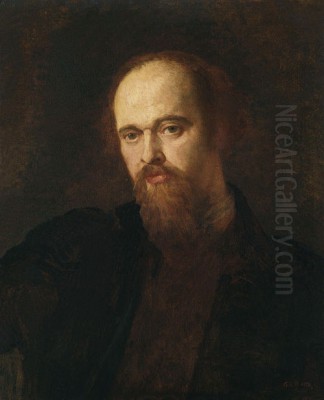

Dante Gabriel Rossetti stands as one of the most compelling and complex figures in nineteenth-century British art and literature. A man of prodigious talent, he excelled as both a painter and a poet, leaving an indelible mark on the Victorian era. Born Gabriel Charles Dante Rossetti in London on May 12, 1828, he later rearranged his name to place the resonant 'Dante' first, signalling his lifelong reverence for the great Italian poet Dante Alighieri. Rossetti was a driving force behind the formation of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group of artists who sought to revolutionize British art, and his work continues to fascinate through its intense emotionalism, sensuous beauty, and deep engagement with medieval and literary themes. His life, as dramatic and passionate as his art, further adds to his enduring mystique.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Rossetti was born into a highly intellectual and artistic Anglo-Italian family. His father, Gabriele Rossetti, was an Italian poet and political exile from Naples who became a professor of Italian at King's College London. His mother, Frances Polidori, was the sister of John Polidori, Lord Byron's physician and author of The Vampyre. This dual heritage immersed the young Rossetti in both English and Italian language and culture from an early age. He grew up alongside three equally gifted siblings: Maria Francesca, a writer and nun; William Michael, a prominent art critic and writer who became his brother's biographer and editor; and Christina, who would become one of the foremost poets of the Victorian era.

Showing artistic promise early on, Rossetti attended King's College School and later enrolled in Sass's Drawing Academy. He gained admission to the Antique School of the Royal Academy of Arts in 1842 but grew impatient with the rigid academic training. He left the Academy schools prematurely, seeking more direct guidance. A pivotal moment came when he encountered the work of Ford Madox Brown, an independent artist whose style showed affinities with the German Nazarenes. Rossetti sought Brown out, briefly becoming his pupil in 1848. Although the formal tutelage was short-lived, Brown remained a lifelong friend and mentor, significantly influencing Rossetti's early development.

Rossetti's early artistic inclinations were already leaning towards the medieval and the literary, themes that would dominate his career. He was drawn to romantic tales, biblical narratives, and, above all, the works of Dante Alighieri and his contemporaries, which he began translating with remarkable skill even in his youth. This deep immersion in literature provided a rich wellspring of subjects for his future paintings and poems.

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

In the autumn of 1848, disillusioned with the prevailing artistic standards promoted by the Royal Academy, which they felt had become formulaic and trivial, Rossetti joined forces with two fellow students, William Holman Hunt and John Everett Millais. Together, they formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB). This secret society aimed to reject the mechanistic approach they believed stemmed from the followers of Raphael and instead emulate the perceived purity, intense colour, intricate detail, and spiritual sincerity of early Italian art before Raphael – artists like Giotto and Botticelli.

The core group soon expanded to include James Collinson, Frederic George Stephens (later an art critic), the sculptor Thomas Woolner, and Rossetti's brother, William Michael, who served as the group's secretary and chronicler. They advocated "truth to nature," meticulous observation, serious and often morally uplifting subjects drawn from the Bible, literature (especially Shakespeare and Keats), and occasionally modern life. Their technical approach involved painting in bright, pure colours over a wet white ground to achieve maximum luminosity, a stark contrast to the darker palettes and broad handling favoured by many established academicians like Sir Joshua Reynolds, whose influence they explicitly rejected.

