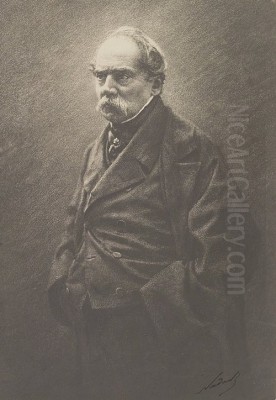

Constantin Guys stands as a unique and somewhat enigmatic figure in the annals of 19th-century art. Born Dutch but intrinsically linked with the vibrant life of Second Empire Paris, he was an artist, illustrator, and war correspondent whose keen eye captured the fleeting moments of modernity. Though he shunned personal fame, preferring anonymity, his work earned him the admiration of the influential poet and critic Charles Baudelaire, who famously dubbed him "The Painter of Modern Life." His drawings and watercolors offer an invaluable, intimate glimpse into the society, fashion, conflicts, and urban pulse of his time.

From Soldiering Adventures to Artistic Awakening

Ernest Adolphe Hyacinthe Constantin Guys was born in Vlissingen, Netherlands, on December 3, 1802. His early life was marked by adventure rather than artistic pursuits. Driven by a restless spirit, he left home at the young age of 18 to embrace the life of a soldier. This path led him to participate in the Greek War of Independence in the early 1820s, a conflict that attracted romantic idealists from across Europe. Notably, he served alongside the celebrated English poet Lord Byron, an experience that undoubtedly exposed him to dramatic events and diverse human conditions.

Following his involvement in Greece, Guys's military career continued. In 1827, he joined a French dragoon regiment. His service took him on extensive travels across Europe and even into the Near East. These journeys provided him with a wealth of visual experiences, observing different cultures, landscapes, and military life. However, during these years, art was not his primary focus; he was a man of action, absorbing the world around him rather than formally documenting it through drawing.

It wasn't until Guys reached his forties, around the early 1840s, that he began to dedicate himself seriously to art. This late start is remarkable, especially considering he lacked formal academic training in painting or draftsmanship. Unlike contemporaries who progressed through established academies, such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres or Eugène Delacroix, Guys was largely self-taught. His artistic education came from life itself – his travels, his military observations, and his innate talent for capturing the essence of what he saw. This unconventional path shaped his unique style, free from rigid academic constraints.

Witness to War: The Crimean Correspondent

Guys's transition into a professional artist coincided with the rise of illustrated journalism. His skills as a rapid, observant sketch artist found a perfect outlet in this burgeoning field. His most significant contribution in this area came during the Crimean War (1853-1856). Commissioned by the Illustrated London News, one of the most prominent pictorial newspapers of the era, Guys traveled to the front lines as a "special artist."

His role was crucial and dangerous. He produced numerous sketches depicting not just battles and military maneuvers, but also the daily life of soldiers, camp scenes, logistical operations, and the broader atmosphere of the conflict zone. These drawings were quickly dispatched back to London, where engravers would translate them into printable images for the newspaper's eager readership. Guys's work provided the public with a visual immediacy that written reports alone could not convey, making him one of the pioneering figures in war correspondence art.

His Crimean sketches were noted for their dynamism and authenticity. He didn't just record static events; he captured the movement, the chaos, and the human element of war. This work brought him considerable recognition, particularly in England and France. It was through these published illustrations that his talent caught the eye of Charles Baudelaire, setting the stage for a pivotal relationship in Guys's career and legacy. His approach differed from the grand, often allegorical war paintings of earlier artists, offering a more direct, journalistic perspective, perhaps echoing the unflinching gaze seen later in photographers like Mathew Brady during the American Civil War, albeit in a different medium.

Baudelaire's Muse: Embodying Modernity

The encounter with Charles Baudelaire proved transformative for Constantin Guys's posthumous reputation, if not his contemporary fame (which he actively avoided). Baudelaire, a leading poet and perhaps the most insightful art critic of his generation, saw in Guys the perfect embodiment of his theories about modern art and the modern artist. In 1863, Baudelaire published his seminal essay, "Le Peintre de la vie moderne" ("The Painter of Modern Life"), ostensibly about Guys, though he respectfully referred to him only as "Monsieur G." to honor the artist's desire for anonymity.

