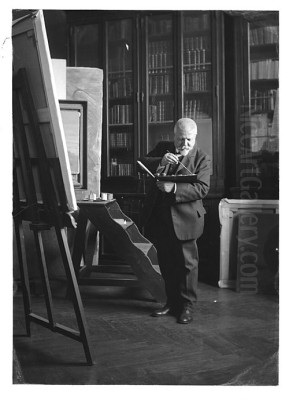

Gaetano Previati stands as a pivotal figure in Italian art at the turn of the 20th century, a painter and theorist whose work bridged the late Romantic sensibilities with the burgeoning modernist movements. His unique approach to Symbolism, deeply intertwined with his pioneering adoption and theoretical articulation of Divisionism, carved a distinct path that influenced a generation of artists. Born in Ferrara and active primarily in Milan, Previati's oeuvre is characterized by its ethereal light, spiritual depth, and innovative technique, leaving an indelible mark on the Italian and broader European artistic landscape.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Gaetano Previati was born on August 31, 1852, in Ferrara, Italy, into a devoutly religious family. This upbringing would later manifest in the spiritual and often mystical themes prevalent in his art. His initial artistic inclinations led him to study in his hometown before venturing to Florence, where he enrolled at the Accademia di Belle Arti. In Florence, he studied under notable masters such as Amos Cassioli, a painter known for his historical and allegorical subjects, which likely provided Previati with a solid academic grounding.

However, it was his move to Milan in 1876 and his subsequent studies at the prestigious Brera Academy (Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera) that proved most formative. In Milan, the artistic environment was vibrant and receptive to new ideas. Previati came under the influence of prominent figures like Giuseppe Bertini, a versatile artist skilled in historical painting and decorative arts. More significantly, he absorbed the stylistic innovations and thematic concerns of Domenico Morelli and Tranquillo Cremona. Morelli, a leading figure of Neapolitan painting, was known for his dramatic historical and religious scenes infused with Romantic emotionalism and a rich, often dark, palette. Cremona, a key exponent of the Scapigliatura movement, was celebrated for his sfumato-like, dematerialized figures and intimate, psychologically charged portraits. The Scapigliati, including Daniele Ranzoni, sought to break from academic conventions, emphasizing atmosphere and emotion over precise delineation. These influences encouraged Previati to move beyond purely historical subjects towards a more personal and expressive artistic language.

The Embrace of Divisionism

The late 1880s marked a crucial turning point in Previati's career with his encounter with Divisionism. This technique, an Italian response to French Neo-Impressionism (Pointillism), was championed in Italy by figures like the critic and gallerist Vittore Grubicy de Dragon. Grubicy was instrumental in promoting the style and introducing its theoretical underpinnings to artists like Previati, Giovanni Segantini, Angelo Morbelli, and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo. Unlike the French Pointillists such as Georges Seurat and Paul Signac, who often used dots of pure color, Italian Divisionists typically employed elongated filaments or threads of color, juxtaposed to create optical vibrancy and luminosity.

Previati was not merely a practitioner but also a key theorist of Divisionism. He delved into the scientific principles of optics and color theory, seeking to understand how light and color could be manipulated to evoke specific emotional and spiritual responses in the viewer. His writings, notably "I principii scientifici del Divisionismo" (The Scientific Principles of Divisionism, 1906), codified the movement's aims and techniques, emphasizing the use of pure, unmixed colors applied in separate strokes to achieve maximum luminosity and a sense of dematerialization. He believed this method could transcend mere representation and tap into deeper symbolic meanings. His first major Divisionist work, Maternità (Motherhood), exhibited at the Brera Triennale in 1891, caused a sensation and firmly established him as a leading figure of the new movement.

Symbolism and Mystical Themes

While Divisionism provided the technical means, Symbolism offered the thematic and philosophical framework for much of Previati's mature work. Emerging across Europe in the late 19th century as a reaction against Naturalism and Realism, Symbolism sought to express ideas, emotions, and spiritual truths through suggestive imagery rather than direct depiction. Artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Puvis de Chavannes in France, or Fernand Khnopff in Belgium, explored themes of dreams, mythology, religion, and the inner life.

Previati was deeply attuned to these currents. His art frequently explored religious narratives, allegorical scenes, and literary subjects, all imbued with a mystical aura. Works such as Christ Crucified (1881), though predating his full embrace of Divisionism, already showed his inclination towards dramatic, emotionally charged religious subjects. Later, his Via Crucis (Stations of the Cross, 1883-1888) further developed these themes. His Symbolist tendencies were also evident in his illustrations for works by authors like Edgar Allan Poe, whose macabre and fantastical tales resonated with the Symbolist sensibility. The ethereal quality achieved through his Divisionist technique—long, flowing brushstrokes that seem to weave light and color into an almost incorporeal tapestry—was perfectly suited to conveying the otherworldly and spiritual dimensions central to Symbolist art.