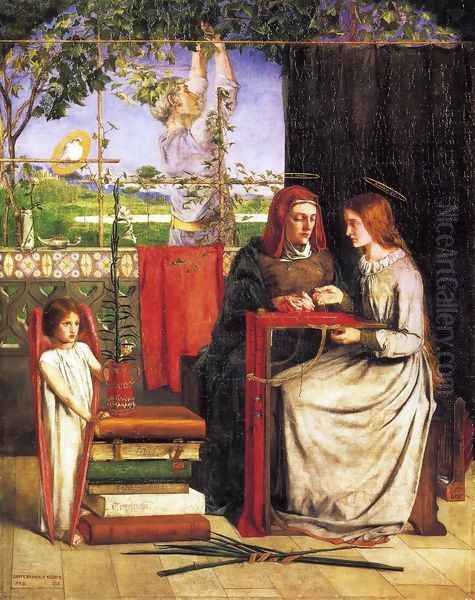

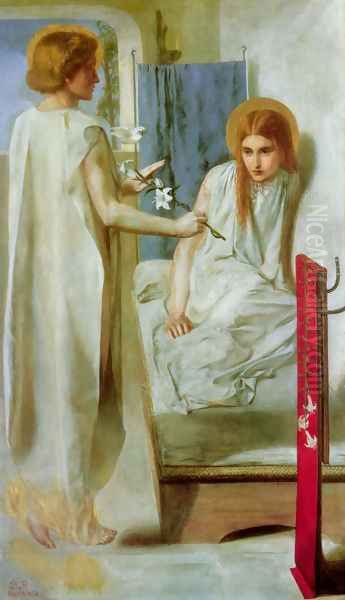

The PRB announced their presence by inscribing their initials on their paintings. Rossetti's first major oil painting exhibited under the PRB banner was The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849). This work, accompanied by two sonnets written by Rossetti himself, exemplified the Brotherhood's ideals with its detailed symbolism, somewhat archaic style, and devotional subject matter. It was relatively well-received. However, his next major PRB work, Ecce Ancilla Domini! (also known as The Annunciation, 1850), provoked harsh criticism for its perceived awkwardness and departure from traditional depictions.

The Pre-Raphaelites faced considerable hostility from the art establishment and critics, notably Charles Dickens, who savaged Millais's Christ in the House of His Parents. Their fortunes began to turn when the influential critic John Ruskin wrote letters to The Times in 1851, defending their aims and artistic merit, albeit with some reservations. Despite Ruskin's support, the intense criticism and internal divergences led to the effective dissolution of the original Brotherhood by 1853, though its influence would continue profoundly.

Artistic Style and Dominant Themes

Rossetti's art is characterized by its sensuousness, medievalism, and profound connection to literature. While initially adhering to the PRB's principle of detailed naturalism, his style evolved towards a more decorative and symbolic manner, particularly after the initial Brotherhood phase. He became less interested in meticulous landscape backgrounds and more focused on the human figure, especially women, depicted with intense psychological presence.

Medieval themes, drawn from Arthurian legends, Dante, and chivalric romance, remained central to his work throughout his life. He saw the medieval past not just as a source of picturesque subjects but as a realm of heightened emotion, spiritual intensity, and symbolic meaning that contrasted sharply with the materialism of Victorian England. His fascination with Dante Alighieri was particularly profound, leading to numerous works inspired by the Vita Nuova and the Divine Comedy, often exploring themes of spiritualized love and tragic loss.

The depiction of women is arguably the most defining feature of Rossetti's art. His female figures are rarely passive objects of beauty; they are often powerful, enigmatic, and psychologically complex. He moved from the ethereal, spiritualized figures of his early work to the more overtly sensuous, often melancholic or brooding women of his later paintings. These iconic images, often referred to as "stunners," with their flowing hair, full lips, and soulful eyes, became hallmarks of his style and significantly influenced later movements like Symbolism and Aestheticism. Artists like William Blake, with his integration of text and image and visionary intensity, also resonated deeply with Rossetti.

A unique aspect of Rossetti's creativity was the intimate dialogue between his painting and poetry. He often created "double works," where a painting and a poem illuminated each other, exploring the same theme or narrative. Sonnets frequently accompanied his paintings, sometimes inscribed directly onto the frame, reinforcing the idea that visual and verbal art could be unified expressions of a single artistic vision. This interdisciplinary approach set him apart from many of his contemporaries.

