Piero di Cosimo, born Piero di Lorenzo di Piero d'Antonio in Florence around 1462, stands as one of the most idiosyncratic and fascinating painters of the Italian Renaissance. His life, shrouded in a degree of mystery and embellished by the vivid accounts of Giorgio Vasari, was one of artistic innovation and peculiar personal habits. His work, a unique blend of mythological fantasy, keen observation of nature, and poignant religious sentiment, continues to captivate and intrigue art historians and enthusiasts alike. He navigated the vibrant artistic milieu of late fifteenth and early sixteenth-century Florence, absorbing influences from his contemporaries while forging a path distinctly his own.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Piero was born into the bustling city of Florence, the epicenter of the Renaissance, on January 2, 1462. His father, Lorenzo di Piero d'Antonio, was a goldsmith, a common craft background for many aspiring artists of the period, as it provided foundational training in design and precision. His mother was the adopted daughter of a woman named Giuseppa. The young Piero did not follow his father into the goldsmith trade but instead was drawn to the burgeoning world of painting.

Around 1480, Piero became an apprentice in the workshop of Cosimo Rosselli, a respected Florentine painter. It was from his master that Piero adopted the name "di Cosimo," a common practice for apprentices to be identified by their master's name. Rosselli's workshop was a significant training ground, and his style, while perhaps not as groundbreaking as some of his contemporaries, was solid and well-regarded. Rosselli was a competent painter of altarpieces and frescoes, known for a somewhat conventional but clear narrative style.

The Roman Sojourn and Sistine Chapel

A pivotal moment in Piero di Cosimo's early career came when he accompanied Cosimo Rosselli to Rome between 1481 and 1482. Pope Sixtus IV had summoned a team of the leading painters from Florence and Umbria to decorate the walls of his newly built private chapel in the Vatican, the Sistine Chapel. This ambitious project brought together an extraordinary constellation of artistic talent, including Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Pietro Perugino, and Luca Signorelli, alongside Rosselli.

Piero, still a young assistant, is credited with contributing to Rosselli's frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. Specifically, art historians believe he had a significant hand in the landscape portions of Rosselli's Sermon on the Mount and the Healing of the Leper and possibly assisted with The Crossing of the Red Sea. Working alongside such luminaries, even in a subordinate role, would have been an invaluable experience. He would have witnessed firsthand the techniques, compositional strategies, and artistic visions of the era's greatest masters. The competitive yet collaborative atmosphere of the Sistine Chapel project undoubtedly left a lasting impression on the young artist.

Influences Shaping a Unique Vision

The artistic environment of Florence and Rome in the late 15th century was rich with diverse influences, and Piero di Cosimo proved to be a keen observer and an eclectic synthesizer. His early exposure to the work of Sandro Botticelli is evident in a certain lyrical quality and interest in mythological themes, though Piero's interpretations would often take a more earthy and less idealized turn than Botticelli's Neoplatonic allegories.

Domenico Ghirlandaio, another giant of the Florentine school and a fellow contributor to the Sistine Chapel, was known for his masterful draftsmanship, his ability to organize complex narrative scenes, and his inclusion of detailed contemporary portraits within religious subjects. While Piero's path diverged significantly from Ghirlandaio's more classical and socially observant style, the emphasis on clear storytelling and detailed rendering may have resonated with him.

A particularly significant influence on Piero, and indeed on many Florentine artists of the period, was the Netherlandish painter Hugo van der Goes. Van der Goes's Portinari Altarpiece, which arrived in Florence around 1483 and was installed in the church of Sant'Egidio, caused a sensation. Its meticulous realism, the detailed rendering of textures, landscapes, and still life elements, and the expressive, almost raw, emotion of its figures, executed in the oil medium, offered a powerful alternative to Italian tempera traditions. Piero di Cosimo was clearly captivated by this Northern naturalism, and its impact can be seen in his own detailed landscapes, his fascination with animals, and his nuanced use of light and atmosphere, suggesting an early adoption and mastery of oil painting techniques.