Key Masterpieces and Their Significance

Gaetano Previati's oeuvre includes several masterpieces that exemplify his artistic vision and technical prowess. These works are celebrated for their innovative use of color and light, their profound symbolism, and their emotional impact.

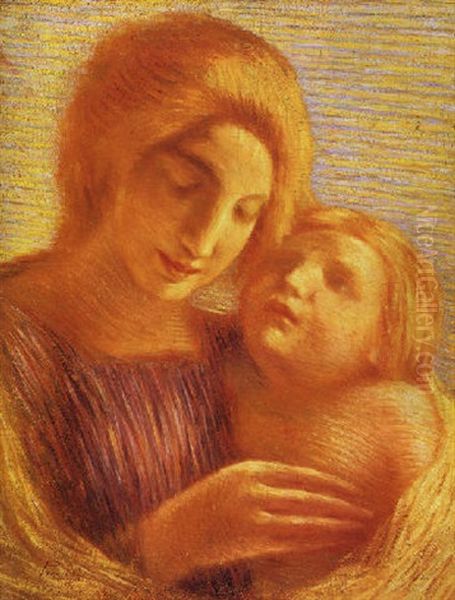

Maternità (Motherhood, 1890-1891): This is arguably Previati's most iconic work and a cornerstone of Italian Divisionism. Exhibited at the Brera Triennale of 1891, it depicts a serene Madonna-like figure cradling an infant, surrounded by a host of ethereal angels whose forms dissolve into flowing lines of light and color. The figures are set against a backdrop of a stylized, blossoming tree, symbolizing life and fecundity. The painting's elongated forms and the radiant, almost incandescent, palette create an atmosphere of sacred tranquility and universal love. The work was both praised for its innovative technique and spiritual depth, and criticized by traditionalists, but it undeniably announced Previati as a major force.

Madonna dei Gigli (Madonna of the Lilies, 1893-1894): Continuing his exploration of religious themes through a Symbolist lens, this painting portrays the Virgin Mary in a field of lilies, traditional symbols of purity. The figures are rendered with Previati's characteristic filamentous brushstrokes, creating a shimmering, dreamlike effect. The emphasis is less on dogmatic representation and more on evoking a sense of spiritual grace and otherworldly beauty. The delicate interplay of light and color contributes to the painting's ethereal quality, making it a powerful example of Symbolist religious art.

La Danza delle Ore (The Dance of the Hours, 1899): Inspired by Amilcare Ponchielli's opera La Gioconda, specifically the ballet sequence, this large-scale work is a dynamic and allegorical representation of the passage of time. Twelve female figures, personifying the hours, dance in a circle around a central, sun-like orb. Previati uses his Divisionist technique to convey movement and light, with the figures appearing almost to dematerialize into streams of energy. The painting is a complex allegory of cosmic harmony, the cyclical nature of time, and the ephemeral beauty of existence. Its vibrant colors and rhythmic composition make it one of his most visually striking works.

Il Re Sole (The Sun King, 1890-1893): This painting, also known as Il Carro del Sole (The Chariot of the Sun), depicts the sun god Apollo driving his fiery chariot across the sky. It is a powerful mythological scene, rendered with dramatic intensity. The horses and chariot seem to emerge from a blaze of light, their forms defined by energetic, swirling brushstrokes. Previati masterfully uses warm, radiant colors to convey the power and majesty of the sun, a recurring motif in Symbolist art representing enlightenment, life, and divine power.

Paolo e Francesca (Paolo and Francesca, 1887, reworked 1909): Based on the tragic story of the adulterous lovers from Dante's Inferno, this work showcases Previati's ability to convey intense emotion. The figures of Paolo and Francesca are enveloped in a swirling vortex, symbolizing their eternal damnation but also the passionate nature of their love. The earlier versions were more traditionally rendered, but the later iterations incorporate his Divisionist technique to heighten the drama and emotional turmoil, with the figures almost dissolving into the turbulent atmosphere. This subject was popular among Romantic and Symbolist artists, including Ary Scheffer and Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Technique, Light, and Color

Previati's artistic style is inextricably linked to his mastery of the Divisionist technique. He did not simply adopt it; he adapted and refined it to suit his expressive needs. His brushwork often consisted of long, thin, thread-like strokes, which he called "pennellata filamentosa" (filamentous brushstroke). These strokes, when juxtaposed, allowed colors to mix optically in the viewer's eye, creating a luminosity and vibrancy that was central to his aesthetic. This technique was particularly effective in depicting ethereal, spiritual, or dreamlike scenes, as it allowed forms to appear less solid and more infused with light.