Major Works: A Visual and Poetic Legacy

Rossetti's oeuvre includes several landmark paintings that define his contribution to British art. The Girlhood of Mary Virgin (1849) remains a key early PRB work, notable for its intricate symbolism (the lily for purity, the dove for the Holy Spirit, the books for virtues) and the depiction of his sister Christina as Mary and his mother Frances as Saint Anne.

Ecce Ancilla Domini! (1850) offered a radically unconventional portrayal of the Annunciation, emphasizing Mary's fear and apprehension rather than pious acceptance. Its stark composition, restricted colour palette (predominantly white, blue, and red), and angular forms drew sharp criticism but showcased Rossetti's willingness to challenge artistic norms.

Perhaps his most famous painting related to his personal life is Beata Beatrix (c. 1864-1870). Created years after the death of his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, it serves as a memorial, fusing her likeness with the image of Dante's beloved Beatrice from the Vita Nuova. The painting is rich in symbolism: the poppy carried by the dove signifies death and Siddal's laudanum overdose, the sundial points to the hour of her passing, and the background depicts Dante and Love in a dreamlike Florence. It is a haunting meditation on love, death, and spiritual transcendence.

Later works often featured specific models who became synonymous with his mature style. Jane Morris, wife of his friend William Morris, became a primary muse, her striking features immortalized in paintings like Proserpine (1874). Here, she embodies the queen of the underworld, holding the fateful pomegranate, trapped in a shadowy realm – a powerful image often interpreted as reflecting the complexities and constraints of their relationship and Victorian womanhood. Astarte Syriaca (1877), also featuring Morris, presents a formidable vision of the Near Eastern love goddess, showcasing Rossetti's late style with its rich colours, decorative intensity, and imposing female presence.

Rossetti also produced significant work in watercolour and illustration. His illustrations for the Moxon edition of Alfred, Lord Tennyson's poems (1857), particularly The Lady of Shalott and Sir Galahad, were highly influential, demonstrating his mastery of intricate design and medieval atmosphere in graphic form. His unfinished painting Found (begun 1854) is notable for tackling a contemporary subject – a "fallen woman" recognized by her former lover – reflecting the PRB's occasional engagement with modern moral themes.

Personal Life: Passion and Tragedy

Rossetti's personal life was marked by intense relationships, profound loss, and inner turmoil. His most significant relationship was with Elizabeth "Lizzie" Siddal, a milliner's assistant whom the Pre-Raphaelites discovered working in a hat shop. She became their iconic model, most famously posing for Millais's Ophelia (lying in a bathtub of water for hours) and becoming Rossetti's exclusive muse, pupil, and lover. Siddal was herself a talented artist and poet, encouraged by Rossetti and Ruskin.

Their relationship was passionate but fraught with difficulties, including Rossetti's infidelities and Siddal's chronic ill health, often treated with laudanum (tincture of opium). After a long and often troubled engagement, they finally married in May 1860. Tragically, Siddal died less than two years later, in February 1862, from an overdose of laudanum, shortly after delivering a stillborn child. Whether the overdose was accidental or intentional remains uncertain.

Devastated by guilt and grief, Rossetti impulsively buried the only complete manuscript of his poems in Siddal's coffin in Highgate Cemetery. This act haunted him. Seven years later, in 1869, encouraged by friends and his opportunistic agent Charles Augustus Howell, Rossetti arranged for the poems to be secretly exhumed. The manuscript was recovered, disinfected, and formed the core of his Poems volume published in 1870. While the publication was a success, the exhumation preyed on Rossetti's mind, contributing to his growing mental instability.

Following Siddal's death, Rossetti's life became increasingly reclusive and eccentric. He developed serious insomnia, which he treated with chloral hydrate, a sedative to which he became dangerously addicted, often mixing it with large quantities of whisky. This addiction, combined with his grief and guilt, led to paranoia, delusions, and a severe mental breakdown in 1872.