The towering figure of Leonardo da Vinci also cast a long shadow over Florentine art. Leonardo's scientific curiosity, his studies of anatomy and natural phenomena, his innovative use of sfumato to create soft, atmospheric effects, and the psychological depth of his figures, were revolutionary. While Piero's temperament was vastly different, Leonardo's emphasis on direct observation of nature and his exploration of the expressive potential of the human form likely informed Piero's own unique approach to rendering the natural world and his often-unconventional figures.

Filippino Lippi, son of Fra Filippo Lippi and a contemporary of Piero, was another artist known for his imaginative and sometimes agitated style, rich in decorative detail and expressive energy. There's a shared sensibility in their departure from the serene classicism of some of their peers, a willingness to explore more dynamic and emotionally charged compositions.

Return to Florence and Maturation of Style

Upon his return to Florence, Piero di Cosimo established himself as an independent master. He began to develop a highly personal style, characterized by a fertile imagination, a love for the bizarre and the fantastical, and a deep engagement with classical mythology and literature, particularly Ovid's Metamorphoses and Vitruvius's accounts of early human history.

His paintings often depict a primeval world, populated by satyrs, centaurs, fauns, and other hybrid creatures, alongside early humans struggling with the elements and discovering the rudiments of civilization, such as the use of fire and tools. These works are not merely illustrative but are imbued with a strange, dreamlike quality, a sense of wonder mixed with a primal energy.

Mythological Narratives and Primeval Fantasies

Piero di Cosimo is perhaps best known for his mythological paintings, which are among the most original and imaginative of the Renaissance. He did not simply recount classical myths but reinterpreted them through his own eccentric lens, often focusing on the more obscure or unsettling aspects of the stories.

A celebrated example is The Death of Procris (National Gallery, London), a poignant and enigmatic work. It depicts the tragic moment from Ovid where Cephalus accidentally kills his beloved wife Procris with a javelin, mistaking her for a wild animal. Piero renders the scene with a tender melancholy. Procris lies dying, attended by a mournful faun and a loyal dog. The landscape is meticulously detailed, evoking a sense of stillness and sorrow. The inclusion of the sympathetic faun is a characteristic touch, highlighting Piero's interest in the creatures that bridge the human and animal worlds.

Another significant mythological work is Perseus Freeing Andromeda (Uffizi, Florence). This painting, likely commissioned for a prominent Florentine family, showcases Piero's ability to create a complex, dynamic narrative. Perseus, mounted on a winged creature (not Pegasus, but a more fantastical invention), swoops down to rescue Andromeda from a bizarre and terrifying sea monster. The scene is filled with onlookers displaying a range of emotions, and the landscape is a typically imaginative creation, with strange rock formations and a turbulent sea. The monster itself is a masterpiece of grotesque invention, typical of Piero's fascination with the monstrous and the fantastical.

His series of paintings depicting scenes from the early history of humankind, likely inspired by Vitruvius, are particularly distinctive. These include A Hunting Scene and The Return from the Hunt (both Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), and The Forest Fire (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford). These panels, possibly intended for spalliere (decorative painted wainscoting), show a world of primitive humans, satyrs, and centaurs coexisting, battling wild animals, and discovering fire. The scenes are chaotic and energetic, filled with a sense of raw, untamed nature. Piero's depiction of animals in these works is particularly noteworthy, showing a keen observation and an ability to convey their wildness and vitality.

The Discovery of Honey by Bacchus (Worcester Art Museum, Massachusetts) is another whimsical mythological piece. It shows a lively scene where Bacchus and his retinue, including Ariadne, satyrs, and maenads, discover a swarm of bees in a hollow tree. The painting is a celebration of nature's bounty and the joyous, untamed spirit of the Bacchic cult, rendered with Piero's characteristic charm and attention to natural detail.

