Jacopo del Sellaio, born Jacopo di Arcangelo around 1441 in the vibrant artistic crucible of Florence, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure of the Early Italian Renaissance. Active until his death in 1493, Sellaio's career coincided with a period of extraordinary artistic innovation and production in Florence. His moniker, "Sellaio," meaning "saddler," was inherited from his father, Arcangelo di Jacopo, a craftsman whose trade provided the family's name in common parlance, a typical practice in an era where surnames were often derived from occupation, lineage, or place of origin. Sellaio's oeuvre, characterized by its devotional sincerity, narrative charm, and decorative appeal, offers a valuable window into the tastes and artistic practices of late Quattrocento Florence.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Florence in the mid-15th century was a city teeming with artistic guilds, workshops, and ambitious patrons. It was into this environment that Jacopo del Sellaio was born. The first documented mention of him appears in his family's 1446 tax return (catasto), where he is listed as being five years old. This places his birth year around 1441 or 1442. Growing up in a craftsman's household likely instilled in him a strong work ethic and an appreciation for skilled artisanship, qualities that would become evident in his prolific output as a painter.

His formal artistic training is understood to have been under the tutelage of Fra Filippo Lippi, one of the leading painters in Florence during the mid-15th century. Lippi's influence is palpable in Sellaio's early works, particularly in the lyrical grace of his figures, the gentle expressions, and a certain sweetness of color. Fra Filippo Lippi himself was a master of conveying human emotion and creating harmonious compositions, often imbued with a tender, approachable religiosity. Sellaio would have absorbed these qualities, adapting them to his own developing style.

By 1460, Jacopo del Sellaio had matured enough as an artist to join the Compagnia di San Luca (Confraternity of Saint Luke), the painter's guild in Florence. Membership in such an organization was essential for any artist wishing to practice professionally, secure commissions, and establish a workshop. This marked his official entry into the competitive Florentine art world.

Influences and Artistic Milieu

The artistic landscape of Florence during Sellaio's formative years and active career was dominated by several towering figures and evolving stylistic trends. Beyond the foundational influence of Fra Filippo Lippi, Sellaio's work reveals an attentiveness to the innovations of his contemporaries. Most notably, Sandro Botticelli, a fellow pupil of Lippi and a near-contemporary, exerted a profound and lasting impact on Sellaio's style. Botticelli's elegant linearity, his distinctive figure types often imbued with a melancholic grace, and his sophisticated handling of mythological and allegorical themes, resonated with Sellaio. While Sellaio never fully achieved Botticelli's level of poetic intensity or intellectual depth, he skillfully adapted elements of Botticelli's manner, particularly in the rendering of flowing drapery, delicate facial features, and complex narrative compositions.

Later in his career, Sellaio also appears to have absorbed influences from other prominent Florentine masters such as Domenico Ghirlandaio. Ghirlandaio was renowned for his clear, well-organized compositions, his skill in portraiture, and his detailed depictions of contemporary Florentine life, often incorporated into religious scenes. Sellaio's later works sometimes exhibit a greater solidity in figures and a more straightforward narrative presentation that may reflect an awareness of Ghirlandaio's popular style. The artistic environment also included masters like Andrea del Verrocchio, a sculptor and painter whose workshop trained Leonardo da Vinci, and the Pollaiuolo brothers, Antonio and Piero, known for their dynamic figures and anatomical precision. Filippino Lippi, the talented son of Fra Filippo, also became a leading painter, continuing and evolving his father's legacy.

Sellaio was not an isolated artist but an active participant in this vibrant scene. His ability to assimilate and reinterpret various stylistic currents, while maintaining his own recognizable hand, speaks to his versatility and his engagement with the artistic developments around him. He was, in essence, a painter who understood the prevailing tastes of his patrons and skillfully catered to them.

Workshop, Collaborations, and Professional Life

Like most successful artists of the Renaissance, Jacopo del Sellaio operated a busy workshop (bottega). These workshops were hubs of artistic production, where apprentices learned their craft, assistants helped execute commissions, and masters oversaw the quality and style of the output. Sellaio's workshop was evidently a productive one, responsible for a considerable number of paintings.

Documentation reveals several formal partnerships throughout his career. A significant collaboration was with Filippo di Giuliano, which began in 1473 and lasted until Sellaio's death in 1493. Such partnerships were common, allowing artists to pool resources, share workshop space, and tackle larger or more numerous commissions. The nature of these collaborations often meant that distinguishing the individual hands within workshop productions can be challenging for art historians. Before this long-term association, Sellaio is also recorded as having worked with Biagio d’Antonio around 1472. Biagio d'Antonio was another Florentine painter active in the circle of Verrocchio and Ghirlandaio, known for his work on cassoni and devotional panels.