In this essay, Baudelaire articulated his concept of "modernity" – the ephemeral, the fugitive, the contingent, the half of art whose other half is the eternal and the immutable. He argued that the true modern artist should be a passionate spectator, a "flâneur," immersing himself in the urban crowd, extracting the poetic from the historical moment, and capturing the transient beauty of contemporary life. For Baudelaire, Guys exemplified this ideal. He praised Guys's ability to seize the fleeting gestures, the fashionable silhouettes, the atmosphere of the boulevards, the character of soldiers, dandies, and women of all social strata.

Baudelaire admired Guys's technique, particularly his reliance on memory and his rapid, suggestive sketching style, which seemed perfectly suited to capturing the dynamism of modern existence. He saw Guys not merely as an illustrator but as a profound observer of human nature and the social pageant of Paris during the Second Empire (1852-1870). This essay cemented Guys's place in art history, linking him inextricably with the definition of artistic modernity, even though Guys himself remained detached from theoretical debates and artistic movements.

Sketching the Second Empire: Style and Subject Matter

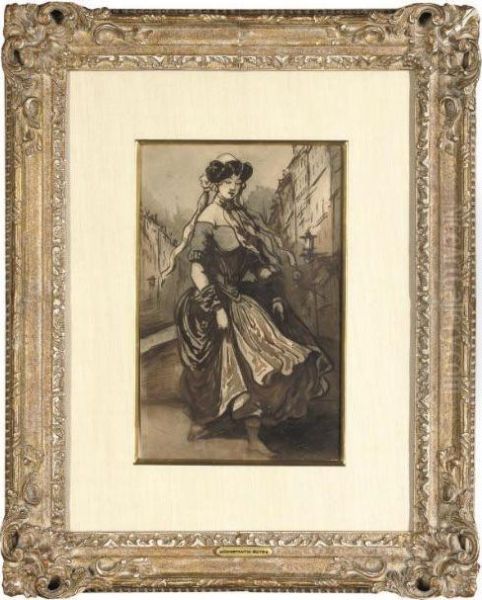

After his experiences in the Crimea, Guys returned to Paris and dedicated himself almost entirely to depicting the life of the French capital during the opulent and rapidly changing era of Napoleon III. His subject matter was vast, reflecting his insatiable curiosity about the world around him. He sketched elegant ladies and gentlemen promenading in the Bois de Boulogne, carriages rolling down the boulevards, scenes from theatres, balls, and cafes. His eye captured the height of fashion – the elaborate crinolines, the bonnets adorned with ribbons, the tailored suits of the men.

However, Guys's gaze was not limited to high society. He was equally fascinated by the demi-monde, the world of courtesans and prostitutes, whom he depicted with an unsentimental yet often sympathetic eye, capturing their elaborate attire, their waiting postures, and their interactions in salons or cafes. He drew soldiers on leave, street vendors, children playing, and the anonymous faces in the crowd. His work provides a panoramic view of Parisian society, from its glittering surface to its less visible undercurrents.

His style was characterized by its immediacy and fluidity. Working primarily in watercolor, ink wash, and pencil or pen, he favored rapid execution. His lines are often energetic and broken, suggesting movement and the transience of the moment. He used washes of color effectively to create atmosphere and highlight details of costume or setting. His compositions often feel spontaneous, like snapshots capturing a scene mid-action. This approach aligns with Baudelaire's description of the modern artist needing to work quickly to grasp the ephemeral nature of contemporary life, a quality that would later be explored differently by Impressionists like Edgar Degas and Claude Monet.

Technique, Anonymity, and Artistic Philosophy

Constantin Guys's working methods were as distinctive as his subject matter. As Baudelaire noted, he often worked from memory. He would observe scenes intently, absorbing details, and then recreate them later in his studio. This process allowed him to filter reality through his own sensibility, emphasizing the essential character and movement of a scene rather than producing a strictly photographic reproduction. His drawings possess a vitality that comes from this combination of sharp observation and imaginative reconstruction.

A defining characteristic of Guys's career was his steadfast commitment to anonymity. He rarely, if ever, signed his finished works. When his illustrations were published, they were often uncredited or attributed simply to "Our Special Artist" or similar generic titles. Even in Baudelaire's essay, he insisted on being referred to as "Monsieur G." This desire for obscurity stemmed from a deep-seated humility and perhaps a belief that the work should speak for itself, detached from the personality cult that was beginning to surround artists. He reportedly felt that signatures were easily forged, while the inherent originality of his style was his true, inimitable mark.