Light was a primary concern for Previati. He saw it not just as a means of illumination but as a spiritual force, a manifestation of the divine or the transcendent. His paintings often feature figures bathed in an inner radiance or surrounded by a luminous aura. He explored the symbolic potential of different qualities of light – the soft glow of dawn, the brilliant blaze of the sun, the mystical light of a spiritual vision. His deep study of optics and the psychology of perception, as outlined in his theoretical writings, informed his practical application of color to achieve these effects. He sought to stimulate the viewer's retina in a way that would evoke strong emotional and even spiritual responses, moving beyond mere visual representation to a more profound engagement.

International Recognition and Exhibitions

Gaetano Previati achieved considerable recognition during his lifetime, both within Italy and internationally. His participation in major exhibitions was crucial in disseminating his work and ideas. The 1891 Brera Triennale, where Maternità was shown, was a landmark event for Italian Divisionism. He also exhibited regularly at the Venice Biennale, one of the most prestigious international art exhibitions. Notably, at the 1907 Venice Biennale, he was given a dedicated room, the "Sala del Sogno" (Room of Dreams), which showcased his Symbolist and mystical works, solidifying his reputation as a master of this genre.

His involvement extended to international Symbolist circles. He participated in the Salons de la Rose+Croix in Paris, organized by Joséphin Péladan. These Salons were important venues for Symbolist artists from across Europe, promoting art that was idealistic, mystical, and anti-materialist. Previati's work, with its spiritual themes and ethereal style, found a receptive audience in these circles. His interactions with Belgian Symbolists and other European artists further enriched his artistic perspective and contributed to his international standing. Despite some initial controversy, his innovative approach gradually gained acceptance and admiration, positioning him as one of Italy's most significant contemporary artists.

Later Years and the Connection to Futurism

In his later years, Previati's art continued to evolve. While he remained committed to his core principles, his work began to show an engagement with emerging modernist trends, particularly Futurism. The Italian Futurists, including Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Luigi Russolo, Giacomo Balla, and their theorist Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, admired Previati's Divisionist technique, particularly its emphasis on dynamism, light, and the fragmentation of form. Boccioni, in particular, acknowledged Previati's influence on Futurist theories of color and light.

Previati's painting The Pacific Railway (Il Treno del Pacifico, 1914-1915), depicting a speeding train, is often cited as an example of his engagement with Futurist themes of modernity, speed, and technology. While not a Futurist work in the strict sense, its dynamic composition and the attempt to capture the sensation of motion show a kinship with Futurist concerns. This demonstrates Previati's openness to new artistic currents, even as he maintained his distinctive style. His theoretical writings on Divisionism also provided a foundation upon which the Futurists built their own theories of "universal dynamism" and the emotional power of color.

Theoretical Writings and Lasting Legacy

Gaetano Previati was not only a prolific painter but also an important art theorist. His writings, especially "I principii scientifici del Divisionismo" (1906) and "Della pittura: Tecnica ed arte" (On Painting: Technique and Art, 1913), were significant contributions to art theory in Italy. In these texts, he articulated the scientific and aesthetic principles of Divisionism, advocating for a painting technique grounded in optical science but aimed at achieving spiritual and emotional expression. He argued for the superiority of Divisionism in rendering light and creating vibrant, luminous surfaces that could convey profound symbolic meanings.

His theories influenced not only his Divisionist contemporaries like Segantini, Pellizza da Volpedo, and Morbelli, but also the subsequent generation of Futurist artists. The Futurists, while seeking to break radically with the past, found in Previati's work and writings a precedent for their own explorations of light, color, and dynamism. Previati's emphasis on the emotional and psychological impact of color resonated with their desire to create art that could directly engage the viewer's senses and emotions.

Gaetano Previati passed away on June 21, 1920, in Lavagna, Liguria. His legacy is that of a visionary artist who masterfully combined technical innovation with profound spiritual and symbolic content. He played a crucial role in introducing and developing Divisionism in Italy, transforming it into a vehicle for Symbolist expression. His work continues to be celebrated for its ethereal beauty, its spiritual depth, and its pioneering approach to color and light. Retrospectives of his work, such as a significant one held in 2020, continue to affirm his importance in the history of modern Italian art, recognizing him as a bridge between 19th-century traditions and 20th-century modernism, and a peer to other great European Symbolists like Edvard Munch or Gustav Klimt in his pursuit of an art that spoke to the soul. His influence can be seen in the works of many subsequent Italian artists, and his contributions to both painting and art theory remain a subject of study and admiration.