In 1490, towards the end of his career, Sellaio and Filippo di Giuliano took on another partner, Zanobi di Giovanni. While many works specifically attributed to Zanobi have not survived or been identified, his inclusion in the partnership suggests an expansion of their workshop's capacity or perhaps a specialization he brought to the team. Sellaio is also noted to have collaborated with Ghirardo da Parma, particularly on domestic scenes, and with artists like Ludovico del Robbia, a member of the famous family of ceramicists, for smaller religious images, indicating a breadth of professional connections.

His first known independent commission dates to December 10, 1447, for two panel paintings depicting an angel and the Virgin for the church of Santa Lucia a Lucignano. This early commission, if the date is precise and refers to him rather than another Jacopo, would suggest a precocious talent, though some scholars place his birth slightly earlier or this commission later to align with a typical apprenticeship period. However, the provided information suggests this early start.

Thematic Specializations: Cassoni and Domestic Art

Jacopo del Sellaio carved a niche for himself in the Florentine art market, becoming particularly well-known for certain types of paintings. He excelled in "domestic painting," creating works intended for the homes of Florence's increasingly affluent citizenry. This category included devotional panels, mythological scenes, and, most notably, painted panels for cassoni, or marriage chests.

Cassoni were elaborate, decorated chests, often commissioned in pairs, that formed an essential part of a wealthy bride's dowry. They were used to store clothing, linens, and other valuable household items. The front and sometimes side panels of these chests were typically adorned with narrative scenes drawn from classical mythology, ancient history, biblical stories, or chivalric romances. These scenes often carried moralizing messages or celebrated themes of love, marriage, and virtue. Sellaio was a prolific painter of cassoni panels. His style, with its clear storytelling, decorative qualities, and often lively figures, was well-suited to this genre. These panels were not considered "high art" in the same way as large-scale altarpieces or frescoes, but they were highly valued by patrons and provide invaluable insights into the culture, values, and literary tastes of Renaissance Florentines.

His skill in continuous narrative, where multiple episodes of a story are depicted within a single pictorial field, was particularly effective for cassoni. Figures would often reappear in different parts of the panel, guiding the viewer through the unfolding tale. This technique, common in medieval and early Renaissance art, was masterfully employed by Sellaio.

Religious Paintings and Devotional Works

Alongside his work for domestic settings, Jacopo del Sellaio produced a significant body of religious art. These ranged from larger altarpieces for churches to smaller panels intended for private devotion in homes or private chapels. His religious works often display a gentle piety and a direct emotional appeal, characteristics inherited from his master, Fra Filippo Lippi.

Many of Sellaio's religious paintings feature the Madonna and Child, a perennially popular subject. These depictions, such as the Madonna and Child in the church of San Frediano, often emphasize the tender relationship between mother and infant, rendered with soft modeling and a harmonious palette. He also frequently included the young Saint John the Baptist, Florence's patron saint, in these compositions, as seen in works generically titled Madonna and Child with the Young Saint John the Baptist. These paintings served as focal points for prayer and reflection, and Sellaio's approachable style made them highly suitable for this purpose.

Other religious subjects he tackled include scenes from the lives of saints. A notable example is St Jerome in the Wilderness. This theme, popular in the Renaissance, depicted the penitent saint in a rugged landscape, often accompanied by his lion. Sellaio's interpretations would have focused on Jerome's scholarly devotion and ascetic piety. He also painted works like the Assumption of the Virgin for the Pieve di San Giovanni Battista (formerly referred to as Santa Maria delle Grazie) in San Giovanni Valdarno, and a panel of Saint Paul and the Angel Raphael (though more commonly, the Archangel Raphael is paired with Tobias, as in Sellaio's Tobias and the Angel paintings; the specific pairing with St. Paul as cited in the source material is less typical but noted here) for the church of Santa Maria del Carmine in Florence. These commissions for ecclesiastical settings demonstrate his standing as a respected painter of sacred subjects.

Notable Works and Stylistic Characteristics

Jacopo del Sellaio's artistic output was considerable, and many of his works are now housed in museums and private collections around the world. His style is generally characterized by its clear outlines, bright and often decorative coloring, and elongated, graceful figures that show the influence of Botticelli. He often paid close attention to details of costume, landscape, and architecture, adding to the narrative richness of his scenes. While perhaps not an innovator on the scale of Leonardo or Michelangelo, Sellaio was a highly competent and appealing painter who consistently produced works of quality.