This rejection of public recognition contrasts sharply with the growing self-promotion seen among many artists of the period. Guys seemed content to be an observer, a chronicler moving through the crowd, his identity submerged in the life he depicted. This philosophy aligns with the persona of the flâneur – the detached yet deeply engaged stroller and spectator of the urban spectacle. His focus remained squarely on capturing the essence of modern life, rather than building a personal brand.

Representative Works and Themes

While Guys did not title his works conventionally, certain recurring themes and types of scenes function as his representative output. His depictions of elegant women are particularly notable. Whether riding in open carriages, attending social gatherings, or simply displaying the latest fashions, these figures are rendered with an appreciation for their poise and the elaborate details of their attire. Works often cataloged with descriptive titles like Two Women in a Carriage or Elegant Figures in an Interior showcase this aspect of his oeuvre.

Scenes of Parisian street life form another major category. Drawings like the one sometimes titled In the Street capture the bustle of the boulevards, the mix of social types, and the energy of the modern city. He was fascinated by horses and carriages, rendering them with dynamic lines that convey speed and elegance. Military subjects also remained a constant interest, stemming from his own background. He frequently drew soldiers in uniform, both on parade and in more relaxed, off-duty moments.

His depictions of the demi-monde, such as scenes sometimes described as Women at a Cafe or Prostitutes in a Salon, are among his most discussed works. These drawings offer a glimpse into a side of Second Empire life often veiled in official art. Guys approached these subjects without moralizing, focusing instead on the visual aspects – the elaborate, sometimes garish costumes, the poses, the social dynamics. A work like A Woman with a Parasol (or the description scantily clad woman with men around a table) points to this exploration of different facets of femininity and social interaction in the modern city.

Connections and Context: Guys Among Contemporaries

Constantin Guys operated within a rich artistic and literary milieu, though his connections were often more observational or professional than deeply collaborative. His most significant relationship was undoubtedly with Charles Baudelaire, who acted as his critical champion. Through Baudelaire, Guys's work became associated with the forefront of thinking about modernity in art.

He was also contemporary with other artists known for their depictions of Parisian life and social commentary. Honoré Daumier, famed for his sharp caricatures and paintings of everyday people, shared Guys's interest in observing society, though Daumier's work often carried a stronger satirical or political edge. Paul Gavarni was another prolific illustrator and lithographer known for his witty portrayals of Parisian manners and types, particularly figures from the worlds of fashion and entertainment. Guys knew these artists, and they formed part of a broader circle interested in capturing the contemporary scene.

The photographer Nadar (Gaspard-Félix Tournachon), a friend of Baudelaire and a prominent figure in Parisian cultural life, documented many of the same personalities and the changing city that Guys sketched. While their mediums differed, both Guys and Nadar contributed to the visual record of their time.

Guys's work is often compared to that of James McNeill Whistler, particularly in their shared interest in capturing atmospheric effects and modern subjects, though Whistler worked primarily in painting and printmaking and cultivated a very different public persona. Furthermore, Guys's focus on fleeting moments, urban life, and informal compositions is seen as prefiguring aspects of Impressionism. Artists like Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, who were deeply engaged with depicting modern Parisian life, likely knew Guys's published work. Manet's own depictions of cafes, bars, and social gatherings share thematic ground with Guys, while Degas's interest in dancers, laundresses, and behind-the-scenes views of entertainment resonates with Guys's exploration of different social spheres. Other contemporaries like Eugène Lami, known for elegant watercolors of high society, or the incredibly prolific illustrator Gustave Doré, provide further context for Guys's position within the visual culture of the era. James Tissot, though working slightly later and often in London, also explored similar themes of modern social life and fashion.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and the Preference for Anonymity

True to his character, Constantin Guys largely avoided the official art world structures of his time, such as the Paris Salon. He did not seek to exhibit his original drawings and watercolors in major public venues during his lifetime. His recognition came primarily through the publication of his illustrations in periodicals like the Illustrated London News and French publications such as Le Figaro. This meant his work reached a wide audience, but the artist himself remained largely unknown to the general public.