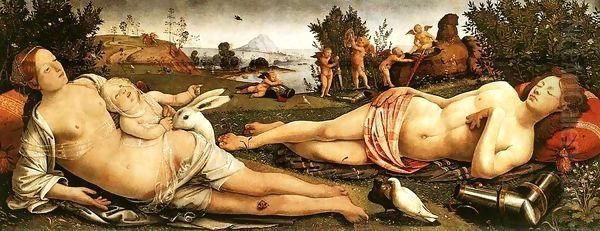

Venus, Mars, and Cupid (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin) presents a more tranquil mythological scene. Venus, the goddess of love, lies asleep, while Mars, the god of war, is also slumbering, his armor cast aside, symbolizing the power of love to pacify strife. Cupid and a group of playful putti surround them, and the background features a detailed landscape with rabbits, a common symbol of fertility. The painting exudes a gentle sensuality and a peaceful atmosphere.

Religious Commissions and Portraiture

While famed for his mythological and fantastical scenes, Piero di Cosimo also produced a significant body of religious works, including altarpieces and devotional paintings. These works often display the same originality and attention to detail found in his secular paintings, though sometimes tempered by the more conventional demands of religious iconography.

His Immaculate Conception with Saints (Uffizi, Florence) is a notable example, demonstrating his ability to handle complex theological themes with visual inventiveness. The influence of Savonarola, the Dominican friar whose fiery sermons advocating for religious reform and denouncing worldly vanities had a profound impact on Florence in the 1490s, can perhaps be detected in the more somber and intensely spiritual mood of some of Piero's religious works from this period.

Piero also undertook portraiture, although fewer examples survive or are securely attributed. His Portrait of Simonetta Vespucci as Cleopatra (Musée Condé, Chantilly) is a famous, if debated, example. It depicts the celebrated Florentine beauty, who died young and was an object of poetic admiration, in the guise of Cleopatra, with an asp entwined around her neck. The portrait is striking for its idealized beauty and its enigmatic symbolism. Another portrait, Giuliano da Sangallo and Francesco Giamberti (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), shows his capacity for capturing individual likeness with a degree of psychological insight.

The Eccentric Genius: Personality and Anecdotes

Much of what we know, or think we know, about Piero di Cosimo's personality comes from Giorgio Vasari's Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects. Vasari, writing several decades after Piero's death, portrayed him as a profoundly eccentric and reclusive individual, a characterization that has largely defined Piero's image for posterity.

According to Vasari, Piero was intensely solitary, shunning human company and preferring the quiet of his own thoughts and his somewhat wild, unkempt studio and garden. He was said to have a phobia of thunderstorms, cowering in fear at the sound of thunder. His diet was reportedly frugal and peculiar; Vasari claims he lived primarily on hard-boiled eggs, which he would cook fifty at a time while boiling his glue, to save on fuel, and then eat them one by one.

Vasari also recounts Piero's aversion to common noises: the crying of babies, the coughing of men, the sound of bells, and the chanting of friars. He supposedly let his garden grow wild, believing that nature should be left to its own devices, and found inspiration in the strange shapes of clouds or the patterns on stained walls, a practice reminiscent of Leonardo da Vinci's advice to artists.

While Vasari's accounts are often embellished for dramatic effect and should be treated with some caution, they paint a picture of an artist deeply absorbed in his own imaginative world, perhaps somewhat out of step with the social norms of his time. This reclusiveness and eccentricity, whether exaggerated or not, seem to find an echo in the unique and often unconventional nature of his art.

The Carnival Designer: The Triumph of Death

Beyond his panel paintings, Piero di Cosimo was also known for his inventive designs for public festivals and carnivals, which were a significant part of Florentine civic life. Vasari gives a particularly vivid description of a macabre and spectacular carnival float designed by Piero, known as The Triumph of Death.

This procession, organized for the Carnival of 1511, featured a large black chariot drawn by black buffaloes, painted with white skeletons and crosses. Atop the chariot sat a colossal figure of Death, scythe in hand, surrounded by tombs that would periodically open to reveal figures dressed as corpses, who would then rise and chant mournful songs about mortality. The procession was illuminated by torches and accompanied by figures dressed as skeletons on horseback. According to Vasari, this terrifying yet fascinating spectacle was a huge success, both frightening and delighting the Florentine populace, and became a legendary event in the city's history. This demonstrates Piero's theatrical imagination and his ability to create powerful, immersive experiences.