His relationships with women remained complex. He had a long and intense, though likely unconsummated, affair with Jane Morris, the wife of his close friend and associate William Morris. Jane became his principal model in the later part of his career, her melancholic beauty dominating his canvases. He also maintained relationships with other models, notably Fanny Cornforth, his housekeeper and mistress, whose voluptuous beauty contrasted with the more ethereal Siddal or enigmatic Morris. His later years were spent largely as a recluse at Tudor House, 16 Cheyne Walk in Chelsea, a large house filled with exotic furniture, objets d'art, and a menagerie of unusual animals, including wombats and peacocks.

Poetry and the "Fleshly School" Controversy

Rossetti's identity as a poet was as crucial to him as his identity as a painter. His first major publication was The Early Italian Poets (1861), a volume of masterful translations from Dante and his predecessors, which significantly contributed to the understanding and appreciation of early Italian literature in Britain. It was later revised and reissued as Dante and his Circle (1874).

The publication of Poems in 1870, containing the exhumed works alongside newer pieces, established his reputation as a major contemporary poet. The volume included sonnets from his sequence The House of Life, love poems, and dramatic narratives. However, its sensuousness and frank exploration of physical and spiritual love provoked controversy.

In October 1871, the critic Robert Buchanan, writing pseudonymously as "Thomas Maitland," launched a scathing attack titled "The Fleshly School of Poetry" in The Contemporary Review. Buchanan accused Rossetti, along with Algernon Charles Swinburne and William Morris, of celebrating base physicality, indecency, and morbid sensuality, singling out poems like Rossetti's "Nuptial Sleep" for condemnation.

Rossetti, deeply wounded by the attack, responded with an essay titled "The Stealthy School of Criticism" (1871). The controversy, however, exacerbated his paranoia and contributed to his withdrawal from public life. Despite this, he continued to write, publishing Ballads and Sonnets in 1881, which included the completed sonnet sequence The House of Life. This sequence, charting the complexities of love, beauty, fate, and death, is now considered one of the major achievements of Victorian poetry, admired for its intricate structure, rich imagery, and emotional depth.

Collaborations, Circles, and Influence

While the formal PRB lasted only a few years, the relationships forged during that time remained significant. Rossetti maintained complex friendships with Hunt and Millais, though their paths diverged artistically and personally. His bond with Ford Madox Brown endured, providing crucial support during difficult times.

Rossetti became a central figure for a second wave of artists associated with Pre-Raphaelitism and the emerging Aesthetic Movement. He was a major inspiration for the younger Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris, whom he met at Oxford in the mid-1850s. Rossetti encouraged their artistic ambitions and collaborated with them on projects like the Oxford Union murals (1857). His influence was pivotal in Morris's shift towards decorative arts, leading to the founding of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. (later Morris & Co.) in 1861, a firm in which Rossetti was initially a partner, dedicated to reviving craftsmanship in furniture, stained glass, textiles, and wallpaper.

John Ruskin remained an important, if sometimes difficult, patron and critic. He supported Rossetti financially and championed his work but also frequently offered unsolicited and sometimes unwelcome advice. Rossetti's circle also included fellow artists like Arthur Hughes, Frederick Sandys, and Simeon Solomon, poets like Swinburne and George Meredith, and patrons like Frederick Leyland, a Liverpool shipping magnate who commissioned several of Rossetti's later works. His relationships with his models – Siddal, Morris, Cornforth, and others like Alexa Wilding – were integral to his artistic practice, blurring the lines between artist, muse, lover, and collaborator. His brother William Michael remained a steadfast supporter and later his diligent editor, while his sister Christina's poetic career developed in parallel, with occasional artistic collaborations between them, such as Dante Gabriel's illustrations for her poem "Goblin Market." Figures like James McNeill Whistler were also part of the broader artistic milieu in Chelsea, representing different facets of the move towards Aestheticism.