His association with Baudelaire provided a different kind of recognition within literary and artistic circles. "The Painter of Modern Life" ensured that Guys, or at least "Monsieur G.", became a key reference point in discussions of modern art, even if few knew his actual name or the full scope of his work.

Posthumous recognition grew steadily. Curators and art historians began to appreciate the unique quality and historical importance of his oeuvre. While the provided text mentions a 1964 exhibition at the Museum Fridericianum in Kassel, Germany (documenta III), featuring Guys alongside artists like Valentin Haussmann and Adolf Hensel under curator Arnold Bode, this represents later institutional acknowledgment rather than contemporary participation. Such exhibitions, occurring long after his death, helped solidify his reputation and make his original works accessible to scholars and the public, finally bringing the anonymous chronicler somewhat out of the shadows he had preferred during his life.

The Observer on the Margins: Social Position and Personality

Constantin Guys occupied a somewhat marginal position in society, which arguably enhanced his perspective as an observer. His Dutch origins made him something of an outsider in Paris. His late start in art and his career primarily as an illustrator, rather than a painter exhibiting at the Salon, placed him outside the traditional artistic hierarchy. His peripatetic early life as a soldier also contributed to a sense of detachment.

Sources suggest he was a man of unique personality, marked by humility and a genuine love for the spectacle of life, particularly the energy of crowds. Baudelaire described him as a "man of the world," understanding its codes and rituals, yet also possessing the "curiosity of a child." He was reportedly modest about his talents and uncomfortable with praise. His desire for anonymity seems to have been deeply ingrained in his character, not merely an affectation.

His social network appears to have been characterized by what sociologists call "weak ties" – numerous professional contacts and acquaintances rather than a tight-knit circle of intimate friends, with the possible exception of his bond with Baudelaire. He moved through different social spheres, from battlefields to ballrooms, observing and recording, but perhaps never fully belonging to any single one. This position on the edge allowed him a panoramic view, enabling him to capture the diverse facets of modern life without being entirely absorbed by any particular milieu. His health was also noted as sometimes frail, perhaps further contributing to his role as an observer rather than a full participant.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Constantin Guys continued to draw prolifically throughout his later years, his passion for observing and recording the life around him undiminished. He remained dedicated to his themes, capturing the evolving fashions and social customs of Paris. Despite his preference for anonymity, his distinctive style made his work recognizable to connoisseurs.

His life ended tragically. In 1885, he was involved in a street accident, run over by a carriage on the Rue du Havre. He suffered severe injuries, including the loss of a leg, and spent the last seven years of his life infirm, cared for at the Dubois hospital (now Hôpital Fernand-Widal) in Paris. He died there on March 13, 1892, at the age of 89.

Constantin Guys's legacy is significant, albeit unconventional. He left behind a vast body of work – thousands of drawings and watercolors – that serves as an unparalleled visual diary of his time. He was not a grand history painter or a revolutionary stylist in the mold of the Impressionists who followed, but his contribution is invaluable. Through his keen eye and fluid hand, he captured the essence of modernity as defined by Baudelaire: its fleeting beauty, its nervous energy, its mix of elegance and grit. He showed future generations what it looked like to live in Second Empire Paris and during the conflicts of the mid-19th century. His work continues to fascinate historians, art lovers, and anyone interested in the visual culture of the modern era. He remains, as Baudelaire christened him, the quintessential "Painter of Modern Life."

Conclusion: The Anonymous Eye

Constantin Guys presents a fascinating paradox: an artist celebrated for capturing the public spectacle of modern life, yet who personally shunned the spotlight. His Dutch roots, military past, late artistic start, and preference for illustration over Salon painting set him apart from many contemporaries. Championed by Baudelaire, he became the embodiment of the modern artist as observer, the flâneur whose genius lay in extracting the eternal from the ephemeral pulse of the city and its inhabitants. His unsigned watercolors and drawings, filled with the movement of carriages, the rustle of crinolines, the postures of soldiers, and the anonymous energy of the crowd, offer a vivid, invaluable, and deeply personal chronicle of the 19th century. Though he sought obscurity, Constantin Guys's unique vision secured him a lasting place as a crucial witness to and interpreter of modernity.