Artistic Techniques and Workshop

Piero di Cosimo was a skilled draftsman and a master of the oil painting technique, which he likely adopted and refined after exposure to Netherlandish art. His use of color could range from vibrant and jewel-like in his mythological scenes to more subdued and atmospheric in his religious works and portraits. His landscapes are particularly noteworthy, often imbued with a sense of mystery and filled with meticulously observed details of plants, animals, and geological formations.

Like most successful artists of his time, Piero would have maintained a workshop and trained apprentices. His most famous pupil was Andrea del Sarto, who would go on to become one of the leading figures of the High Renaissance in Florence, known as "il pittore senza errori" (the painter without errors) for his flawless technique and harmonious compositions. The influence of Piero's imaginative approach and his rich handling of color can be discerned in some of Andrea del Sarto's early works.

Other artists associated with Piero's circle or influenced by him include Fra Bartolomeo and Mariotto Albertinelli, who were significant figures in Florentine painting at the turn of the 16th century. Fra Bartolomeo, in particular, shared with Piero an interest in expressive figures and rich, atmospheric landscapes, though his art was more consistently geared towards profound religious devotion.

Later Years and Legacy

Vasari suggests that Piero became even more reclusive and eccentric in his later years. He continued to paint, focusing on his personal artistic vision. Piero di Cosimo died in Florence, likely from the plague, in 1521 or 1522 (the exact date is debated, though 1521 is often cited from the provided text). He was buried in the church of San Pier Maggiore, a church that was unfortunately demolished in the 18th century.

Piero di Cosimo's artistic legacy is significant, though perhaps less direct than that of some of his more mainstream contemporaries. His unique blend of fantasy, naturalism, and psychological insight set him apart. He demonstrated that the themes of classical mythology could be explored with a depth of imagination and a personal inflection that went beyond mere illustration. His fascination with the primitive and the untamed aspects of nature and humanity prefigured later artistic trends.

While he influenced his direct pupils like Andrea del Sarto, his broader impact can be seen in the way he expanded the thematic and expressive possibilities of painting. The early Mannerist painters who emerged in Florence shortly after his death, such as Jacopo Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, with their often unsettling compositions, elongated figures, and intense emotionalism, may have found a kindred spirit in Piero's idiosyncratic vision. Pontormo, in particular, was a pupil of Andrea del Sarto and thus indirectly in Piero's lineage.

Piero's work fell into relative obscurity for centuries after his death, overshadowed by the giants of the High Renaissance like Raphael and Michelangelo. However, he was rediscovered in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly by art historians and artists drawn to his imaginative and unconventional qualities. The Surrealists, for example, found in Piero a precursor to their own explorations of the subconscious and the dreamlike.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision in the Renaissance

Piero di Cosimo remains an enigmatic figure, an artist whose work defies easy categorization. He was a product of the Florentine Renaissance, yet he stood somewhat apart from its main currents, cultivating a highly personal and imaginative style. His paintings, with their strange beauty, their blend of meticulous detail and fantastical invention, and their often-unsettling psychological undertones, offer a unique window into the creative ferment of his time.

He absorbed lessons from masters like Cosimo Rosselli, was exposed to the innovations of Leonardo da Vinci and the Netherlandish painters, and worked alongside luminaries like Botticelli and Ghirlandaio. Yet, he transformed these influences into something entirely his own. Whether depicting the tragic fate of Procris, the primeval struggles of early humans, or the bizarre revelries of mythological creatures, Piero di Cosimo brought to his subjects an unparalleled imaginative power and a deep, if unconventional, sensitivity. His life may have been marked by eccentricity, but his art reveals a profound and original mind, securing his place as one of Rthe enaissance's most fascinating and enduringly modern masters.