Later Career, Declining Health, and Final Years

After the PRB's dissolution and the controversies surrounding his 1870 Poems, Rossetti largely withdrew from public exhibitions, preferring to sell his work directly to a small circle of dedicated patrons. His style continued to evolve, moving further from the detailed realism of early Pre-Raphaelitism. His later paintings are characterized by larger canvases, often focusing on single, half-length female figures presented in rich, decorative settings. The influence of Venetian Renaissance painters, particularly Titian, became more apparent in the opulent colours and textures.

Works from this period, such as Veronica Veronese (1872), La Ghirlandata (1873), and the aforementioned Proserpine and Astarte Syriaca, are powerful, symbolic representations of beauty, love, fate, and sorrow. They often feature his favoured models Jane Morris and Alexa Wilding. While sometimes criticized for repetitive compositions, these later works possess a unique intensity and hypnotic quality, embodying the ideals of the Aesthetic Movement, which prioritized beauty and sensory experience ("Art for Art's Sake").

However, Rossetti's final decade was overshadowed by declining health, exacerbated by his addiction to chloral hydrate and alcohol. He suffered from hydrocele, weakening eyesight, and increasing mental distress, including auditory hallucinations and paranoia. Despite periods of intense productivity, his ability to work became intermittent. Friends, including Ford Madox Brown, William Morris, Thomas Hall Caine, and his brother William Michael, rallied around him, attempting to manage his addictions and care for him.

In late 1881, suffering from kidney failure (then often termed Bright's disease) and partial paralysis following a stroke, Rossetti was moved to a rented bungalow in Birchington-on-Sea, Kent, in the hope that the sea air might aid his recovery. He died there on Easter Sunday, April 9, 1882, at the age of 53. He was buried in the churchyard at Birchington.

Enduring Legacy and Influence

Dante Gabriel Rossetti's impact on the art and literature of the nineteenth century and beyond is undeniable. As a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he played a crucial role in challenging the artistic conventions of his time and revitalizing British painting with a new intensity of colour, detail, and emotional expression.

His work served as a vital bridge between the early Victorian era and the later Aesthetic and Symbolist movements. His emphasis on mood, beauty, symbolism, and the exploration of complex psychological states resonated deeply with artists across Europe. Figures like Edward Burne-Jones carried forward his medievalist and romantic vision, while the sensuousness and decorative qualities of his later work anticipated aspects of Art Nouveau. Artists like Aubrey Beardsley were also indebted to his linear precision and evocative power.

In poetry, The House of Life remains a landmark sonnet sequence, and his translations helped to popularize Dante and early Italian poetry for English-speaking audiences. His "double works," integrating painting and poetry, highlighted the expressive possibilities of combining visual and verbal art, influencing book illustration and design.

Rossetti's life, with its dramatic blend of artistic triumph, passionate love, tragic loss, and personal demons, has continued to capture the public imagination. He remains a figure of fascination, studied not only for his artistic achievements but also for the ways his life and work intersected with the complex cultural currents of the Victorian age – its attitudes towards sexuality, religion, medievalism, and the role of the artist. Though controversial in his time and sometimes criticized since, Dante Gabriel Rossetti's unique fusion of the painterly and the poetic secured his place as a visionary artist whose influence continues to be felt.

Conclusion

Dante Gabriel Rossetti was a towering figure whose dual talents in painting and poetry left an extraordinary legacy. A catalyst for change through the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, he infused British art with a new vibrancy and emotional depth drawn from medieval sources and literary inspiration. His life was one of intense passion, creativity, and personal struggle, elements reflected in the haunting beauty and psychological complexity of his work. From the detailed symbolism of his early paintings to the sensuous icons of his later years, and through the intricate verses of his poetry, Rossetti explored the enduring themes of love, beauty, death, and the spirit. His influence extended far beyond the PRB, shaping the course of the Aesthetic Movement and Symbolism, and ensuring his enduring significance in the history of art and literature.