winter scene with a shrouded figure on a sled leaving a snow-bound dwelling, set against a backdrop of frozen peaks under a fading twilight sky, symbolizing the end of life's journey and the return to the elements.

The Triptych is a profound meditation on the fundamental rhythms of existence as observed in the high Alps. It seamlessly integrates realistic depiction with symbolic allegory, executed with unparalleled technical mastery. The shimmering light, achieved through countless interwoven strokes of pure color, imbues the entire work with a transcendent, spiritual quality.

Untimely Death on the Mountain

Tragically, Segantini would not live to see the full impact of his final masterpiece. In September 1899, while working outdoors at high altitude on Schafberg mountain above Pontresina, likely making studies related to the Triptych or planning future works, he fell acutely ill. He was brought down to a nearby shepherd's hut. His condition rapidly deteriorated, diagnosed as peritonitis (likely caused by a ruptured appendix). Despite Bice rushing to his side, Giovanni Segantini died on September 28, 1899, at the age of just 41. His reported last words, gazing towards the mountains, were: "I want to see my mountains."

His sudden death shocked the art world. He was at the peak of his creative powers, internationally renowned, and considered one of the most original artists of his time. He was buried in the small cemetery in Maloja, his grave overlooking the Alpine landscapes he loved and painted.

Legacy and Influence

Giovanni Segantini's legacy is significant and multifaceted. He is widely regarded as the most important Italian painter of the late 19th century and a key figure in European Symbolism and Post-Impressionism. His unique development of Divisionism demonstrated a powerful alternative to French Pointillism, emphasizing texture, light, and emotional expression.

His influence was felt immediately, particularly among the next generation of Italian artists. The burgeoning Futurist movement, though ideologically different, looked to Segantini's Divisionist technique as a foundation for their own explorations of dynamism and modern sensations. Leading Futurists like Umberto Boccioni and Carlo Carrà acknowledged their debt to Segantini's handling of light and color.

Segantini's depictions of the Alps remain iconic. He transformed mountain landscape painting from mere topography into a vehicle for profound spiritual and philosophical inquiry. His work influenced subsequent generations of Alpine painters, including his friend Giovanni Giacometti and, to some extent, the powerful symbolic mountainscapes of Ferdinand Hodler.

His international reputation, strong during his lifetime, endured. His works were exhibited across Europe and acquired by major museums. In 1908, the Segantini Museum opened in St. Moritz, Switzerland, designed specifically to house his monumental Alpine Triptych and other major works, cementing his status as the definitive painter of the Engadine region. Today, his paintings are held in prestigious collections worldwide, including the Galleria d'Arte Moderna in Milan, the Kunsthaus Zürich, and the Musée d'Orsay in Paris.

While some early 20th-century critics occasionally dismissed his work as overly sentimental or tied to a vanishing rural world, later reappraisals, particularly from the mid-20th century onwards, have reaffirmed his importance. Art historians now recognize the complexity of his vision, his technical innovation, and his unique position bridging 19th-century realism and symbolism with the emerging currents of modernism.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision

Giovanni Segantini's life was a testament to the power of artistic vision overcoming adversity. From orphaned street child to internationally acclaimed master, he pursued his singular path with unwavering dedication. He found in the high Alps not just subject matter, but a spiritual home and a mirror for the profound mysteries of life, death, and the enduring power of nature. Through his luminous, meticulously crafted paintings, he invites viewers into a world of intense light, rugged beauty, and deep symbolic resonance. As a master of Divisionism and a poignant Symbolist voice, Giovanni Segantini remains a vital and compelling figure in the history of art, the painter who captured the very soul of the mountains.