Among his most famous and representative works are the narrative panels. The Story of Cupid and Psyche, with panels now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, and elsewhere, showcases his ability to render complex mythological tales with charm and vivacity. These panels, likely from a cassone or a similar piece of painted furniture, depict multiple episodes from Apuleius's story, following Psyche through her trials to her eventual union with Cupid. The landscapes are often fanciful, and the figures move with a delicate, dance-like quality.

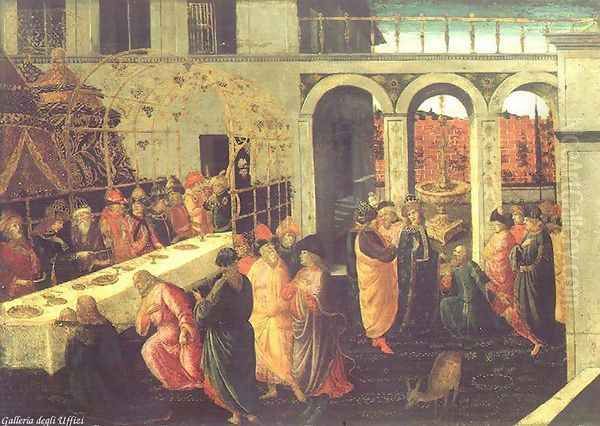

Another significant series of narrative panels illustrates the Story of Esther. Works such as The Banquet of Ahasuerus (c. 1490) and The Triumph of Mordecai (also known as Mordecai Riding through the City) are prime examples of Sellaio's storytelling prowess. These panels, likely from spalliere (wainscoting panels) or cassoni, are filled with numerous figures, elaborate architectural settings, and rich details of costume and courtly life. They demonstrate his skill in organizing complex compositions and conveying dramatic narratives. The Uffizi Gallery in Florence holds important panels from this series.

His painting Orpheus and the Beasts, now in the Wawel Royal Castle, Krakow, Poland, depicts the mythical poet and musician Orpheus charming wild animals with his lyre. This subject allowed Sellaio to showcase his ability to render a variety of animals within a pastoral landscape, a theme that resonated with the Renaissance interest in classical mythology and the harmony of nature.

Many smaller devotional works, such as numerous Madonna and Child panels, are attributed to him and his workshop. These often feature delicate gold-leaf tooling in halos and borders, a testament to the enduring appeal of late Gothic decorative elements even within the evolving Renaissance aesthetic. His works often employed the tempera on panel technique, which allowed for precise detail and luminous color, though oil painting was gaining traction during his lifetime.

Later Career, Legacy, and Posthumous Reputation

Jacopo del Sellaio remained active in Florence until his death on November 12, 1493. He was buried in the church of San Frediano, a testament to his standing within his local community. His workshop continued to be productive throughout his later years, and he passed on his artistic skills to his son, Arcangelo di Jacopo del Sellaio, who also became a painter, though less famous than his father. Arcangelo likely trained in his father's workshop and continued its traditions to some extent.

In the centuries following his death, Jacopo del Sellaio's name, like those of many competent but not superstar artists of the Renaissance, somewhat faded from prominence, overshadowed by the giants who followed. However, the renewed scholarly interest in the Italian Renaissance from the 19th century onwards led to a re-evaluation of artists like Sellaio. Art historians began to appreciate his role in the broader artistic ecosystem of Florence, his skill in specific genres like cassone painting, and the charm and quality of his individual works.

Today, his paintings are found in prestigious collections worldwide, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Uffizi Gallery and the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence, the Courtauld Gallery in London, and the Philadelphia Museum of Art, among many others. This dispersal of his works attests to their enduring appeal to collectors and their importance for understanding the range and richness of Florentine Quattrocento painting.

While Sellaio may not have radically altered the course of art history in the way that artists like Masaccio, Donatello, or Leonardo da Vinci did, his contribution is nonetheless significant. He was a master of narrative, a skilled craftsman, and a painter who beautifully captured the devotional spirit and decorative tastes of his time. His works provide a crucial link in understanding the artistic production that catered to a wide range of patrons in Renaissance Florence, from church commissions to the decoration of private homes. He represents the skilled, reliable, and often delightful artistry that formed the backbone of one of art history's most fertile periods. His engagement with the styles of Lippi and Botticelli, and his collaborations with artists like Biagio d'Antonio and Filippo di Giuliano, place him firmly within the mainstream of Florentine artistic practice, making him an indispensable figure for a comprehensive understanding of Early Renaissance art.